‘Hamlet’ at Chicago Shakespeare: In honoring Bard’s language, an actor hones ambivalence

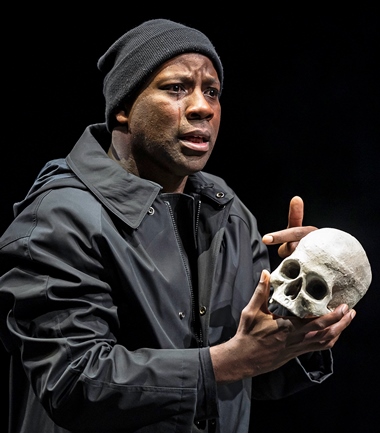

Ophelia (Rachel Nicks) is distressed and confused to find Hamlet (Maurice Jones) turning away from her. (Production photos by Liz Lauren)

Review: “Hamlet” by William Shakespeare, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater through June 9. ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

The much that is good about Chicago Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” is very good indeed, starting with Maurice Jones’ rigorously thought-through and yet convincingly spontaneous performance as the melancholy Prince of Denmark. But unevenness among the rest of the principal roles takes a toll on this enterprise helmed by the company’s artistic director, Barbara Gaines.

Would that the whole troupe exhibited the sense of weight and import of Shakespeare’s language that seems quite natural to Jones from the outset. Hamlet is the soul of ambivalence: to do or not to do – to strike down his murderous uncle Claudius and thus avenge his dead father or simply wallow in his grief, rage and paralyzing distress. Hamlet is, as it were, intensely ambivalent. He is obsessed with his uncertainty. It takes possession of him; it is all he thinks about. Jones resonates to Hamlet’s muddle, his equivocation and indecision.

It is through measured language that Jones conveys the torment of a perceptive and astonished young man who has literally seen – and spoken with – his father’s ghost. Not exactly metered language, but thoughts propelled by impulse, at once articulate and inflected by swirling circumstance, this sea of troubles. “Nothing,” observes Hamlet, “is either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Jones is a thinking Hamlet, struggling to come to grips with his bizarre situation, trying to find his way through it, shuddering at the awfulness of his filial duty – and flummoxed by his inability to take action.

Time and again, Jones’ charged soliloquies remind us that the distraught prince is not reciting; he is searching his soul, agonizing, confessing. Hamlet affects madness – he tells his close friend Horatio of that intent – to give himself space and distance to watch and assess. And in his surging emotion, Jones deftly blurs the line between Hamlet’s dissembling and his actual grip on reality. When this Hamlet gets in the face of sweet Ophelia, whom he adores, and commands her to betake herself to a nunnery lest she spawn more corrupt creatures like his “mother-aunt” Gertrude or his “uncle-father” Claudius, his fury is palpable and true.

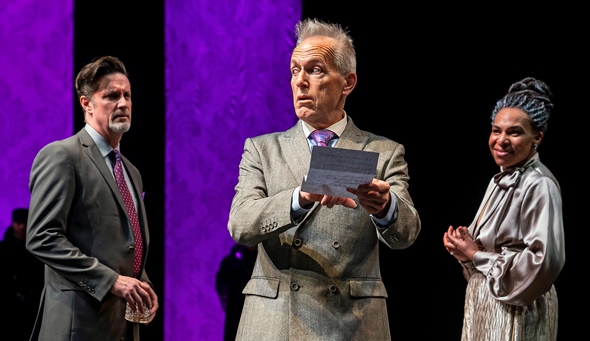

Pompous, foolish old Polonius (Larry Yando) shares a revealing letter with King Claudius (Tim Decker) and Queen Gertrude (Karen Aldridge).

And when Jones’ careening prince confronts his mother in her bedchamber, his physical assault on her is so fierce as to suggest a deflection of the hurt he cannot inflict on his incestuous uncle-father. Gertrude’s part is played out largely on the periphery, but in this explosive pivotal scene, she has her moment, and Karen Aldridge stokes it with fearsome heat. Did Gertrude conspire with Claudius to kill Hamlet’s father, or is she quite unaware that he was murdered? (A fatal sting is the official palace story.) In the face of Jones’ rant, Aldridge’s perplexed – then frightened – queen evokes her own unsure ground between wedded consort of Claudius and alarmed loving mother of this agitated, rambling, incomprehensible son.

It’s during Hamltet’s confrontation with his mother, that the meddling, foolish old Polonius, Ophelia’s father, meets his mortal end at the tip of Hamlet’s rapier. Too bad to see him go when he’s so deliciously embodied in Larry Yando’s unhurried, pompous and pointedly tedious portrayal. Much like Hamlet’s “To be or not to be,” Polonius’ counsel on manly comportment to his departing son Laertes is a speech that practically invites the audience to join in chorus – and all but defies the speaker to find something fresh in it. Yando rises to that challenge with a slyly paced, deadly earnest diatribe that draws laughter as Paul Deo, Jr.’s dutiful Laertes scribbles his father’s wisdom in a notebook even as he mouths along to the oft-repeated words.

The duel with rapiers between Laertes (Paul Deo, Jr., left) and Hamlet (Maurice Jones) is electrifying in its speed and intricacy.

That, to my mind, was Deo’s single flourish in a performance that generally seemed constrained, headlong and wanting texture. But kudos to Deo and Jones alike for their fateful contest with rapiers – by a wide margin the most electrifying duel I’ve ever witnessed on a stage, the fast, intricate and harrowing choreography of Matt Hawkins.

More problematic are Tim Decker’s overdriven, monotonal Claudius and Rachel Nicks’ rather shallow Ophelia. I found Decker’s nefarious King to be essentially devoid of nuance as he charged about the stage, speaking most of his lines in the same color, pitch and tempo. Ophelia’s big moment is her mad scene, her mind unhinged by the coincidence of Hamlet’s cold rejection and her father’s death. Nicks’ monologue felt more like an actress hitting her marks, with due punctuation, than the transported speech of an innocent girl broken by circumstance.

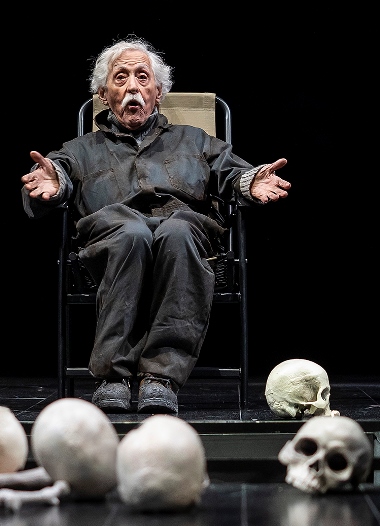

The imperishable Mike Nussbaum is a delight as the gravedigger, a worldly philosopher if ever there was one, and Sean Allan Krill offers a suitably mystified but faithful Horatio, Hamlet’s one true friend. The production’s large ensemble is well provided in the play’s minor roles.

Designer Scott Davis’ nearly bare stage allows the language to carry the play, which gains décor in the attractive and diverse costumes of Susan E. Mickey.

In streamlining “Hamlet,” the longest of Shakespeare’s plays, Gaines has made judicious trims that leave the narrative logic intact. A bit of a jolt comes when Hamlet, en route to England, pauses to view a passing army and speaks with its commander about the small patch of ground that will be the dubious prize of the ensuing battle. This leads Hamlet to reflect, in his final soliloquy, on the quality and purpose of a man – on his own worth in light of his failure to act against Claudius.

But that great speech is omitted. Hamlet bids the captain good day, turns on his heel and exits.

Though it’s a complex and probing self-examination, even if perhaps redundant at this point in the play, I would happily have indulged the extra few minutes to hear Jones’ deliver it. His adroit Hamlet is one to be savored in full measure: clever enough to catch the conscience of the King and reason enough to catch this show.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

1 Pingbacks »