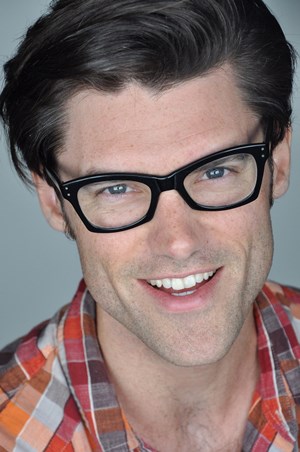

Role Playing: Zachary Stevenson elevated his Buddy Holly from hiccups to the rockin’ truth

Interview: Actor who plays Buddy Holly with American Blues Theatre recalls a tough learning curve to master Holly’s infectious vocal style, stage presence.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Zachary Stevenson slips into the persona of Buddy Holly like the early rocker’s doppelgänger in American Blues Theatre’s extended run of the musical “Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story,” by Alan Janes. Stevenson says he feels that identity – now. But back when he first landed the part, more than a decade and some 12 productions ago in Toronto, it was a different story.

“I thought I might be in over my head,” Stevenson says. “The songs sound simple, but once I realized the amount of work that would be required vocally, I knew it was going to be tough. It took a lot of woodshedding, vocally and on the guitar.” Obviously, the effort has paid dividends several times over. But back at the start, the actor says, “I never imagined this would be a recurring role.”

“I thought I might be in over my head,” Stevenson says. “The songs sound simple, but once I realized the amount of work that would be required vocally, I knew it was going to be tough. It took a lot of woodshedding, vocally and on the guitar.” Obviously, the effort has paid dividends several times over. But back at the start, the actor says, “I never imagined this would be a recurring role.”

Buddy Holly – clean cut, tall, lanky, bespectacled and a bit awkward – burst out of Lubbock, Tex., and onto the national scene in 1957. His meteoric career lasted only about 18 months before he died in a plane crash in Iowa on Feb. 3, 1959, at age 22 while on tour. In that short time, he produced a prodigious stream of hits. And his distinctive singing style, marked by a sort of hiccup delivery, together with impulsive guitar riffs that roughly mirrored that mannerism, would influence virtually every rock artist after him, from the Beatles and Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones.

Stevenson, whose Holly-esque vocal gestures and even physical inflections are honed to a natural ease, showed up at the first audition as a creature from an entirely different world.

“I was like any other actor answering a casting call,” he says. “I’d been doing ‘Hair’ in Toronto. I had huge sideburns and long hair. I knew a little bit about Buddy Holly, and I played ‘Everyday’ and ‘It’s So Easy.’ I guess they saw through the sideburns.

“But I’ve always loved rock and roll. Otherwise, I don’t think I could ever have made this work. I’ve got to feel that fire internally every time I’m on stage – to let the music excite me the way it excited Buddy. He was a very talented, passionate, driven guy.”

Stevenson admits that getting into Buddy Holly’s skin – and soul – involved a progression from what he calls “cookie-cutter” copying to breaking down Holly’s style and bit by bit internalizing the elements.

“I notated lyrics and tried to find my own little accents,” he says. “I studied where the hiccups were, how he chopped up certain words and broke them down, like at the beginning of ‘Rave On’ – that ‘A-weh-a-heh-a-hell, the little things you say and do…’ And Buddy plays guitar like he sings. His voice ranges from high nasal to mimicking Elvis with a deep sound. There’s all kinds of variety in the way he attacks notes and rhythms.

“It was all very technical at first. Before it felt natural to me, it felt very unnatural – kind of like learning a new instrument. But over time, I feel like I’ve come to know the freedom he felt, to have fun with it. The experience is different from one performance to the next. It doesn’t look, sound or feel the same. That wouldn’t work.”

What was natural from the start and critically helpful, Stevenson says, was the similarity between his vocal range and Holly’s.

“It was a little like paint-by-numbers at the start while I got a sense of how it should feel in my own muscles,” he says. “It’s incredible how at a certain point muscle memory kicks in. I don’t think about it anymore. My voice is now at a place where Buddy’s songs just feel right to sing. It’s funny, and sad in a way: I’ve had more opportunity to sing these songs than he did.”

Along with the vocal challenge came the task of capturing the physical Buddy Holly in performance. That’s not a small factor. The few clips available reveal that when Holly was on stage, the music seemed to ripple down the length of his body.

Along with the vocal challenge came the task of capturing the physical Buddy Holly in performance. That’s not a small factor. The few clips available reveal that when Holly was on stage, the music seemed to ripple down the length of his body.

“Since there’s so little footage out there, you have to extrapolate Buddy’s sense of physicality and expand on it quite a bit,” Stevenson says. “You read that Buddy Holly and the Crickets (his back-up players on bass and drums) were a lot more unhinged on stage than you might infer from the rather contained Buddy in the TV clips.

“You see his right leg keeping time. He’s a red-blooded young man with some sexual energy, but he’s not the sexual force that Elvis was. Buddy was sort of nerdy, but he embraced who he was – not traditionally good looking, a kind of awkward guy who had to wear glasses. Sort of like Roy Orbison.”

In no other venue where Stevenson has assumed the form of Buddy Holly has his work come under such close-up inspection as it does every night in the intimacy of the American Blues production at Stage 773.

“When I first saw the space,” the actor recalls, “I thought, Oh, my God, how are you going to fit ‘Buddy’ in here? But it’s been really cool. The immediacy of the audience has kept me from getting lost in old habits, to stay laser focused. There’s no room to get distracted. And if someone in the audience shouts something out, I’m likely to respond. That’s real. I love that.”

Confronting such intimate reality was the core message Stevenson got from director Lili-Anne Brown, he says.

“She reminded me to go for the truth, and she got me to think about Buddy a bit differently. He’s on the brink of something huge. Nobody else knows it yet. He’s constantly being told he’s wrong, but in his heart he knows he’s right. Buddy’s like the Mark Zuckerberg of rock and roll. He knows he has an element of genius.”

Related Links:

Review of “Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story”: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle

More Role Playing interviews:

- K.K. Moggie, as Scottish queen Mary Stuart, got to a royal heart layer by layer

- Kathleen Ruhl went for laughs, but resisted harsh character that gets them

- Kate Fry’s vivid Emily Dickinson sprang from poet’s fine-tuned, evocative verse

- Joel Reitsma drew moral profit from banker-captor clash of ‘Invisible Hand’

- Lawrence Grimm found Lincoln first in pages of history, then within himself

- Cristina Panfilio spreads wings she didn’t know she had as midsummer Puck

- Tyla Abercrumbie was set to run little ‘Hot Links’ café, but why was she there?

- AnJi White, as Catherine Parr, learned to keep her wits – to keep her head

- Adam Bitterman, unlikely florist in ‘Seedbed,’ dug deep to create a rare bloom

- Danny McCarthy, pushing broom in ‘The Flick,’ finds vital pulse in long silences

- Mierka Girten, actor with MS, knows wound behind her character’s scars

- Sandra Marquez, as Clytemnestra, sees an exceptional woman in the Greek queen

- Brian Parry says he summoned courage before wit as George in ‘Virginia Woolf’

- Tracy Michelle Arnold debunks madness as force that drives Blanche DuBois

- Christopher Donahue, as Ahab, finds sea’s depth in sadness of a vengeful soul

- Lance Baker embodies ennui, despair of fugitive Jews in ‘Diary of Anne Frank’

- Francis Guinan embraces conflict of father who fled from grim truth in ‘The Herd’

- Sophia Menendian reached back (but not far) as plucky Armenian refugee of 15

- Lindsey Gavel’s distressed Masha, in ‘Three Sisters,’ began with a touch of cheer

- Hollis Resnik felt personal bond with zealous, skeptical scholar in ‘Good Book’

- A.C. Smith is ready undertaker, lord of diner world in ‘Two Trains Running’

- Lia D. Mortensen’s intense portrait of a mentally failing scientist holds mirror to life

- Siobhan Redmond sees re-formed Lady Macbeth as valiant queen in ‘Dunsinane’

- Eileen Niccolai harnessed a storm of emotions to create spark in Williams’ Serafina

- Steve Haggard, aiming at reality, strikes raw core of grieving man in ‘Martyr’

- Shannon Cochran found partners aplenty in sardonic, twice-told ‘Dance of Death’

- Natalie West scaled back comedy to nail laughs, touch hearts in ‘Mud Blue Sky’

- Dave Belden, actor and violinist, adjusted pitch for ‘Charles Ives Take Me Home’

- Joseph Wiens starts at full throttle to convey alienation of ‘Look Back in Anger’

- Shane Kenyon touches charm and hurt of lovable loser in Steep’s ‘If There Is’

- Ramón Camín sees working class values in Arthur Miller’s tragic Eddie Carbone

- Hillary Marren’s charming, rapping witch in ‘Woods’ shapred by hard work, free play

- Mary Beth Fisher embraces both hope, despair of social worker in ‘Luna Gale’

- Brad Armacost switched brothers to do blind, boozy character in ‘The Seafarer’

- Karen Woditsch shapes vowels, flings arms to perfect portrait of Julia Child

- Ora Jones had to find her way into Katherine’s frayed world in ‘Henry VIII’

- Kareem Bandealy tapped roots, hit books for form warlord in ‘Blood and Gifts’

- Eva Barr explored two personas of Alzheimer’s victim to find center of ‘Alice’

- Darrell W. Cox sees theater’s core in closed-off teacher of ‘Burning Boy’

- Chaon Cross turned Court stage into a romper room finding answers in ‘Proof’

- Dion Johnstone turned outsider Antony to bloody purpose in ‘Julius Caesar’

- Noir films gave Justine Turner model for shadowy dame in ‘Dreadful Night’

- Anish Jethmalani plumbs agony of good man battling demons in ‘Bengal Tiger’

- Gary Perez channels his Harlem youth as quiet, unflinching Julio in ‘The Hat’

- Kamal Angelo Bolden sharpened dramatic combinations to play ‘The Opponent’

- In wheelchair, Jacqueline Grandt explores paralysis of neglect in ‘Broken Glass’

- James Ridge thrives in cold skin of Shakespeare’s smiling serpent, Richard III

- Stephen Ouimette brews an Irish tippler with a glassful of illusions in ‘Iceman’

- Ian Barford revels in the wiliness of an ambivalent rebel in Doctorow’s ‘March’

- Chuck Spencer flashes a badge of moral courage in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Price’

- Rebecca Finnegan finds lyrical heart of a lonely woman in ‘A Catered Affair’

- Bill Norris pulled the seedy bum in ‘The Caretaker” from a place within himself

- Diane D’Aquila creates a twice regal portrait as lover and monarch in ‘Elizabeth Rex’

- Dean Evans, in clown costume, enters the darkness of ‘Burning Bluebeard’

- Dan Waller wields a personal brush as uneasy genius of ‘Pitmen Painters’

- City boy Michael Stegall ropes wild cowboy in Raven Theatre’s ‘Bus Stop‘

- Brent Barrett is glad he joined ‘Follies’ as that womanizing, empty cad Ben

- Sadieh Rifai zips among seven characters in one-woman “Amish Project”

- Kirsten Fitzgerald inhabits sorrow, surfs the laughs in ‘Clybourne Park’

- Janet Ulrich Brooks portrays a Russian arms negotiator in ‘A Walk in the Woods’

Tags: Alan Janes., American Blues Theatre, Lili-Anne Brown, Mark Zuckerberg, Zachary Stevenson