Conjuring ghosts and dreams, Lyric Opera’s new ‘Werther’ lifts the spirit of a melodrama

“Werther” by Jules Massenet, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago through Nov. 26 ★★★★

“Werther” by Jules Massenet, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago through Nov. 26 ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

One is so torn watching tenor Matthew Polenzani’s vocally resplendent performance in the title role of a new production of Massenet’s “Werther” at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. While you’re sitting there beguiled by Polenzani’s authoritative, richly modulated sound, something deep inside is spurring you to bolt from your seat, rush onto the stage and just shake that determinedly miserable character he’s playing.

To music of endless beauty, young Werther pines – with unflinching single-mindedness – for Charlotte (French mezzo-soprano Sophie Koch), the prize beyond reach. He continues down that same sorry path even after fair Charlotte is married, and then he kills himself. Meanwhile, he manages to infect Charlotte with his romantic vapors, though her marriage has hardly bounced off to an auspicious start anyway. So Werther dies (an extended, effusive death, of course) and Charlotte is left to get over it. Curtain.

To music of endless beauty, young Werther pines – with unflinching single-mindedness – for Charlotte (French mezzo-soprano Sophie Koch), the prize beyond reach. He continues down that same sorry path even after fair Charlotte is married, and then he kills himself. Meanwhile, he manages to infect Charlotte with his romantic vapors, though her marriage has hardly bounced off to an auspicious start anyway. So Werther dies (an extended, effusive death, of course) and Charlotte is left to get over it. Curtain.

By any rational lights, this is not a compelling story. Werther might qualify as a kind of unintended anti-hero, born to lose and all that, except that he’s essentially aimless, feckless, self-pitying and morbid. But he’s also just the sort of figure that expressed the Romantic zeitgeist of 19th century Europe, and certainly it is Massenet’s inspired, earnest, indeed touching music that keeps this melodrama on the boards.

To the great credit of all parties, the Lyric’s new take, a co-production with the San Francisco Opera directed by Francisco Negrin and designed by Louis Désiré, infuses “Werther” with an imaginative freshness that allows us to get round that long-suffering lad just enough to find some other elements to engage our wits.

To the great credit of all parties, the Lyric’s new take, a co-production with the San Francisco Opera directed by Francisco Negrin and designed by Louis Désiré, infuses “Werther” with an imaginative freshness that allows us to get round that long-suffering lad just enough to find some other elements to engage our wits.

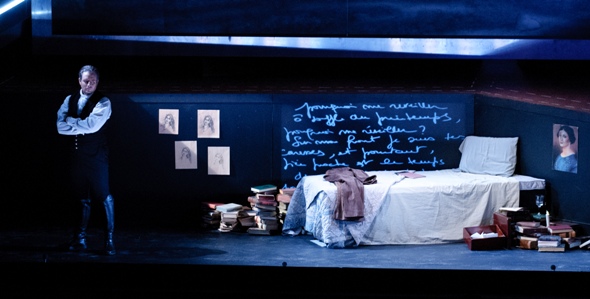

Désiré’s split-level set creates a garret-like space downstage where the solitary Werther can fling himself upon his bed in despair while a wall-mounted video screen reveals his vision of the near but oh-so-distant Charlotte. We watch Werther splash a wall with Charlotte’s name in red paint. The main set, chiefly Charlotte’s home, spreads outward from a stairway – decidedly Parnassus-like — leading up toward the girl’s unseen bedroom. A stylized clump of tree trunks topped by a large, changeable framed image of leaves chronicles the passing seasons. The whole is surrounded by a chrome-rimmed fence, the cold barrier to Werther’s dream.

Negrin’s reimagining of this over-the-top romance has a lot going for it, especially in his radical treatment of the would-be lovers’ last two encounters. Their penultimate meeting, in the married Charlotte’s home, is depicted as her dream and it is deeply affecting as she hears and responds to that familiar voice and its too-familiar rhetoric.

The last moments between Werther and Charlotte occur just after he has shot himself. Its length challenges even the suspension of disbelief, but Negrin deals with it slyly but turning Werther into a ghost. Charlotte addresses the body on the ground, unaware of the real source of his answering voice behind her. One gets the sense that Charlotte simply hasn’t quite caught up with real time or the actuality of Werther’s death. (But why Negrin turns Werther into a trinity of figures for the last scenes, I confess, escapes me. His third incarnation seems altogether underemployed.)

Another intriguing Negrin twist concerns the letters accumulated from Werther that Charlotte revisits and reads aloud, to herself in most accounts. Here, Negrin has her reading them to her husband! And while the contents never really edge into protestations of love, Charlottte’s husband grows understandably more annoyed. Just as Polenzani and Koch play the dream and ghost sequences to fine effect, so here Koch and baritone Craig Verm as her husband convey all that’s gone wrong in this marriage.

Another intriguing Negrin twist concerns the letters accumulated from Werther that Charlotte revisits and reads aloud, to herself in most accounts. Here, Negrin has her reading them to her husband! And while the contents never really edge into protestations of love, Charlottte’s husband grows understandably more annoyed. Just as Polenzani and Koch play the dream and ghost sequences to fine effect, so here Koch and baritone Craig Verm as her husband convey all that’s gone wrong in this marriage.

Lyric music director and conductor Sir Andrew Davis, who marks the 25th anniversary of his Lyric debut with this production, imbues Massenet’s score with a fetching blend of urgency and grace. Stylistically, Davis’ elegant, indulgent leadership – as well as the Lyric Opera Orchestra’s fluent performance – would be perfectly at home at the Paris Opera.

In her American debut, Koch not only gives lustrous voice to Charlotte but also elicits our sympathy for this woman caught between a troubled marriage she wishes to honor and the fantasy of Werther’s fulsomely urged option. As Charlotte’s wary husband, Verm offers a subtle vocal portrait that evolves from mellowness to dark agitation, all the while evoking an almost spectral quality that haunts Charlotte’s life. Soprano Kiri Deonarine, a second-year student at the Lyric’s Ryan Opera Center, offers vivacious singing as Charlotte’s sister Sophie to round out the core cast.

Related Links:

- Performance dates and tmes: Details at LyricOpera.org

- Lyric’s new season offers scenic route with nine stops: Read the preview at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Captions and credits: Home page and top: Alone in his room, Werther (Matthew Polenzani) pines for the inaccessible Charlotte (Sophie Koch), whose imagined image appears on a video screen. Descending: Though it can never be, Charlotte (Sophie Koch) is drawn into Werther’s (Matthew Polenzani) fantasy. Charlotte (Sophie Koch) clutches a bouquet from Werther. Her sleep disturbed by dreams, Charlotte (Sophie Koch) communes with her would-be lover Werther (Matthew Polenzani). (Photos by Dan Rest) Below: Stylized trees mark the progressing seasons in the Lyric Opera’s new production of “Werther.” Kneeling over the body of Werther, Charlotte bids farewell to his spirit (Matthew Polenzani, standing). Alone, Werther (Matthew Polenzani) contemplates his fate without Charlotte. (Photos by Robert Kusel)

Tags: Craig Verm, Francisco Negrin, Kiri Deonarine, Louis Desire, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Massenet, Matthew Polenzani, Sir Andrew Davis, Sophie Koch, Werther