New York Aisle: Met’s balanced ‘Klinghoffer’ revealed depth of Adams’ controversial opera

Analysis: In the historical line of other once-contested masterpieces, “The Death of Klinghoffer” is already a different experience than it was at its Brussels premiere 23 years ago.

By Nancy Malitz

NEW YORK — The raw controversy that surrounds John Adams’ 1991 opera “The Death of Klinghoffer” will outlast this generation, so caught are we still in the toxic swirl of religion and blood, guns and oil, with new and dreadful headlines daily. But to sit in the audience at the Metropolitan Opera, where a richly inflected production of “Klinghoffer” unfolded this fall, was to experience the opera itself coming into focus.

There have been 25 mountings of “Klinghoffer” throughout the world, counting TV film, concert, semi- and fully-staged projects, according to a listing in the Metropolitan Opera’s Playbill. In its deeply resonating threads of emotional complexity, ancient grievance, horror and catharsis, the Met’s straightforward traversal of the story is the most persuasive to date.

It’s disarming how Adams’ directly expressive score, as championed by conductor David Robertson, illuminates the layered meaning of poet Alice Goodman’s probing libretto. Her words, often unjustly dismissed in my view, offer the highest reward to those who are patient and persistent, but they also challenge the director to further clarify rather than obscure.

It’s disarming how Adams’ directly expressive score, as championed by conductor David Robertson, illuminates the layered meaning of poet Alice Goodman’s probing libretto. Her words, often unjustly dismissed in my view, offer the highest reward to those who are patient and persistent, but they also challenge the director to further clarify rather than obscure.

While room remains for sharpening that focus, the balance that director Tom Morris (“War Horse”) achieved between brutal narrative and probing reflection seemed right in all essentials. He first tried his production in 2012 at the English National Opera, and the time-tested images that linger are stark, stunning and dignified. As for the Met’s splendid choristers – who have become a fluidly physical ensemble of fine individual actors due, at least in part, to the continuing demands of HD – they offered heartfelt portrayals of humanity in all its individual striving and confusion, hopelessness and fury.

Some have accused the Met of wretched timing, in the wake of new waves of violence that make it painful for many to reflect upon the hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro, and the murder of elderly Leon Klinghoffer, the disabled Jewish American from New Jersey who was shot and tossed into the ocean by terrorists in 1985. The young guns, focused on Palestinian liberation, had come aboard with plans to create havoc with a suicide mission once the luxury cruiser docked in Israel. That goal was thwarted when they were discovered while still at sea, and thus they gruesomely improvised.

But the accusation rests on a misunderstanding of the opera’s recent history and the nature of opera’s long planning cycles in general. To plan a new production at the Met is to work many years ahead because of the complex logistics involved, often in cooperation with other companies. Confidence in the idea that the time was right for “Klinghoffer” possibly arose because the opera was being presented throughout the world with increasing frequency and success in the early 21st century. There have been 18 major mountings since 2001.

But the accusation rests on a misunderstanding of the opera’s recent history and the nature of opera’s long planning cycles in general. To plan a new production at the Met is to work many years ahead because of the complex logistics involved, often in cooperation with other companies. Confidence in the idea that the time was right for “Klinghoffer” possibly arose because the opera was being presented throughout the world with increasing frequency and success in the early 21st century. There have been 18 major mountings since 2001.

Adams’ own work has continued to be associated with the most painful and complex of subjects. The New York Philharmonic was among the commissioners of his response to the attacks of 9/11, a piece for orchestra, chorus, children’s choir and pre-recorded tape called “On the Transmigration of Souls.” Adams termed it a “memory space” and it went on to win the Pulitzer in 2003. His 2005 opera “Doctor Atomic,” directed by Adams’ longtime collaborator Peter Sellars, which premiered at the San Francisco Opera, deals with Robert Oppenheimer’s creation and test of the first atomic bomb.

And the curtain has just gone up on the world stage premiere of another Adams-Sellars collaboration, “The Gospel According to the Other Mary,” at the English National Opera. It focuses on the final weeks of Jesus’s life, from the viewpoint of Mary Magdalene. Writing in the British daily “The Guardian” on Nov. 20, Sellars once again defended Adams and “Klinghoffer,” citing opera’s roots in Greek dramas, “which were about the most difficult and dangerous topics, recognizing that we can only face them if we face them as one. Opera uses music, poetry, dance and visual art to draw the widest range of people together, people who are wired in different ways. It then puts them inside rather than outside the experience. Looking at something does not mean you’re endorsing it.”

And the curtain has just gone up on the world stage premiere of another Adams-Sellars collaboration, “The Gospel According to the Other Mary,” at the English National Opera. It focuses on the final weeks of Jesus’s life, from the viewpoint of Mary Magdalene. Writing in the British daily “The Guardian” on Nov. 20, Sellars once again defended Adams and “Klinghoffer,” citing opera’s roots in Greek dramas, “which were about the most difficult and dangerous topics, recognizing that we can only face them if we face them as one. Opera uses music, poetry, dance and visual art to draw the widest range of people together, people who are wired in different ways. It then puts them inside rather than outside the experience. Looking at something does not mean you’re endorsing it.”

At this point there is little doubt that “The Death of Klinghoffer” will work its way into the standard repertoire, along with once resisted or censored works by Mozart, Donizetti, Beethoven, Strauss, Berg, Shostakovich and especially Verdi that are part of the accepted canon. New York City, with its large Jewish population, the living memory of 9/11 and recent terrorist actions along the Eastern seaboard, will remain a special case for caution.

Yet the most timely, difficult issues have long been vigorously tolerated by New Yorkers as the stuff of theater. Playwright Ayad Akhtar’s “Disgraced,” which premiered in Chicago, won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2013 and opened on Broadway in October, deals with nothing less than the explosion of a friendship among four upwardly mobile young Americans of hyphenated ethnic and racial origins. An innocent favor lights the fuse, and the thin veneer of their collective sophistication is blown to shards. The play’s grosses took a sizable jump in November, even as chilly weather cooled the box office for other shows.

Yet the most timely, difficult issues have long been vigorously tolerated by New Yorkers as the stuff of theater. Playwright Ayad Akhtar’s “Disgraced,” which premiered in Chicago, won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2013 and opened on Broadway in October, deals with nothing less than the explosion of a friendship among four upwardly mobile young Americans of hyphenated ethnic and racial origins. An innocent favor lights the fuse, and the thin veneer of their collective sophistication is blown to shards. The play’s grosses took a sizable jump in November, even as chilly weather cooled the box office for other shows.

Attempts to suppress the Met’s “Klinghoffer” production were somewhat successful. Met general manager Peter Gelb canceled its scheduled Live-in-HD cinema transmission and radio broadcast. But a full run of performances at Lincoln Center did take place. The New York City opera community, with its large Jewish component, remained respectful of the demonstrators who lined up across Lincoln Center for each performance, but ultimately seemed to take the opera in stride.

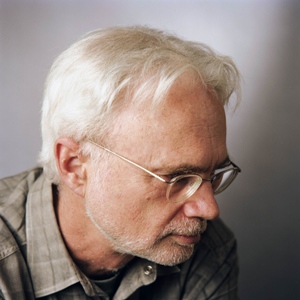

Already the work is a different experience than it was 23 years ago, when I saw the world premiere of “Klinghoffer” at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. I was working on a magazine article that would be published in The New York Times Sunday Magazine on Aug. 25, 1991, prior to the U.S. premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. John Adams, then 43, was still considered a renegade minimalist who was an affront to the classical establishment, though flush with the success of his first opera “Nixon in China,” spearheaded by Sellars as director. Sellars was in his mid-30s at the time, as were the poet-librettist Alice Goodman and the choreographer Mark Morris. Their brash, mocking take on the imperfect heads of state who achieved the Sino-American thaw had taken the world by storm.

Already the work is a different experience than it was 23 years ago, when I saw the world premiere of “Klinghoffer” at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. I was working on a magazine article that would be published in The New York Times Sunday Magazine on Aug. 25, 1991, prior to the U.S. premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. John Adams, then 43, was still considered a renegade minimalist who was an affront to the classical establishment, though flush with the success of his first opera “Nixon in China,” spearheaded by Sellars as director. Sellars was in his mid-30s at the time, as were the poet-librettist Alice Goodman and the choreographer Mark Morris. Their brash, mocking take on the imperfect heads of state who achieved the Sino-American thaw had taken the world by storm.

For their next project, Sellars searched in what the creative team referred to as the “danger zone of the historical present” for something equally audacious, rich and difficult. Adams said that when he heard the “Klinghoffer” title, which Sellars suggested, he knew the idea was right for him. The resultant opera would both dramatize and meditate upon the 1985 hijacking and murder.

Sellars’ team rehearsed in the immediate wake of Desert Storm — the U.S.-led response to Iraq’s invasion of oil-rich Kuwait — and in the atmosphere of the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwā calling for the execution of Salman Rushdie. Back then, the concern was not so much about Jewish pushback as it was about the opera’s potential as a flashpoint for Arab anger; Brussels itself was 15 percent Arab.

Out of precaution the Monnaie theater ditched its originally planned posters, which showed oil wells on fire, and instead ran virtually identical excerpts from the Quran and the Torah, on either side of the theater entrance, that gave accounts of the handmaiden Hagar’s expulsion into the desert with her son by Abraham, called Ishmael, known as a patriarch of Islam. (Israelites knew the same Abraham as a patriarch, through son Isaac, born of Abraham’s wife Sarah.) On the eve of the Brussels premiere, images of the Achille Lauro were back on TV over news that one of the Palestinian guerrilla leaders involved in the hijacking, Abdul Rahim Khaled, had been captured in Greece on suspicion of planning to bomb a British bank.

Out of precaution the Monnaie theater ditched its originally planned posters, which showed oil wells on fire, and instead ran virtually identical excerpts from the Quran and the Torah, on either side of the theater entrance, that gave accounts of the handmaiden Hagar’s expulsion into the desert with her son by Abraham, called Ishmael, known as a patriarch of Islam. (Israelites knew the same Abraham as a patriarch, through son Isaac, born of Abraham’s wife Sarah.) On the eve of the Brussels premiere, images of the Achille Lauro were back on TV over news that one of the Palestinian guerrilla leaders involved in the hijacking, Abdul Rahim Khaled, had been captured in Greece on suspicion of planning to bomb a British bank.

There were other concerns, primarily artistic. Adams was still on the defensive as a composer in those days, rocked by reviewers who hated “Nixon in China” and who felt that minimalism itself was ridiculous. Donal Henahan, writing in The New York Times, opined that “Mr. Adams does for the arpeggio what McDonald’s did for the hamburger.” Though other critics had begun to lighten up, Adams still felt embattled: “You have to realize how unbelievably humiliating it is to me to read, ‘Well, maybe “Nixon” isn’t all bad but the music still stinks and the libretto is still naïve.’ I mean, that’s the sort of thing you have to put with, year after year, until these people finally get sent to the glue factory and somebody else comes in, or, more likely, until some younger composer comes along that they can hate even more.”

Today, Adams can afford the statesman’s gentler tone, but back then the rigorously post-serial European tradition still held sway along the so-called Columbia-Princeton axis. “For many years, I felt so inadequate because I couldn’t explain my procedure like Milton Babbitt at Princeton could, but now I think I’m right and they’re wrong,” Adams said at the time. “Do you think Mozart had pre-compositional charts? Of course not.” The composer of “Nixon in China” aligned himself philosophically with post-modern architects like Michael Graves and Frank Gehry, who took so-called pop stuff seriously as influences.

And Sellars was behind him, pushing. One of the most memorable moments in “Klinghoffer” comes after the invalid is shot. It’s an aria for the falling body as it goes into the ocean that also serves as an allegory for all the Jews who perished without a trace. At the Met, baritone Alan Opie and conductor David Robertson inbued this scene with touching quiet and gravitas. But years before, back in Brussels, Sellars had said his problem was getting Adams to slow it down:

And Sellars was behind him, pushing. One of the most memorable moments in “Klinghoffer” comes after the invalid is shot. It’s an aria for the falling body as it goes into the ocean that also serves as an allegory for all the Jews who perished without a trace. At the Met, baritone Alan Opie and conductor David Robertson inbued this scene with touching quiet and gravitas. But years before, back in Brussels, Sellars had said his problem was getting Adams to slow it down:

“John’s major thing is that he is made to feel, by all these music critics and by the academic music establishment, terribly guilty for how heartfelt his work is. The ‘Aria of the Falling Body’ is this perfectly amazing thing, but it happens click-click-click according to John. It takes the performers to get him to agree to inch back, to allow him to face what he’s written.”

Meanwhile, Sellars and Goodman actually shied away from the use of captions. So-called surtitles were still relatively new and hugely controversial, hard to fathom today, but Adams likened the issue to gun control and abortion: “There’s no faster way to get people screaming at each other.” Adams deemed the captions essential for clarity, but he lost the first go-around. Instead the dense poetic text was sung, in English, by a Dutch-speaking chorus without translations, leaving much of the meaning a puzzle, especially since singers were all similarly clothed and took on various roles in an opera that no one had seen before.

The Tom Morris production at the Met builds upon a generation of practical lessons learned since Brussels about how best to communicate the opera in all aspects. Met audiences were given many more specific historical details of the hijacking and the murder of the Klinghoffer than its original 1991 audience, its memory still vivid, would have required.

One character, Omar, originally a trouser role for a mezzo-soprano intended to depict an adolescent terrorist, was performed at the Met by a dancer (the diminutive Jesse Kovarsky) instead of a singer. The words originally given to Omar were sung by a female character, perhaps Omar’s mother, who was seen imprinting upon this young man her idealized vision of a hero yearning to “walk in Paradise within two days.” By the time she finished singing, the youth had picked up the murder weapon. There was the sense conveyed of a tragedy compounding for generations.

The Tom Morris production overall achieved a somber, meditative wallop, not dissimilar to the more abstract Sellars original. The contribution of the Met Opera Chorus, prepared by chorus master Donald Palumbo, was central. When you add up the total number of minutes in this three-hour opera devoted to amassed voices – not only the twin choral pillars for the exiled Palestinians and the exiled Jews, but also subsequent choral evocations of ocean, of night, of desert and of day, all richly allegorical in nature – you are easily at a third of the whole. Like structural pilings in a deep foundation, the choruses bear the opera’s weight, and for this listener at least, they linger prominently in memory.

The opera’s final word, however, belongs to the character of Marilyn Klinghoffer, sung by Michaela Martens at the Met, whose aria begins in convulsive fury aimed at the exhausted captain (Paul Szot) who has brought the news of her husband’s death. “You embraced them!” Marilyn lashes out in an instantly recognizable human howl. And then, by contemplative degrees, she carries the opera to its end.

The opera’s final word, however, belongs to the character of Marilyn Klinghoffer, sung by Michaela Martens at the Met, whose aria begins in convulsive fury aimed at the exhausted captain (Paul Szot) who has brought the news of her husband’s death. “You embraced them!” Marilyn lashes out in an instantly recognizable human howl. And then, by contemplative degrees, she carries the opera to its end.

Her lament is the musical summit, an aria that Adams says that he knew “had to be the most important single musical moment” he had ever written, and it travels from its first mad cry through protracted grief and distraction (“I can’t recall the last sight I had of him”) to an image of her husband “rising from my heart into the world to come,” and the final, flat line: “They should have killed me. I wanted to die.”

Adams told me he once saw a documentary of Picasso drawing a huge picture on a wall with a piece of charcoal, “so close there was no way he could see what he was doing. It was just a totally unconscious, intuitive, visceral act on his part. That’s the way I wrote that scene.” Adams’s pure, gut intuition was exactly right.

Related Links:

- Behind the headlines: Read the backgrounder at metopera.org

- Director Tom Morris defends the opera: Watch a video of the interview at the time of the production’s London premiere.

- The daughters of Leon Klinghoffer objected to the Met’s scheduling of the work: Read their complete statement.

- More photos, audio and video clips: Visit the Met’s “Klinghoffer” mini-site.

Tags: Achille Lauro, Alan Opie, Alice Goodman, Ayad Akhtar, David Robertson, Death of Klinghoffer, Donald Palumbo, English National Opera, Gospel According to the Other Mary, Jesse Kovarsky, John Adams, Leon Klinghoffer, Mark Morris, Metropolitan Opera, Michaela Martens, Monnaie, Nixon in China, On the Transmigration of Souls, Paulo Szot, Peter Sellars, Tom Morris