‘Faust’ at Lyric Opera: The vibe is American, accent clearly French, and a stylish devil rules

Review: “Faust” by Charles Gounod, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago through March 21. ★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

The story of Faust’s bad bet with the Devil is so entrenched in popular culture that it hardly needs retelling, although audiences have become a tad blasé regarding Charles Gounod’s opera on the subject.

Prior to the mid-20th century, Paris and London were in the habit of trotting out “Faust” annually. New York was so enthusiastic about the French romantic opera, and saw it so often, that a prominent critic in a fit of weary badinage dubbed the Met the “sacred Faustspielhaus.”

After the Second World War demand for “Faust” waned, and the opera was coaxed into a far more leisurely rotation. The Lyric Opera of Chicago has scheduled it seven times at roughly eight-year intervals, most recently in 2009, the last three times in Frank Corsaro productions.

Thus primed for an entirely new take on “Faust,” the Lyric now has one of strong visual aesthetic and modern psychological insight, conceived by the visionary California artist John Frame and brought to the stage by a young production team led by director Kevin Newbury and set-costume designer Vita Tzykun.

Thus primed for an entirely new take on “Faust,” the Lyric now has one of strong visual aesthetic and modern psychological insight, conceived by the visionary California artist John Frame and brought to the stage by a young production team led by director Kevin Newbury and set-costume designer Vita Tzykun.

The impressive cast under the baton of French conductor Emmanuel Villaume stars tenor Benjamin Bernheim – in his American debut – as the doomed Faust, soprano Ailyn Pérez as the seduced and abandoned Marguerite and bass-baritone Christian Van Horn as Hell’s provocative emissary, bent on their destruction. And although the conductor and the impressive star tenor are French, this “Faust” has a bracing American vibe and cinematic feel. Director Newbury’s previous productions have centered on protagonists such as Walt Disney and Steve Jobs, and on dramatic thrillers derived from American novels such as “Bel Canto” (about a terrorist hijacking, premiered at the Lyric in 2015) and “The Manchurian Candidate.”

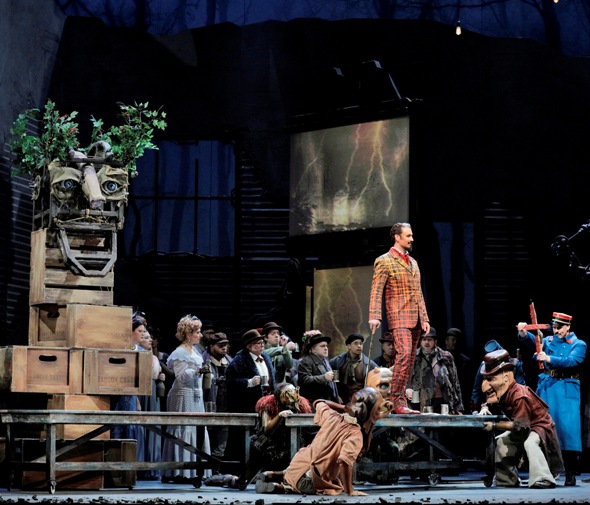

If, on opening night, the stage business left some moments difficult to track and sending the mind to wander, Frame’s remarkable, unsettling sculptures had real pull. They resembled action figures from a dark time, with almost primitive power – notably in their unusual, haunting, even disembodied, eyes. My bet is that the production will speak well to the generation of theater-savvy Chicagoans who might have resisted the opera’s 19th-century views on love out of wedlock, sibling hierarchy, the glory of war, even the nature of the devil himself. Marguerite’s particular vulnerability and the nature of Faust’s one-way ticket to hell both get significant, credible tweaks, with a dash of the macabre.

A “Faust” production can tip the dramatic focus toward any of the three principal characters: the disillusioned Faust who summons the devil in despair; the innocent Marguerite who is contemptuously pawned; or Méphistophélès himself. This production makes much of the evil angel played by bass-baritone Christian Van Horn. Imposing in voice and height alike in his role debut as a stylish seducer of souls, Van Horn’s debonair Méphistophélès seemed delighted by his job’s nefarious challenges.

(An alum of the Lyric’s Ryan Center training program, Van Horn is to create the devil in a different opera, Boito’s “Mefistofele” at the Met come November.) The singer was at his best in Méphistophélès’s cruelly taunting third act serenade: Punctuating his mockery with laughter, he cooed about the dangers of kissing without a ring on the finger for the benefit of the already pregnant, utterly bereft Marguerite.

(An alum of the Lyric’s Ryan Center training program, Van Horn is to create the devil in a different opera, Boito’s “Mefistofele” at the Met come November.) The singer was at his best in Méphistophélès’s cruelly taunting third act serenade: Punctuating his mockery with laughter, he cooed about the dangers of kissing without a ring on the finger for the benefit of the already pregnant, utterly bereft Marguerite.

Méphistophélès travels the Lyric stage with four gnome-like minions, unique to Frame’s artistic conceit, who act on the devils’ commands. They guide the arms of the unknowing Marguerite, spy on Faust, cause general chaos, whatever the moment requires. These able non-singing actors, who wore giant head masks of Frame’s devising and demonstrated admirable body discipline, went from prolonged still poses to quick, bot-like actions, as if malignantly remote-controlled.

Méphistophélès travels the Lyric stage with four gnome-like minions, unique to Frame’s artistic conceit, who act on the devils’ commands. They guide the arms of the unknowing Marguerite, spy on Faust, cause general chaos, whatever the moment requires. These able non-singing actors, who wore giant head masks of Frame’s devising and demonstrated admirable body discipline, went from prolonged still poses to quick, bot-like actions, as if malignantly remote-controlled.

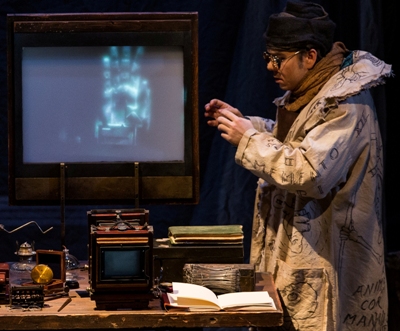

But who is Méphistophélès? That he might be an extension of Faust’s own will is sometimes suggested in productions, successfully so in this one. With Faust as sculptor, rather than scholar, his hands are obsessive seekers. Faust begins to carve at the height of his desperation, and it is Satan’s face that slowly emerges.

The action leading up to that moment begins in the overture, as the light comes up on the interior of Faust’s atelier. Objects of his making lie around. But the artist is now old. His hands seem to be in revolt. We see him stumbling about, trying to mount the scaffolding to attend to his giant sculpture of a man searching skyward through a scope of many lenses. Faust looks pathetically weak for the work, yet still fiercely driven. He glares at his hands, now useless claws.

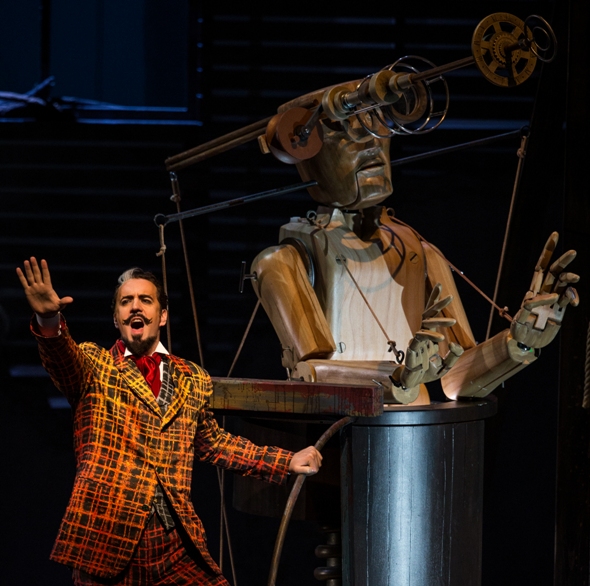

The block of wood remaining on Faust’s table is like the life insurance policy of a man drowning in debt, cashed in for a last-ditch trip to the high-stakes gambling table in Vegas. The chance that this desperate artist’s last bet will surpass the limits of his enfeebled self is several dozen digits to the right of 00.0. Yet Faust begins to carve. The wooden face takes on clarity, and through sleight of projection, rather like the Commendatore’s statue coming to life in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” there he is, Méphistophélès, looking dapper in red plaid, in the flesh, ready to fiddle with the odds.

The block of wood remaining on Faust’s table is like the life insurance policy of a man drowning in debt, cashed in for a last-ditch trip to the high-stakes gambling table in Vegas. The chance that this desperate artist’s last bet will surpass the limits of his enfeebled self is several dozen digits to the right of 00.0. Yet Faust begins to carve. The wooden face takes on clarity, and through sleight of projection, rather like the Commendatore’s statue coming to life in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” there he is, Méphistophélès, looking dapper in red plaid, in the flesh, ready to fiddle with the odds.

Faust, stupefied, stares at his suddenly young hands. If Bernheim, who was all one could wish for in his stirring American debut, stared at those transformed palms of his too long – well into the next scene – he is forgiven.

This fine artist has an elegant voice of warmth and brilliance, perfect for the role of Faust in his renewed vigor. It flowers easily at the top, glorious and confident. The love song, “Salut! demeure chaste et pure,” sung to Marguerite, in whom Faust sees a divine soul and a beauty of nature, is a classic moment in the opera, and Bernheim nailed it handsomely. The truth in the sincerity of Bernheim’s Faust belied the pernicious circumstance of this wooing; she is a poverty-stricken cripple, and he, under the devil’s spell, is about to defile her, a terrible idea, but in the ironic frozen moment of his aria, it seemed inevitably right.

This fine artist has an elegant voice of warmth and brilliance, perfect for the role of Faust in his renewed vigor. It flowers easily at the top, glorious and confident. The love song, “Salut! demeure chaste et pure,” sung to Marguerite, in whom Faust sees a divine soul and a beauty of nature, is a classic moment in the opera, and Bernheim nailed it handsomely. The truth in the sincerity of Bernheim’s Faust belied the pernicious circumstance of this wooing; she is a poverty-stricken cripple, and he, under the devil’s spell, is about to defile her, a terrible idea, but in the ironic frozen moment of his aria, it seemed inevitably right.

The hobbling of soprano Ailyn Pérez’s Marguerite with a crutch began to make sense dramatically as the girl’s Jewel Song unfolded: In it, Méphistophélès leaves a chest of treasures to dazzle and corrupt the girl into a tryst with Faust. In this production, as she begins to try on the baubles and succumb to their power, Pérez’s Marguerite is set purposefully a-twirl with the help of the minions, and she suddenly has no need for the wooden brace. Her ecstatic scene was as charming as Marguerite’s escape from damnation was shining at the opera’s end; it opened out brilliantly with the aid of the Lyric Opera orchestra and celestial choir. Villaume drew impressive work from Lyric’s large forces throughout.

Promising new faces included baritone Edward Parks as Valentin, the proud soldier who curses his fallen sister for straying. Jill Grove was genuinely funny as Marguerite’s protective neighbor Marthe, who forgets all about the girl once Méphistophélès turns on the charm. And Annie Rosen, who also came up through the Ryan program, was enchanting in her trouser role as the adoring Siébel, always in character, her touching arias little exquisitely set gems.

Promising new faces included baritone Edward Parks as Valentin, the proud soldier who curses his fallen sister for straying. Jill Grove was genuinely funny as Marguerite’s protective neighbor Marthe, who forgets all about the girl once Méphistophélès turns on the charm. And Annie Rosen, who also came up through the Ryan program, was enchanting in her trouser role as the adoring Siébel, always in character, her touching arias little exquisitely set gems.

Related Links:

- Performance location, and dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

- Artist John Frame’s Faust film: View it Vimeo.com

- Design team transforms Lyric Opera’s ‘Faust’ into multisensory experience: Read it at the Chicago Sun-Times

Tags: Ailyn Pérez, Annie Rosen, Benjamin Bernheim, Christian Van Horn, David Adam Moore, Duane Schuler, Edward Parks, Faust, Gounod, Jill Grove, John Frame, Kevin Newbury, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Vita Tzykun

No Comment »

2 Pingbacks »

[…] https://chicagoontheaisle.com/2018/03/08/faust-at-lyric-opera-the-vibe-is-american-accent-clearly-fr… […]