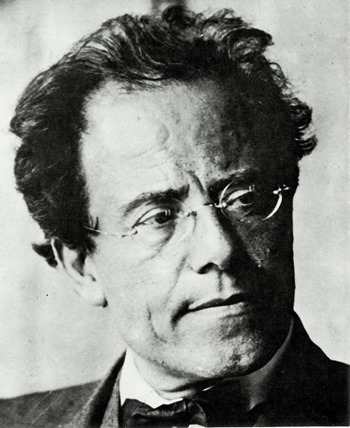

Salonen leads Chicago Symphony on Mahler’s Ninth Symphony voyage of life, transcendence

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, at Orchestra Hall. Repeats May 22.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Somewhere along the mountainous range of peak moments in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s recent seasons stands the performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony led by Esa-Pekka Salonen on May 17 at Orchestra Hall. It was memorable in a degree commensurate with the monumentality of the work itself, and the Ninth Symphony vies only with the song-symphony “Das Lied von der Erde” as Mahler’s absolute masterwork.

Those two symphonies have some significant things in common beyond their shared epic scale. They come one upon the other near the end of the composer’s life. “Das Lied von der Erde” occupied Mahler from 1908 into 1909, and the Symphony No. 9 in D was written immediately after in 1909. Mahler, who died May 18, 1911, never heard either work. His protégé Bruno Walter conducted both world premieres, “Das Lied” later that year and the Ninth Symphony in 1912.

Those two symphonies have some significant things in common beyond their shared epic scale. They come one upon the other near the end of the composer’s life. “Das Lied von der Erde” occupied Mahler from 1908 into 1909, and the Symphony No. 9 in D was written immediately after in 1909. Mahler, who died May 18, 1911, never heard either work. His protégé Bruno Walter conducted both world premieres, “Das Lied” later that year and the Ninth Symphony in 1912.

Rather like existential twins, both symphonies ultimately confront mortality – but only after immersing themselves in the joys and sorrows of earthly life. Though the Ninth Symphony may lack the specificity of a text, it might be said literally to take up – at the very outset – the contemplation of eternity articulated in “Der Abschied,” the closing song of “Das Lied.” Something like the falling musical figure of “Ewig” (Forever), at the end of “Das Lied,” engenders the Ninth Symphony, and the ethereal fade-out at the close of the Ninth essentially mirrors the expiration of “Das Lied.” One might even view the beginning and end of the Ninth Symphony as dust to dust.

Or one might say – and this was very much the essential beauty of Salonen’s account – that Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is rounded with a sleep. That rounding, still-voiced and transcendent, also reflected both the technical finesse and the expressive sensibility of the Chicago Symphony. First and last, Salonen sought and received a sound of exquisite expansiveness, a cosmic genesis and then a leave-taking that over-arched the comprehension of time.

The Ninth is one of just four Mahler symphonies that conform to the four-movement classical model. But the sequence of tempos departs from convention: a broad Andante is followed by a careening country dance and a riotous, urbane burlesque before the symphony ends in a sweeping Adagio. And the work’s temporal frame is tremendous: It runs more than 85 minutes. In Salonen’s hands, however, this vast musical process took on an aura of concision and inevitability that suggested the efficiency and directness of Beethoven.

The Ninth is one of just four Mahler symphonies that conform to the four-movement classical model. But the sequence of tempos departs from convention: a broad Andante is followed by a careening country dance and a riotous, urbane burlesque before the symphony ends in a sweeping Adagio. And the work’s temporal frame is tremendous: It runs more than 85 minutes. In Salonen’s hands, however, this vast musical process took on an aura of concision and inevitability that suggested the efficiency and directness of Beethoven.

Perhaps the highest accolade that might be paid to Salonen and company was the remarkable silence in the hall. The audience was rapt from the start and rapturous at the finish.

The splendor of this performance was established at once, with an opening movement that showcased luxurious string playing, the precision and warmth of a large complement of winds, and gorgeous French horns complemented by fiery brasses – and all woven by Salonen with clear perspective on Mahler’s pervasive counterpoint.

If sober reflection informs the grandeur of that first chapter, it quickly gives way to characteristic flights of Mahlerian irony, first in a rollicking ländler that simultaneously celebrates and mocks transitory life. Here, and in the ensuing Rondo-Burlesque with its commedia dell’arte quirks and surprises, Salonen adroitly spun rhythmic inflection and dynamic shifts to underscore Mahler’s view of the world as an unpredictable and by no means reassuring place.

The finale, marked “Very slow and reserved,” puts all that – the mad panoply of life – behind and turns our eyes evenly and confidently to the horizon. It is music of majestic spirituality, and Salonen allowed its wings to spread and its radiance to engulf the hall. This was the Chicago Symphony with its banners unfurled, its pace “very slow,” its gestures “reserved,” its effect transformative.

Related Links:

- Performance and ticket info: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Esa-Pekka Salonen