Riccardo Muti unearths gem in Mahler tribute

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Riccardo Muti, conductor; Gerhard Oppitz, piano. Through Oct. 8 at Orchestra Hall. ***

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Riccardo Muti, conductor; Gerhard Oppitz, piano. Through Oct. 8 at Orchestra Hall. ***

By Nancy Malitz

I have to admit I was not prepared for the stunning surprise in this week’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts conducted by Music Director Riccardo Muti.

I have to admit I was not prepared for the stunning surprise in this week’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts conducted by Music Director Riccardo Muti.

Nestled in a tiny slot, next to last on a program of unusual Italian assortments, came the “Berceuse élégiaque” of Ferruccio Busoni. An exquisite piece of gentle tone painting, it is a cosmic lullaby to a dead loved one, with a sadness to rock your heart.

I don’t know how Busoni managed to achieve this effect of glistening foreverness, but I would love to see the printed music of this score for celesta, gong, harp, strings, a small woodwind contingent and four horns. The beats themselves have nothing of their usual effect. There is no tying them to the ground. On the contrary, it is a weightless work of momentous quiet. No wonder the contemporary composer John Adams loves it. His own “On the Transmigration of Souls,” which has much the same impact, is one of my favorite works by a great composer of our own day.

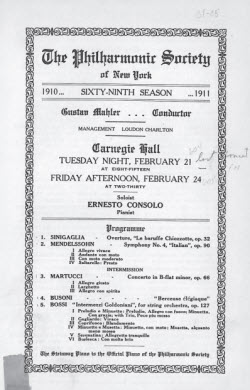

Henceforth I will associate Busoni’s 9-minute work with Mahler’s own passing. Mahler conducted the world premiere of the “Berceuse élégiaque” at what would be the last public performance of his life, with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall on Feb. 21, 1911. It is hard to think of Mahler back then, not yet fully appreciated, himself emaciated and miserable, bundled in blankets on an arduous nine-day passage home to Europe, where he would soon die. I prefer to think that his soul was already afloat in musical rapture, headed for its place in eternity.

Not often does one recommend an entire two and a half hour concert on the basis of nine incredible minutes, but this is one of those times. Busoni, like Schoenberg — and Webern and Berg who came after — was beginning to experiment with sounds untethered from the common do-re-mi of the tonal system. It was far-out stuff that we became accustomed to as the 20th century wore on. There is hardly a movie about outer space or inner mystery that does not make use of this language to some degree.

But the “Berceuse élégiaque” must have made little sense to the audience at Carnegie Hall 100 years ago. Well, to almost no one. Besides Busoni, surely Toscanini, the superstar conductor in the V.I.P box, and the ailing Mahler knew that they were experiencing something strange, wonderful, tantalizing. The future, perhaps?

Mahler never conducted a note after this concert, but of course no one that night in Carnegie Hall realized the program would constitute his farewell to the stage. A fish out of water in New York City, he never enjoyed his rival Toscanini’s popularity. Indeed, few in Mahler’s own time thought of him primarily as a composer. Today, of course, his music is the beating heart of the modern symphonic tradition, his works performed constantly around the globe.

No surprise then that we have lost track of Mahler the practicing musician. We are fortunate that Muti, who is serious about history, followed his intuition in regard to the strange-looking program that was on the docket that fateful night.

Muti decided to program the pieces as they were laid out, in a curious order that today might be best described as attaching two encores right into the plan. A huge, Brahms-like concerto for piano by Giuseppe Martucci, lasting nearly 45 minutes, was followed by the “Berceuse” and then a heady nightcap of four neoclassical dances for strings by Marco Enrico Bossi called “Intermezzi Goldoniani.” Their highpoint was a ravishing “Serenatina” in which the CSO strings surpassed themselves.

Clearly, Muti has an affinity and respect for these pieces. On the concert’s first half was a fresh and witty overture by Leone Sinigaglia that would have sounded great in the pit of a Broadway musical a few decades ago, before synthesizers eradicated the strings. After that came the only piece on the program anyone would recognize today — Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony. You could envision Mahler’s mind at work, deciding that the radiant dispositions of the Mendelssohn and the Bossi would provide a pleasant symmetry.

It was a clever stroke on Muti’s part to program the night as Mahler had done it (shortening only the Bossi a bit.) Had he made a substantial change, we would have missed the chance to experience the way things were. Mahler had a voracious appetite for the new stuff, and he liked the idea of developing a theme for the evening, in this case the sounds of Italy.

But Mahler was no better than anyone else at predicting what music would be considered great 100 years later. He conducted a lot of Wagner and got that right. Martucci, Sinigaglia and Bossi, not so much.

Martucci’s Piano Concerto No. 2 is a substantial work in the Brahms style with a Liszt overlay, and it adds up to a lot of notes to learn. One is grateful to the eminent artist and teacher Gerhard Oppitz for performing the killer piano part, especially considering that he is unlikely to have the opportunity to perform it frequently. He read from the music, which may have robbed him of the chance to connect more directly with the audience, but in any case the work is destined to be tucked back into time’s crowded closet.

Still, it was interesting to hear the Italian Martucci assimilate what he admired in the German and Austrian music of his day — the sense of grandeur, luxurious weight, mighty formal structure.

Meanwhile, the concert offered a delicious mirror image — the Italian-inspired symphony of the German Mendelssohn, in which we sense a thrilled Northern European shedding his galoshes to run barefoot under the warm Italian sun. Muti led an electric performance. The CSO’s winds were quite dazzling in the finale, with its headlong rush for which the onomatopoetic terms “lickety split” and “clickety clack” might have been invented.

Related links:

- Many thanks to John Lambert, founder of CVNC (Classical Voice North Carolina) for suggesting this clip of Toscanini conducting the “Berceuse élégiaque”: Find it at YouTube

- Muti points toward Bruckner and plans that will stretch the CSO: Read the exclusive interview at Chicago On the Aisle

- “Gustav Mahler,” English-language translation of the biography by Jens Malte Fischer: Read the book review

- Chicago On the Aisle overview of the Chicago Symphony’s 2011-12 season: See our concert picks

- From a long life in the opera world, Muti brings Chicago Symphony gifts of drama and poetry: Read the Muti profile

- Chicago Symphony Orchestra: More information about this concert

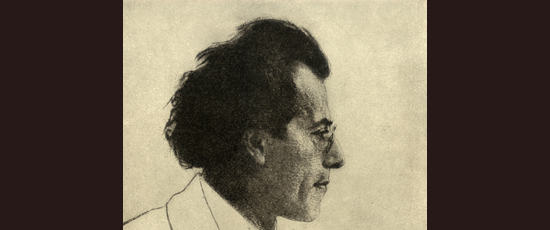

Image captions and credits: Home page: Gustav Mahler sketch by Emil Orlik, 1902; program cover from The Philharmonic Society of New York program, Feb. 21, 1911.

Tags: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Felix Mendelssohn, Ferrucio Busoni, Gerhard Oppitz, Giuseppe Martucci, Gustav Mahler, Leone Sinigaglia, Mahler Centennial, Mahler's last concert, Marco Enrico Bossi, Riccardo Muti

No Comment »

1 Pingbacks »

[…] I had my reservations about a huge Martucci piano concerto that Muti and the CSO performed in 2011, this ambitious song cycle impressed me as a significant historic milestone. Not much of Martucci […]