Chailly lifts his quick baton, and Beethoven’s symphonies emerge from the veil of tradition

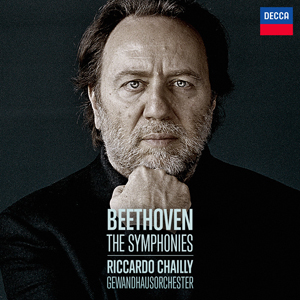

CD Review: Riccardo Chailly leads the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in a complete cycle of the nine symphonies plus concert overtures. Decca, 5 discs with hardbound booklet. *****

CD Review: Riccardo Chailly leads the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in a complete cycle of the nine symphonies plus concert overtures. Decca, 5 discs with hardbound booklet. *****

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Conductor Riccardo Chailly’s new recording of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, may finally be the document that changes the way we think of these seminal works – and the way the next generation of conductors approaches them. Chailly faithfully adheres to Beethoven’s controversial metronome markings, which are generally quite fast, but at the same time he illuminates and animates the symphonies from within and his virtuoso orchestra tosses them off with an élan that’s thrilling in a thousand ways.

Beethoven harbored a special fondness for his Fourth Symphony, and he declared the Eighth Symphony a finer work than its birth twin the Seventh. We might smile at such paternal indulgence – we who confidently accept from long tradition that Beethoven composed just four symphonies of real import: the odd-numbered ones, omitting of course the First and perhaps allowing a limited exception for the Sixth.

Thus, largely, has the world regarded the “nine” symphonies for more than a century and a half. No less astute a critic than Robert Schumann helped to engrave that perspective. It was he who characterized Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony as “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants,” those being the grand “Eroica” and the mighty Fifth. Schumann, like Wagner after him and certainly Mahler, saw in Beethoven the great symphonic dramatist, the exemplary Romantic sculptor of edifices in sound. Never mind that fewer than half of his symphonies lend themselves to that interpretation. Tradition has made it so.

Yet it’s also true that for the last several decades a dedicated string of apostates have argued against this view of Beethoven as thunder-clapper. These conductors have observed a more Classical take on his works, with less histrionic musical rhetoric and more respect for the brisk tempos Beethoven specified in his metronome markings. Mostly, however, their counter-argument has centered on faster tempos – sometimes with period instruments trotted out for added authenticity – and mostly they haven’t been very convincing. Depth gives way to speed.

Yet it’s also true that for the last several decades a dedicated string of apostates have argued against this view of Beethoven as thunder-clapper. These conductors have observed a more Classical take on his works, with less histrionic musical rhetoric and more respect for the brisk tempos Beethoven specified in his metronome markings. Mostly, however, their counter-argument has centered on faster tempos – sometimes with period instruments trotted out for added authenticity – and mostly they haven’t been very convincing. Depth gives way to speed.

But with Chailly’s new Beethoven cycle we finally get the full, persuasive picture of how Beethoven might have imagined all nine of his symphonies — how indeed they may have sounded under the agile, sympathetic and knowing direction of Felix Mendelssohn when he was chief conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Chailly’s Beethoven effectively wipes the board clean. It isn’t just fresh or novel; it is revelatory.

Scintillating as the First and Second Symphonies are at Chailly’s brisk tempos – Beethoven’s tempos – these performances also make several key interpretative points that will mark this entire series. It isn’t the ticking metronome that drives the music, but rather fluid rhyhms that seem to originate from deep below the melodic surface. In other words, Chailly’s pulse is never metronomic, never rigid. What we get is a kind of shimmering liquid sculpture.

The Third Symphony presents the first test case in its – dare I say monumental – slow movement, which Beethoven designated as Marcia funebre. Rather than the solemn, even dragging tempo we’ve come to associate with this music, Chailly moves it right along. It is a funeral march, but with the emphasis on march, and there is a heady tension in it that catches you up and doesn’t let go. To sample Chailly’s propulsive opening of the first movement, listen here.

Likewise, in the Fifth Symphony’s mystery-laden scherzo, Chailly’s finely gauged, albeit quick, tempo is enough to raise the hair on your neck. And here, as everywhere, the Gewandhaus Orchestra negotiates the rapidly passing terrain with breath-taking aplomb. The low strings’ blitz through the scherzo’s rollicking midsection is one of the most electrifying episodes of the entire cycle. The opening of the Fifth Symphony springs to life. Listen here.

Likewise, in the Fifth Symphony’s mystery-laden scherzo, Chailly’s finely gauged, albeit quick, tempo is enough to raise the hair on your neck. And here, as everywhere, the Gewandhaus Orchestra negotiates the rapidly passing terrain with breath-taking aplomb. The low strings’ blitz through the scherzo’s rollicking midsection is one of the most electrifying episodes of the entire cycle. The opening of the Fifth Symphony springs to life. Listen here.

Perhaps as much as anything, it’s the violins’ lightness of touch combined with the sheer elegance of the woodwind playing – an unflagging impression that makes one simply forget about tempo – that renders these performances so infectious and satisfying. Take the Allegretto of the Seventh Symphony, another movement often fraught with Wagnerian hyperbole: Chailly almost bounds through it, yet so buoyant is the playing that the fleeting tempo seems only natural, even the only one possible. I’m not edging into “definitive” here, but Chailly’s command of Beethoven’s metronome markings created for me a mind-blowing sequence of “aha” moments.

The slow movement of the Ninth Symphony, as sublime a patch as Beethoven ever penned, is clearly faster in Chailly’s hands than one has come to expect. Yet the feeling is not one of haste but rather of uplifting radiance. The impulsive scherzo fairly flies, but on sinuous wings: Listen here. And the grand cantata that caps the Ninth, Beethoven’s beloved setting of Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” possesses an ethereal sparkle born of the Gewandhaus Choir. End to end, this is a Ninth more joyous than ponderous.

All this still does not address Beethoven’s fair-haired children, the Fourth and Eighth Symphonies and with them a larger point. It isn’t so much that Chailly alters the character of those two “even-numbered” symphonies, but rather in lifting the weight of overweening drama from the rest he shows the continuity of authorship of the whole series. We no longer see Beethoven alternating between Important Works and mere bagatelles. The odd-numbered symphonies now belong with their siblings, masterpieces one and all. And that includes the Sixth, the ever-debated “Pastoral,” whose zephyrs Chailly and company capture with the merry zeal of children wielding butterfly nets.

The five-disc set also includes most of Beethoven’s overtures, among them virile accounts of “Coriolan,” “Egmont” and “Leonore No. 3.” The CD slipcases are bound in a handsome, hardcover booklet that also provides a telling essay on Chailly’s view of Beethoven and the romanticizing tradition he has endeavored to strip away. He has taken us back to the Beethoven of Mendelssohn, and it is a midwinter night’s dream.

Related Links:

- Chailly’s Beethoven cycle is available for purchase online: Go to ArkivMusic.com

- The cycle also can be dowloaded: Go to iTunes

- Listen to excerpts free: Go to Soundcloud

- Works by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendessohn, Schumann, Wagner and Brahms received their world premieres in Leipzig: Learn more

- Beethoven and Leipzig: Discover more about the composer’s relationship with the city

- Chailly became Gewandhauskapellmeister (principal conductor) in 2005: Read Chailly’s bio

Photos and credits: Home page: Conductor Riccardo Chailly (Decca). Top: Beethoven symphonies box cover. Upper left: Metronome in action. Lower left: Beethoven statue by Max Kinger. Below: Leipzig Gewandhaus at night (Photo by Jaime Silva)

Tags: Beethoven, Decca, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, metronome, Riccardo Chailly

How does Chailly’s cycle compare to the Gardiner DG cycle? I could tell from your post that you weren’t too happy with the past results of period instrument conductors. However I know that the Gardiner cycle is just fine. I’ve noticed that at times Gardiner is more spacious than Chailly or Hogwood and I’ve also observed that he has adopted fluid and flexible tempi, for instance during the slow movement of the Ninth.

How does Chailly’s cycle compare to the Gardiner DG cycle? I could tell from your post that you weren’t too happy with the past results of period instrument conductors. However I know that the Gardiner cycle is just fine. I’ve noticed that at times Gardiner is more spacious than Chailly or Hogwood and I’ve also observed that he has adopted fluid and flexible tempi, for instance during the slow movement of the Ninth.