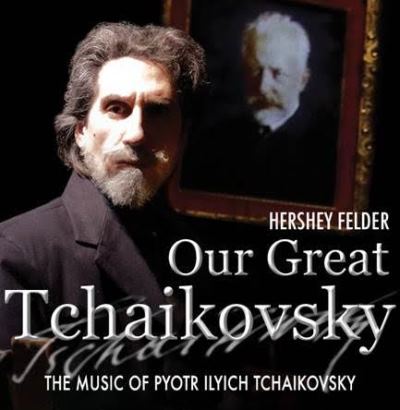

Hershey Felder, face of many musical giants, takes on the genius and pain of Tchaikovsky

Review: “Our Great Tchaikovsky,” written and performed by Hershey Felder; presented at Steppenwolf Theatre through May 13. ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Give pianist-actor Hershey Felder credit. He has managed to crawl inside the skin of characters as diverse as Bernstein and Beethoven and Irving Berlin, and to give them plausible life. His latest solo turn, as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, is about to wind up a brief run in the upstairs space at Steppenwolf Theatre.

Musically, this portrait is as authoritative and satisfying as any of its predecessors; but as a dramatic, balanced and illuminating exploration of Tchaikovsky, man and artist, Felder’s breathing sculpture left me with the impression of a work not yet finished.

Felder pursues two parallel themes: the essential, defining importance of music and musical composition in Tchaikovsky’s life, and his lifelong anxiety over the socially intolerable fact that he was homosexual. Indeed, Felder is probably justified in making the composer’s torment over his attraction to young men no less prominent in the narrative than the creation of his First Piano Concerto or the “Pathétique” Symphony or the “Nutcracker” ballet.

Felder pursues two parallel themes: the essential, defining importance of music and musical composition in Tchaikovsky’s life, and his lifelong anxiety over the socially intolerable fact that he was homosexual. Indeed, Felder is probably justified in making the composer’s torment over his attraction to young men no less prominent in the narrative than the creation of his First Piano Concerto or the “Pathétique” Symphony or the “Nutcracker” ballet.

The play is called “Our Great Tchaikovsky,” the proud claim of mother Russia – or of the Russian government, as Felder explains in a prologue in his own voice and appearance. Holding a letter he purportedly received a couple of years ago from some Russian agency, Felder says it’s an invitation to present his portrayal of Tchaikovsky in Moscow – where homosexuality is forbidden by law and one does not speak of the beloved composer’s sexual orientation the way it is generally accepted elsewhere in the world. The actor says he doesn’t know how to answer the letter. We’re about to see why he ultimately declined.

Seating himself at the piano, Felder then morphs into Tchaikovsky, adopting a sort of Russian accent and commencing the story of his youth, his discovery of music, his consignment to law school by his family and his eventual revolt – and joyful commitment to studies in piano and composition. He would have been in heaven on earth, he recalls, except for this nagging distraction, this powerful impulse to which he cannot give a name and which he dared not reveal.

Seating himself at the piano, Felder then morphs into Tchaikovsky, adopting a sort of Russian accent and commencing the story of his youth, his discovery of music, his consignment to law school by his family and his eventual revolt – and joyful commitment to studies in piano and composition. He would have been in heaven on earth, he recalls, except for this nagging distraction, this powerful impulse to which he cannot give a name and which he dared not reveal.

But the impulse is real and exhilarating, and it draws him to beautiful young men. It turns out Tchaikovsky’s brother Modest shares his proclivity. Meanwhile, a teacher observes that Tchaikovsky isn’t married. A young man with aspirations should have a wife. Go, marry. And so Tchaikovsky does, disastrously. He soon flees. But the wife, from whom he is never divorced, basically blackmails him, tapping the increasingly famous composer whenever she needs an infusion of cash.

Out of the blue, he receives a letter from a wealthy admirer, Nadezhda von Meck, a widow who has decided to provide the composer with a generous allowance that will enable him to concentrate on his art. But they are neither to meet nor speak, ever. Felder recounts this remarkable history with credible amazement and rhetorical flair, accompanying himself throughout at the piano. That was, for me, the rub: Felder plays too much, his back to the audience, the music too often unidentified, its selection unexplained. Like so much wallpaper.

He does provide context for the big works, and indeed goes through a witty sequence as the young composer first presenting the now-adored Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor to his teacher. Tchaikovsky says that since there’s no orchestra, he will sing the orchestra part, which he does while he plays the piano line. When that fails to make an impression, he plays both the solo and orchestra parts simultaneously at the piano – and finally the real orchestral music wells up, pre-recorded, as Felder/Tchaikovsky plays on through this splendid music.

He does provide context for the big works, and indeed goes through a witty sequence as the young composer first presenting the now-adored Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor to his teacher. Tchaikovsky says that since there’s no orchestra, he will sing the orchestra part, which he does while he plays the piano line. When that fails to make an impression, he plays both the solo and orchestra parts simultaneously at the piano – and finally the real orchestral music wells up, pre-recorded, as Felder/Tchaikovsky plays on through this splendid music.

The occasional use of pre-recorded orchestral music nicely complements the selective use of video projected on a rear scrim. But Felder’s choice to turn a good deal of his playing into background music works against the narrative. And the story-telling gets a bit heavy-handed with forced comedy when Tchaikovsky recalls writing the “1812 Overture,” which he dismisses with a grimace as not music at all – and expresses annoyance that it became the thing for which he was best known.

Disbelief becomes hard to suspend when Felder occasionally drops out of character to fast-forward through his story in his own voice and persona. In the end, Felder must deal with Tchaikovsky’s mysterious death in 1893, at age 53, just eight days after the premiere of his last symphony, the “Pathétique.” Was he murdered for his homosexuality? Was he ordered to take his own life or face deportation to Siberia? Did he condemn himself by seducing a young man – maybe a boy – related to the czar?

As Felder observes in his own voice, we probably never will know what happened. Just before the lights go out, the actor undergoes a change, a makeover, his back to the audience. In this new guise, he turns to ponder the piano, standing in silence. That altered aspect was arresting, really quite disarming. I wondered, why now? Why only now?

Tags: Hershey Felder, Modeste Tchaikovsky, Nadezhda von Meck, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky