‘Mr. Rickey’ imagines a prelude to history, before Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers

Review: “Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting” by Ed Schmidt, at Lookingglass Theatre through Feb. 19. ***

Review: “Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting” by Ed Schmidt, at Lookingglass Theatre through Feb. 19. ***

By Lawrence B. Johnson

It was never going to be easy, not even for an athlete as gifted as Jackie Robinson, to break major league baseball’s color line. It was no snap, either, for Branch Rickey, the president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, to force that issue on segregated America in 1947 and cast Robinson as the first black player in baseball’s Big Show.

How Robinson and Rickey decided to go for it, with a little help from some high-profile friends, is the essence of Ed Schmidt’s 1989 play “Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting,” a hypothetical fantasy now on intriguing display at Lookingglass Theatre.

How Robinson and Rickey decided to go for it, with a little help from some high-profile friends, is the essence of Ed Schmidt’s 1989 play “Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting,” a hypothetical fantasy now on intriguing display at Lookingglass Theatre.

Actually, the narrow plank of history in Schmidt’s drama is little more than a springboard, an authentic situation that allows the playwright’s imagination to soar toward a clever final splash. Indeed, “Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting” brings to mind Steve Allen’s 1970s television series “Meeting of the Minds.” Historical characters convene to hash out a matter of great sociological consequence. The fact that no such meeting ever took place is beside the point. The imagined colloquy is the thing. I can’t say it is compelling stuff, but it is evocative, mostly plausible and abrasive enough to be credible.

In Schmidt’s scenario, Branch Rickey has made up his mind to take the plunge. He will promote Jackie Robinson from the Dodgers’ Montreal farm team and install him with the parent club on opening day of the 1947 season. But Rickey also has decided to hedge his bet: He has invited three black celebrities – boxer Joe Louis, dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and actor-singer Paul Robeson – to meet with him and the star of his venture in hope of soliciting their support. Well, the course of social change never did run smooth, and Rickey gets much more than he bargained for. He finds himself embroiled in a heated debate.

Or more accurately, Rickey and everybody else in the room are hurled into battle with the notoriously (and historically) pugnacious freedom fighter Robeson. Eloquent, keenly intelligent and willful, Robeson confronts both Rickey and the black men with this question: Just one black player – after all these years of exclusion, just one? What about all the rest, including many who are better ball players than Jack Robinson? Where’s the progress in that?

Robeson, played with grand presence and disarming conviction by James Vincent Meredith, swiftly becomes the debate’s gravitational center. Meredith, who cuts a statuesque figure that commands respect, captures the bitter irony and sarcasm of a man who believes his apparently successful black brethren have always sold out to The Man. That the issue is baseball seems almost incidental to Robeson, who presses the “workers of the world” mantra. Step by step nothing: He wants Revolution!

Yet despite the brow-beating they all take from Robeson, each of the other black men has his pride, and each passes through a personal arc of shock, indignation and consummation. Anthony Fleming III’s Joe Louis nearly steals the spotlight from Meredith’s Robeson, and with far fewer words. Fleming catches the Brown Bomber’s coiled power, and more than once unleashes just enough of it to put everyone else on guard. The boxer is also impatient, eager to sign off on Rickey’s plan and get on with his day. Fleming’s restiveness hones the production’s tension to an edge you can feel.

Yet despite the brow-beating they all take from Robeson, each of the other black men has his pride, and each passes through a personal arc of shock, indignation and consummation. Anthony Fleming III’s Joe Louis nearly steals the spotlight from Meredith’s Robeson, and with far fewer words. Fleming catches the Brown Bomber’s coiled power, and more than once unleashes just enough of it to put everyone else on guard. The boxer is also impatient, eager to sign off on Rickey’s plan and get on with his day. Fleming’s restiveness hones the production’s tension to an edge you can feel.

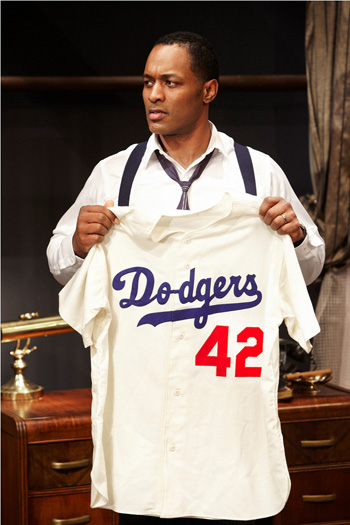

As Bojangles, Ernest Perry Jr. shows us an aging hoofer who takes life as it comes and doesn’t think too deeply, lest reality take the bloom from his mellowness. At the opposite extreme, Javon Johnson’s Jackie Robinson is a serious young man of few words, conditioned by Rickey to smile, avoid confrontation and keep turning the other cheek. So devoutly does Johnson’s aspirant keep his peace that when he finally opens up, the force of that eruption quiets even the loquacious Robeson.

Rickey is the catalyst in all this, both manager and umpire of his own game, and Larry Neumann Jr.’s wiry form and insistent voice lend the old pro a conflicted aura of faith and anxiety. He’s constantly checking his pocket watch, as if it were the hourglass of opportunity in which he sees the sand draining away.

There’s also another character in this hotel room, a bellboy – perhaps the black everyman, or rather the black man of a brighter future, for this young fellow is just 17 years old. His Dickensian name is Clancy Hope, to whom Kevin Douglas brings an irresistible mix of buoyancy and bedazzlement. Clancy is a Yankees fan. But he could get over that.

“Mr. Rickey” is a talkative play, and yet director J. Nicole Brooks adroitly sustains the illusion of action and movement. That it’s also an almost mystical moment in America’s social evolution is pointed up by designer Sibyl Wickersheimer’s hotel room set, its green carpet framed like some field of dreams by the iconic lines that extend past first base and third, a place where one black man won equal footing on common ground.

Related links:

- Location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Baseball, the Color Line and Jackie Robinson: Peruse six decades of history at the Library of Congress

- Hear Paul Robeson’s extraordinary voice: Go to the audio gallery with pictures at Robeson Foundation website

- Bill “Bojangles” Robinson’s is in the Tap Dance Hall of Fame: Visit him at the American Tap Dance Foundation

Photo captions and credits: Home page, top and upper right: Javon Johnson as Jackie Robinson. Middle right: Anthony Fleming III as Joe Louis. Below: James Vincent Meredith, left, as Paul Robeson; Ernest Perry Jr., seated, as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Larry Neumann Jr., right, as Mr. Rickey, debate Rickey’s proposition while Anthony Fleming III ( as Joe Louis) and Javon Johnson (as Jackie Robinson) look on.

Tags: Anthony Fleming III, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Ed Schmidt, Ernest Perry Jr., J. Nicole Brooks, Jackie Robinson, James Vincent Meredith, Javon Johnson, Joe Louis, Kevin Douglas, Larry Neumann Jr., Lookingglass Theatre, Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting, Paul Robeson