Even as Muti cast his light on Verdi’s ‘Aida,’ unplanned drama ruled over the CSO stage

The show must go on. “Aida” starred two different sopranos under Muti during the opera’s run at Orchestra Hall, and the captioning failed. But the opera was grand. (Photos © Todd Rosenberg)

Review: “Aida” by Giuseppe Verdi. Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Chorus and soloists conducted by Riccardo Muti, at Orchestra Hall.

By Nancy Malitz

While on tour with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Vienna in 2014, music director Riccardo Muti called upon Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova to stand in for Tatiana Serjan after a single rehearsal of Verdi’s Requiem. A strong soprano with an exquisite musical sensibility, Stoyanova had recorded the tragic role of Desdemona in Verdi’s “Otello” with Muti earlier on the CSO’s Resound label.

But on Friday, June 21, when Stoyanova sang with Muti in the title role of Verdi’s “Aida” at Orchestra Hall, she clutched a handkerchief and sang conservatively through the part of the once-proud Ethiopian king’s daughter, who is enslaved and caught in a tragic love triangle. It was no surprise to learn, on June 23, that someone would sub for Stoyanova. The young Cuban-American soprano Elaine Alvarez would sing the second of three performances in a sold-out run. Alvarez was not entirely unknown either to Chicago or to Muti. She had been a successful last-minute replacement as Mimi in “La Boheme” at the Lyric Opera in 2007, and Muti had conducted her in a Ravenna Festival tour in 2008, as a soloist in Rossini’s “Stabat Mater.”

For Alvarez to step in without opportunity to rehearse demanded bravery. Thus neither performance was ideal, but both provided a workable platform for Muti’s concept, honed for decades. In both cases, one could focus on other key elements without which this drama is nothing, such as the role of Amneris, the ruthless Egyptian princess sung by the brilliant mezzo-soprano Anita Rachvelishvili. She was in regal command, her voice ferocious in anger, meltingly delicious in the throes of love. Her second act scene, which begins with “Ah, vieni, amor mio” (Ah, come my love) and ends with “Trema, vil schiava!” (Tremble, base slave!”) as her slave Aida begs for pity, brought the house down both nights. Riveting to behold, Rachvelishvili is very smart, bursting with temperament and vocal power.

The object of Aida’s and Amneris’ affections is the warrior Radamés (tenor Francesco Meli, in robust voice). His heart is with the slave girl (“Celeste Aida”), which is tantamount to a death sentence for them both.

Without stage scenery, attention turned to another prominent player – the orchestra, replenished with a new generation of musicians in key positions of winds and brass, and exhibiting extraordinary intensity and lyrical finesse. The boiling emotions and impossible effects that Muti drew out of the ensemble were so beautifully drawn that Verdi’s music seemed to convey the characters’ involuntary reactions, anticipating their anxiety, anger and alarm even as the words were barely forming.

Onstage, instead of in an opera pit, the CSO was great fun to watch, whether in tandem with the mighty-sounding Chicago Symphony Orchestra Chorus, prepared by director Dwain Wolfe, or drenched in the exotic color of the opera’s diaphanous ballets. The flutes, in their most velvety registers, gave the graceful music of the Sacred Dance of the Priestesses a sense of ancient ritual. The hushed third act commenced with delicate violin staccatos at octaves perfectly aligned – a magical achievement along with the modal harmonies that gently evoked the rippling, moonlit Nile.

And the grand pageant of the second act – the Egyptian nation celebrating its victory in war – was an orchestral and choral sequence of heady pomp and irresistible repetition. An indulgent spectacle, replete with the ceremonial trumpets of a victorious nation that expected to last forever, it was given without a trace of irony.

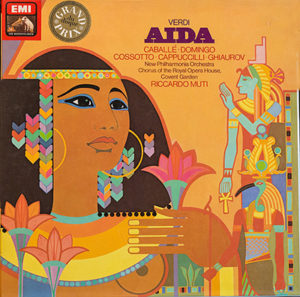

Muti is as straight a line to the source as we have today. He studied with the conductor Antonino Votto, who studied with the conductor Arturo Toscanini, who at the age of 19, as an assistant chorus master, conducted “Aida” from memory under emergency conditions while on tour with an opera company in South America, and then went back to Milan as a cellist in the La Scala opera pit for the “Otello” world premiere under Verdi’s supervision. One of Muti’s most famous recordings was his first, an “Aida” from 1974, out of London, when he was still in his early thirties. It was with Montserrat Caballé as Aida, Fiorenza Cossotto as Amneris and Placido Domingo as a Radamés of youthful vigor. Other recordings of this opera are readily available, but Muti’s early recording remains a touchstone and his interpretation still widely revered.

Muti is as straight a line to the source as we have today. He studied with the conductor Antonino Votto, who studied with the conductor Arturo Toscanini, who at the age of 19, as an assistant chorus master, conducted “Aida” from memory under emergency conditions while on tour with an opera company in South America, and then went back to Milan as a cellist in the La Scala opera pit for the “Otello” world premiere under Verdi’s supervision. One of Muti’s most famous recordings was his first, an “Aida” from 1974, out of London, when he was still in his early thirties. It was with Montserrat Caballé as Aida, Fiorenza Cossotto as Amneris and Placido Domingo as a Radamés of youthful vigor. Other recordings of this opera are readily available, but Muti’s early recording remains a touchstone and his interpretation still widely revered.

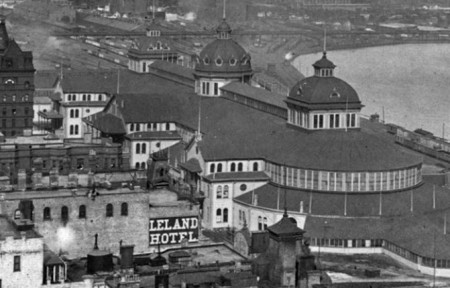

Meanwhile Chicago’s own history with “Aida” over the years is pretty impressive. The city hosted performances of “Aida” on in January 1874, little more than two years after the Cairo world premiere celebrating the opening of the Suez Canal. Chicago’s premiere took place at the Grand Opera House on North Clark, starring Annie Louise Cary and Italo Campanini.

The most lavish “Aida” in Chicago’s history featured a cast of thousands. It took place in 1885 across the street from where Orchestra Hall now stands, at the site of the Art Institute. The vast Interstate Industrial and Exposition Building, inspired by London’s Crystal Palace, had an opera house inside, and according to Robert C. Marsh’s book “150 Years of Opera in Chicago,” the pit had room for 155 musicians and audience seating for 6,000. “Aida” was advertised as having 500 supernumeraries posing as captured Ethiopians, 600 members of the state militia marching as the Egyptian army, a supplemental chorus of 350, and more. (Apologies to the soprano, Adelina Patti; the tenor, known as Nicolini, and the rest of the plucky, doubtlessly hoarse, cast.)

Thus Chicago has “Aida” in its bones. Lillian Nordica sang the title role in the first season (1889-90) of the new Auditorium Theater along Michigan Avenue. The great Rosa Raisa, Claudia Muzio, and Zinka Milanov all sang their Aidas here in the 20th century. Chicago’s own Lyric Opera put on “Aida” in its second season (1955) with Renata Tebaldi and Astrid Varnay as the rivals in love. The company then did “Aida” runs twice in the ’60s (with Leontyne Price and Fiorenza Cossotto in 1965); twice in the ’80s, once in the ’90s and again in 2004, but not recently. No wonder it felt like it was time.

Mark the calendar now – Rachvelishvili returns next season to star as the jealous Santuzza in CSO concert performances of Mascagni’s masterpiece “Cavalleria Rusticana” led by Muti on Feb.6, 7, and 8.

Meanwhile, it is greatly to be desired that some sort of projected captioning solution is found as the CSO proceeds with these operas-in-concert. The hall’s onstage overhead screen containing the translations broke down in the first act of the first performance, sending many in the audience scrambling for printed librettos. There were no captions for the second performance, either. Unfortunately, one cannot assume that an American symphony crowd knows any opera line by line, even “Aida.” Captions may seem an awkward reality, but today’s audiences are accustomed to them in opera houses and concert halls alike. Projections allow the eyes to stay onstage where they belong.