Muti’s mighty Chicago forces wind up Carnegie campaign with impressive reprise of Prokofiev

Report: Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus concluded their visit to Carnegie Hall with an idiosyncratic finale and an extended coda courtesy of the weather.

By Nancy Malitz

NEW YORK — Culminating in a Carnegie Hall concert of Russian rarities on Super Bowl Sunday, in the wake of a travel-hampering blizzard on the eastern seaboard and another underway in Chicago, Riccardo Muti’s weekend visit to New York City with his Chicago Symphony Orchestra and its Chorus of 144 voices might have seemed ill-timed.

Yet there was a wild and welcome counter-intuitive energy to the idiosyncratic final program that Muti brought to his trilogy of concerts at the 57th Street temple of music, which concluded with Alexander Scriabin’s Symphony No. 1 (1899-1901) and Sergei Prokofiev’s 1939 cantata “Alexander Nevsky,” adapted from music for the film by Sergei Eisenstein. The mighty pairing was the same that Muti and the CSO had offered in Chicago Jan. 22-24, and the sight at Carnegie was indeed that of a small army assembled, with the chorus and orchestra sharing the stage from beginning to end.

The impression that lingers is not so much of a forceful front as it is of a rich and layered realm, shaped with elegance and an Italian generosity of spirit by a conductor who is in his heart a story-teller, and an operatic one at that.

The impression that lingers is not so much of a forceful front as it is of a rich and layered realm, shaped with elegance and an Italian generosity of spirit by a conductor who is in his heart a story-teller, and an operatic one at that.

At 73, Muti embarks next season upon his second five-year tenure with the CSO. The pre-eminent Italian maestro appears to be taking the path that many artists take in their maturity — delving deeper into rich veins mined earlier in his career.

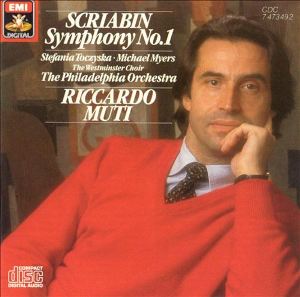

It was the Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter who first recommended the Scriabin symphonies to Muti when he was still young and unknown internationally. Muti would undertake them all beginning in the late 1980s, during his tenure as music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, producing then-revelatory recordings that exulted in the lyricism of Scriabin’s Romantic roots and also found modernistic tendencies that, in Muti’s minority view, bore kinship with Mahler.

But when it comes to the obscure First Symphony of Scriabin, written as the 20th century turned, critics have tended to hear simplistic repetition and naïve poetry. The six-part work concludes with a paean for chorus, the text penned by Scriabin himself, foursquare in its strophic repeats that praise Art and the “endless ocean of emotion” that it breeds.

But when it comes to the obscure First Symphony of Scriabin, written as the 20th century turned, critics have tended to hear simplistic repetition and naïve poetry. The six-part work concludes with a paean for chorus, the text penned by Scriabin himself, foursquare in its strophic repeats that praise Art and the “endless ocean of emotion” that it breeds.

Muti is an effective cure for what ails the listener in such cases. As he does with early Tchaikovsky and much of the Italian bel canto opera literature, including and especially early Verdi, Muti sees repetition as essential fuel that feeds off the smallest changes to spark an increasingly expectant audience. With two Russian powerhouses to sing Scriabin’s solo verses in the gathering momentum — St. Petersburg native tenor Sergey Skorokhodov and Moscow born mezzo-soprano Alisa Kolosova — the buildup was dizzying indeed. As for the five short movements that led up to Scriabin’s choral finale — including a particularly expansive leggiero centerpiece and a quite funky, balletic scherzo — there was Muti’s usual theatrical logic, luxuriously unfolding.

In pairing Scriabin’s First Symphony with Prokofiev’s “Nevsky” cantata, Muti explored the earlier work not so much in the context of European contemporary counterparts such as Schoenberg’s “Verklärte Nacht,” Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 and Debussy’s “Nocturnes,” but rather in light of the common musical ancestry of Prokofiev and Scriabin, rooted in ancient Russian soil.

In this he makes a good case. At the heart of Prokofiev’s “Alexander Nevsky” is the “Battle on the Ice,” which builds relentlessly through repetition to depict a 13th-century death struggle between the Russians and invading Teutonic hordes, who drown in waves of sound as the ice gives way. But it follows with mighty strophes of timeless weight and bearing — a lament for a young Russian woman (the stirring Kolosova) who vows to choose a husband from among the hacked and bloodied, and the patriotic cry of the Russians against all invaders, a soaring expression that Muti and the CSO honored with the dignity of “Va, pensiero.”

Carnegie Hall audiences hear Muti and his Chicago forces in a different context than do the audiences at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. Muti’s Windy City concerts constitute only a third of the orchestra’s annual mainstage events, but in New York City these days, Muti and the CSO are synonymous. His performances with the CSO and Chorus of Verdi’s “Otello” in concert (2011) and Orff’s “Carmina Burana” (2012) received high critical praise.

Carnegie Hall audiences hear Muti and his Chicago forces in a different context than do the audiences at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. Muti’s Windy City concerts constitute only a third of the orchestra’s annual mainstage events, but in New York City these days, Muti and the CSO are synonymous. His performances with the CSO and Chorus of Verdi’s “Otello” in concert (2011) and Orff’s “Carmina Burana” (2012) received high critical praise.

That said, New York has a much longer memory of Muti than Chicago does. Carnegie was the site of his American breakthrough in 1975 with the Philadelphia Orchestra, as a young conductor under Eugene Ormandy’s wing. Muti returned in regular pilgrimages with the Philadelphia Orchestra through 1992, many of them as music director. He also brought Verdi’s Requiem with La Scala’s orchestra and chorus in 1992, and he was a regular visitor with the vaunted Vienna Philharmonic through 2010. (See more about these years in a detailed profile by Chicago writer Dennis Polkow.)

Carnegie’s history with the Chicago Symphony was especially strong in the Solti and Barenboim eras, when the CSO visited pretty much every other year, coming out well in comparisons with other orchestras esteemed among the world’s best. Recent visits have been less frequent, and next season’s headliners do not include the Chicago Symphony, a falloff that seemed to vex Muti at the season-announcing press conference in January.

Rather the top featured ensembles next season will include the Berlin Philharmonic with Simon Rattle (multiple all-Beethoven concerts), the Vienna Philharmonic with Valery Gergiev (excerpts from “Götterdämmerung” and Russian favorites), and the Boston Symphony with Andris Nelsons (Strauss’ “Elektra” in concert.) Muti’s concert version of Verdi’s “Falstaff,” scheduled for April 2016, might have been a marvelous addition to this line-up. Muti and the CSO are nothing if not competitive, and the organization is right to tout the strengths of its robust professional chorus, which has flourished under Muti’s nurturing.

Yet this may not be the optimal moment to raise the issue of more frequent touring with the folks who have to pay for such aspirations. Late Sunday, with Chicago’s weather closing in and flights being canceled left and right, the prospect of additional hotel costs loomed in what turned out to be an expensive storm. A small group had been scheduled to fly back to Chicago Sunday night, but that flight was postponed until Monday, according to Rachelle Roe, the CSO’s director of public relations. And the blizzard was just getting started: “Then the Monday flights were cancelled for all groups. All are expected back today!” Roe reported at mid-day Tuesday. “But these are the quirks of touring, especially in the winter. You cannot count on the weather. It’s always something that can happen.”

Yet this may not be the optimal moment to raise the issue of more frequent touring with the folks who have to pay for such aspirations. Late Sunday, with Chicago’s weather closing in and flights being canceled left and right, the prospect of additional hotel costs loomed in what turned out to be an expensive storm. A small group had been scheduled to fly back to Chicago Sunday night, but that flight was postponed until Monday, according to Rachelle Roe, the CSO’s director of public relations. And the blizzard was just getting started: “Then the Monday flights were cancelled for all groups. All are expected back today!” Roe reported at mid-day Tuesday. “But these are the quirks of touring, especially in the winter. You cannot count on the weather. It’s always something that can happen.”

In fairness it does not take a couple hundred musicians onstage including a chorus for the CSO to make a memorable impression. On Jan. 31 at Carnegie, at the mid-point of the orchestra’s residency, Yefim Bronfman joined Muti and purely orchestral forces to reprise his recent Chicago offering of the Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto, a collaboration as plush and effortless-seeming as it was warm, lyrical and wise. The event concluded with Schumann’s “Rhenish” Symphony in a lovely, laid-back take that had the orchestra sounding as silken and sumptuously Old World as I have ever heard it.

Related Links:

- In first of three concerts at the iconic venue, CSO and Riccardo Muti display their elite stamp: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

- Muti and the CSO announce details of the 2015-16 season: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

No Comment »

1 Pingbacks »

[…] Muti and the CSO took Prokofiev’s “Alexander Nevsky” to Carnegie Hall in 2015: Read about it at Chicago On the Aisle […]