Williams’ ‘Camino Real’ reshaped as director sets lyricism on a collision course with libido

Review: “Camino Real” by Tennessee Williams, at Goodman Theatre through April 8. ***

Review: “Camino Real” by Tennessee Williams, at Goodman Theatre through April 8. ***

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Tennessee Williams’ obsession with sexuality, in both its most elemental and repressed forms, is well documented. Doubtless reflecting the psychic churn of his own homosexuality, Williams’s plays typically underscore the central roiling role of libido in the human condition. Its specter projects a strong presence, even if it’s veiled beneath his singular patina of lyric prose.

In Spanish director Calixto Bieito’s reimagining of “Camino Real,” Williams’ most abstract play and arguably his most sexually charged, the carnal component is stripped of nearly all its veils and thrust into plain view in a style that forces the line of coarseness. While that choice might be viewed as daring, it carries with it the risk of obscuring the play’s essential philosophical core and masking its poetic nature in a wash of titillation.

In Spanish director Calixto Bieito’s reimagining of “Camino Real,” Williams’ most abstract play and arguably his most sexually charged, the carnal component is stripped of nearly all its veils and thrust into plain view in a style that forces the line of coarseness. While that choice might be viewed as daring, it carries with it the risk of obscuring the play’s essential philosophical core and masking its poetic nature in a wash of titillation.

And so it happens here. The sexual displays are many and, in their variety, graphic. This is doubly to be regretted, first because Bieito seems rather self-consciously to be playing the bad boy and challenging the tolerance of his viewers and, second, because his production otherwise abounds with brilliant flourishes that get at the expressive heart of this curious play.

While sex swirls at the center of “Camino Real,” it is not the play’s sum and substance. The work in its final form was first produced on Broadway in 1953, having evolved from an earlier version called “Ten Blocks on the Camino Real.” The style might be called abstract existential, as it deals with the follies, disappointment, delusions and dead ends of life through a series of loosely connected episodes involving both characters of Williams’ own creation and others from literary history – among them Don Quixote and Lord Byron, Casanova and Camille.

The very title is a paradox: Williams’ Camino Real – Spanish for royal road or, if you like, king’s highway – is anything but regal. It’s the end of the road for nearly everyone in sight, a terminus located in a fictional town that sharply evokes purgatory and could just as well have been invented by Beckett or Sartre. Here, fools come to bluster, the once-beautiful come to mourn their lost youth and hope comes to die. It is a harsh place devoid of pity, where the weak are taunted, the vulnerable exploited. Whether all these people are already dead is open to question. They talk about the place beyond the high boundary wall, which they call terra incognita – perhaps an echo of Hamlet’s “undiscovered country,” death.

Bieito has dropped some of Williams’ characters, combined others and dispensed with the original narrative sequence, which progresses through 16 blocks on the Camino Real. Almost all of these adaptations are to good effect, and it’s easy to imagine Williams finding them so. The reordered scenes possess their own narrative logic, or rather an integrity of ebb and flow since there isn’t exactly a plot. We move from delusion to delusion and through a commingling of delusions; the order matters little.

Bieito has dropped some of Williams’ characters, combined others and dispensed with the original narrative sequence, which progresses through 16 blocks on the Camino Real. Almost all of these adaptations are to good effect, and it’s easy to imagine Williams finding them so. The reordered scenes possess their own narrative logic, or rather an integrity of ebb and flow since there isn’t exactly a plot. We move from delusion to delusion and through a commingling of delusions; the order matters little.

“Camino Real” is a play about the ultimate sadness of life, about its beauty and its brutal reality. All of these things converge in the decaying forms of the great lover Casanova (played with fractured pride by David Darlow) and the once glorious courtesan Marguerite Gautier (or Camille, expressed with radiant pathos by Marilyn Dodds Frank). Darlow’s Casanova is reduced to a sorry, penniless drunk pretending that funds (and his self-esteem) soon will arrive by mail. His liaison with Frank’s fragile Camille cracks when that fading flower betrays him for the rejuvenating thrill of a young man’s attention.

Desperation is the common currency on the Camino Real. Kilroy, a boxer whose better days are behind him (the impressively fit Antwayn Hopper) bounces onto the scene only to be TKO’d with humiliation, and a withered gay baron on the make (suavely turned by André De Shields) gets all he’s looking for and then some. De Shields’ baron revives to stop the show with his belting delivery of “I’ll Put a Spell on You,” as Kilroy (also resurrected, as it were) is about to relieve the gypsy girl Esmeralda (Monica Lopez) of her magically restored virginity. (It’s a renewal-and-loss thing the girl undergoes every month.)

Desperation is the common currency on the Camino Real. Kilroy, a boxer whose better days are behind him (the impressively fit Antwayn Hopper) bounces onto the scene only to be TKO’d with humiliation, and a withered gay baron on the make (suavely turned by André De Shields) gets all he’s looking for and then some. De Shields’ baron revives to stop the show with his belting delivery of “I’ll Put a Spell on You,” as Kilroy (also resurrected, as it were) is about to relieve the gypsy girl Esmeralda (Monica Lopez) of her magically restored virginity. (It’s a renewal-and-loss thing the girl undergoes every month.)

This is some pretty wacky stuff, all presided over by a fellow called Gutman as enforcer, hotel manager, mayor or the devil himself; take your pick. Matt DeCaro is a sardonic Gutman, cold and bureaucratically procedural. One does miss Williams’ street cleaners, the ghoulish characters who remove the corpses each night. Director Bieito has dispensed with them. Ah, well.

He has also sacked Don Quixote, or rather has replaced him with a Tennessee Williams’ stand-in who looks and drawls like the playwright. He’s called the Dreamer (originally a different character in the play but resituated here). This Williams-as-Dreamer (Michael Medeiros) speaks first and last in Bieito’s concept, framing the illusion about to unfold and finally uttering an intimation of redemption. But I fear that grace is lost as Medeiros quaffs from a whisky bottle, declaims, reels, vomits, falls, clambers back to his feet and repeats. It’s a clever idea carried over the top.

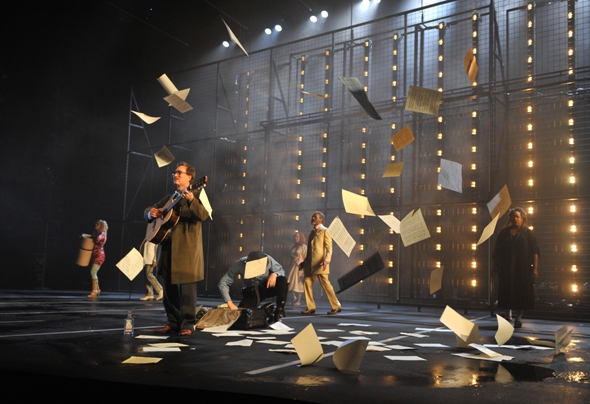

Much of the show’s concentrated power derives from Rebecca Ringst’s creative sets, which evoke both prison and garish entertainment strip. The Camino Real is a perverse place and one senses its decadence here. If only the director had resisted adolescent shock value, and left more to adult imagination.

Related Links:

- A&E Biography of Tennessee Williams: Watch it at YouTube

- Broadway actors discuss playing Tennessee Williams: Jessica Lane, Natasha Richardson and others

- San Francisco Composer Mark Alburger’s multimedia setting of Camino Real: Hear the language as music

- Interview of Tennessee Williams: Read Dotson Rader in the Paris Review

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: Marguerite Gautier, or Camille (Marilyn Dodds Frank), discovers there’s no exit from the Camino Real. Upper right: Antwayn Hopper (left) is Kilroy with Matt DeCaro as Gutman. Lower right: David Darlow as Casanova with Marilyn Dodds Frank as Marguerite Gautier. Left: André De Shields portrays Baron de Charlus. Below: Behind the scenes at the Goodman with the creative team and its actors. Lower: The Gypsy (Carolyn Ann Hoerdemann) announces Fiesta. At gottom: The Dreamer (Michael Medeiros) as balladeer. (Photos by Liz Lauren)

Tags: "Camino Real", Andre De Shields, Antwayn Hopper, Calixto Bieito, David Darlow, Goodman Theatre, Marilyn Dodds Frank, Matt DeCaro, Rebecca Ringst, Tennessee Williams