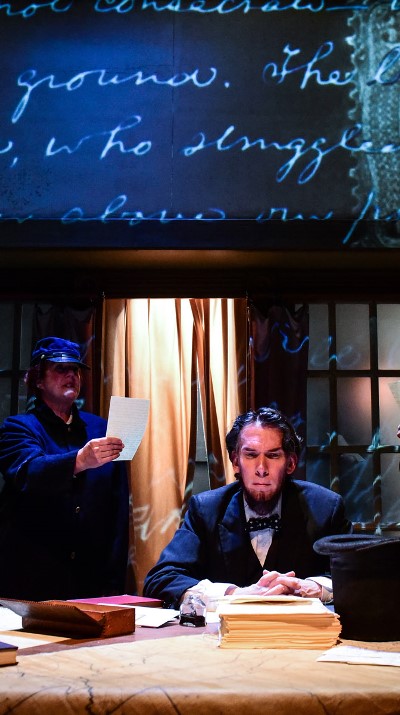

Role Playing: Lawrence Grimm found Lincoln first in pages of history, then within himself

Interview: The tall actor says he needed to sharpen his wits to keep up with icon of “Heavens Are Hung in Black’ at Shattered Globe.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Lawrence Grimm stands 6 feet 4 inches tall – the same height as Abraham Lincoln. It wasn’t height that worried Grimm when he took on his nuanced and profoundly human portrayal of Lincoln in James Still’s “The Heavens Are Hung in Black” at Shattered Globe Theatre. What concerned the actor were the iconic dimensions of the 16th president, the towering figure whose wisdom would guide the nation through its greatest crisis.

“Those were big shoes to fill,” says Grimm, “and of course Lincoln’s life has been documented in so many books filled with very strong opinions about who he was and what he did. But when I stopped worrying about what I hadn’t read and simply began doing what actors do – when I began memorizing the part and creating my own persona – that feeling of being absolutely overwhelmed went away.”

“Those were big shoes to fill,” says Grimm, “and of course Lincoln’s life has been documented in so many books filled with very strong opinions about who he was and what he did. But when I stopped worrying about what I hadn’t read and simply began doing what actors do – when I began memorizing the part and creating my own persona – that feeling of being absolutely overwhelmed went away.”

Still’s highly concentrated play is set in an early phase of the Civil War when the Union’s campaign seemed to be mired in indecision and miscalculation. Lincoln mulls the idea of revoking slavery, but emancipation is not at the top of his mind. First and foremost is the preservation of the Union. Yet even as his burdens weigh upon him, he finds solace in his young son Tad and comforts his wife Mary in her grief over the fatal illness of another son, Willie. War and circumstance will not wait, however: Almost breath by breath, Lincoln turns from affairs of state to family to a sleepless longing for the contentment and friendships of life back home in Illinois.

“There was a compassion in Lincoln that was not a stretch for me,” says Grimm. “He was a man of kindness, openness, curiosity and intuitive intelligence. For me, the key challenge – the stumbling block, really – was how fast this man’s brain worked. In portraits, he sometimes looks a bit sloppy and awkward in body and dress. But his mind was incredibly agile.

“In the second act, there’s what I call the spinning-plate scene where Lincoln is trying to entertain Tad while dealing with officials in his office complaining that General McClellan isn’t really leading the army, and so on. All this seemed like Lincoln can’t focus, and I didn’t know what to do. So I wrote to the playwright for advice.

“In the second act, there’s what I call the spinning-plate scene where Lincoln is trying to entertain Tad while dealing with officials in his office complaining that General McClellan isn’t really leading the army, and so on. All this seemed like Lincoln can’t focus, and I didn’t know what to do. So I wrote to the playwright for advice.

“Still wrote back saying that Lincoln suffered from melancholy – what we would called clinical depression today – but not ADD (attention deficit disorder). The problem was that Larry the actor wasn’t keeping up with all these synapses. Lincoln could burst into tears without shame, and within seconds snap to a judgment about a document that required a decision. He could simply connect more dots more quickly than most people.”

Grimm found the humanity of the historic Lincoln in small things, like the slightly drawled speech of this Kentucky native who spent part of his youth in southern Indiana before the family moved on to Illinois. And Lincoln was fond of story-telling. Still’s play is peppered with spontaneous anecdotes.

“I love the narratives he could spin,” the actor says. “And none of the stories happen by accident. There’s always an objective, a point that he’s making. I call them his little Garrison Keillor moments.”

If the Lincoln of Still’s play shows a quick mind, he also betrays one reeling under the stress of outsized events. Lincoln has trouble sleeping, and his insomnia leads him down pathways that cross borders of place and time.

“In Lincoln’s apparitions, James (Still) has given us a really great convention,” says Grimm. “When you’re sleep deprived, it’s worse than being drunk, and so Lincoln’s fantasies all make perfect sense. People come into and out of his head based on his impulses. But we didn’t want a ‘Christmas Carol’-like Scrooge. These aren’t separate events, but interconnected things going on in his mind.

“In Lincoln’s apparitions, James (Still) has given us a really great convention,” says Grimm. “When you’re sleep deprived, it’s worse than being drunk, and so Lincoln’s fantasies all make perfect sense. People come into and out of his head based on his impulses. But we didn’t want a ‘Christmas Carol’-like Scrooge. These aren’t separate events, but interconnected things going on in his mind.

“When in one dream-state he meets (Confederate President) Jefferson Davis, Lincoln talks about how deeply he feels the loss of life in war. Davis doesn’t feel that at all. He believes the sacred cause transcends the toll of human life. If you’re a leader, it’s a liability to feel as much as Lincoln feels. He is Hamlet-like, and there’s a decisiveness in Davis that Lincoln envies.”

Lincoln looked for respite from the war even in fleeting moments, Grimm says. “He enjoyed his children. He was a hands-on dad when that wasn’t typical. There’s a scene where Lincoln is laughing with Tad when (Secretary of War) Stanton is being quite serious and reprimands Lincoln for his frivolity. Lincoln replies, ‘I laugh because otherwise I would weep.’ It’s his survival mechanism for getting from one day to the next.”

Just as Lincoln has his stress-induced visions, so does his wife Mary Todd (Linda Reiter), who is sometimes his confidante and counsellor, other times his supplicant. Anguished by the loss of their son Willie, Mary imagines that she sees the boy in his childish vigor. She feels isolated and clamors to see her husband.

“At one point, Lincoln says, ‘Tell her that I’m waging a war,’” notes Grimm. “But her own pain trumps even that. He feels such great empathy that she’s seeing Willie. We sometimes underestimate the human capacity for dealing with trauma and stress, to negotiate, navigate and stay sane. Lincoln gets painted in mythological proportions, but the character within him was profoundly human.”

“At one point, Lincoln says, ‘Tell her that I’m waging a war,’” notes Grimm. “But her own pain trumps even that. He feels such great empathy that she’s seeing Willie. We sometimes underestimate the human capacity for dealing with trauma and stress, to negotiate, navigate and stay sane. Lincoln gets painted in mythological proportions, but the character within him was profoundly human.”

Mary Todd likewise lived – indeed, still lives – in dual images, Grimm says: “One may think of her as fragile, but Linda brings out the strength in her – the woman who’s governing the governor. Mary Todd displays a level of insight that is heightened by Linda’s performance, which is wise and intelligent.”

In forging his closely inflected image of Lincoln at the center of calamity, Grimm was abetted by a director who brought more than theatrical savvy to the enterprise: Louis Contey is a lifelong Lincoln enthusiast who, as Grimm puts it, “has his own Lincoln library. When I asked him to suggest some books I might read, he sent me a two-page annotated list as a place to start. So there I was trying to play one of the greatest men in American history under the eye of an expert on the subject.

“But Lou was terrific. His appreciation, understanding and admiration for Lincoln is deeply personal. Yet he was completely flexible and open to every idea I had. He would just say, ‘This is what’s going on. Imagine what it would be like.’ Permission is sometimes the greatest gift you can get from a director. Lou built my confidence. He could not have known how intimidated I was.”

Related Link:

- Review of ‘The Heavens Are Hung in Black’: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

More Role Playing Interviews:

- Cristina Panfilio spreads wings she didn’t know she had as midsummer Puck

- Tyla Abercrumbie was set to run little ‘Hot Links’ café, but why was she there?

- AnJi White, as Catherine Parr, learned to keep her wits – to keep her head

- Adam Bitterman, unlikely florist in ‘Seedbed,’ dug deep to create a rare bloom

- Danny McCarthy, pushing broom in ‘The Flick,’ finds vital pulse in long silences

- Mierka Girten, actor with MS, knows wound behind her character’s scars

- Sandra Marquez, as Clytemnestra, sees an exceptional woman in the Greek queen

- Brian Parry says he summoned courage before wit as George in ‘Virginia Woolf’

- Tracy Michelle Arnold debunks madness as force that drives Blanche DuBois

- Christopher Donahue, as Ahab, finds sea’s depth in sadness of a vengeful soul

- Lance Baker embodies ennui, despair of fugitive Jews in ‘Diary of Anne Frank’

- Francis Guinan embraces conflict of father who fled from grim truth in ‘The Herd’

- Sophia Menendian reached back (but not far) as plucky Armenian refugee of 15

- Lindsey Gavel’s distressed Masha, in ‘Three Sisters,’ began with a touch of cheer

- Hollis Resnik felt personal bond with zealous, skeptical scholar in ‘Good Book’

- A.C. Smith is ready undertaker, lord of diner world in ‘Two Trains Running’

- Lia D. Mortensen’s intense portrait of a mentally failing scientist holds mirror to life

- Siobhan Redmond sees re-formed Lady Macbeth as valiant queen in ‘Dunsinane’

- Eileen Niccolai harnessed a storm of emotions to create spark in Williams’ Serafina

- Steve Haggard, aiming at reality, strikes raw core of grieving man in ‘Martyr’

- Shannon Cochran found partners aplenty in sardonic, twice-told ‘Dance of Death’

- Natalie West scaled back comedy to nail laughs, touch hearts in ‘Mud Blue Sky’

- Dave Belden, actor and violinist, adjusted pitch for ‘Charles Ives Take Me Home’

- Joseph Wiens starts at full throttle to convey alienation of ‘Look Back in Anger’

- Shane Kenyon touches charm and hurt of lovable loser in Steep’s ‘If There Is’

- Ramón Camín sees working class values in Arthur Miller’s tragic Eddie Carbone

- Hillary Marren’s charming, rapping witch in ‘Woods’ shapred by hard work, free play

- Mary Beth Fisher embraces both hope, despair of social worker in ‘Luna Gale’

- Brad Armacost switched brothers to do blind, boozy character in ‘The Seafarer’

- Karen Woditsch shapes vowels, flings arms to perfect portrait of Julia Child

- Ora Jones had to find her way into Katherine’s frayed world in ‘Henry VIII’

- Kareem Bandealy tapped roots, hit books for form warlord in ‘Blood and Gifts’

- Eva Barr explored two personas of Alzheimer’s victim to find center of ‘Alice’

- Darrell W. Cox sees theater’s core in closed-off teacher of ‘Burning Boy’

- Chaon Cross turned Court stage into a romper room finding answers in ‘Proof’

- Dion Johnstone turned outsider Antony to bloody purpose in ‘Julius Caesar’

- Noir films gave Justine Turner model for shadowy dame in ‘Dreadful Night’

- Anish Jethmalani plumbs agony of good man battling demons in ‘Bengal Tiger’

- Gary Perez channels his Harlem youth as quiet, unflinching Julio in ‘The Hat’

- Kamal Angelo Bolden sharpened dramatic combinations to play ‘The Opponent’

- In wheelchair, Jacqueline Grandt explores paralysis of neglect in ‘Broken Glass’

- James Ridge thrives in cold skin of Shakespeare’s smiling serpent, Richard III

- Stephen Ouimette brews an Irish tippler with a glassful of illusions in ‘Iceman’

- Ian Barford revels in the wiliness of an ambivalent rebel in Doctorow’s ‘March’

- Chuck Spencer flashes a badge of moral courage in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Price’

- Rebecca Finnegan finds lyrical heart of a lonely woman in ‘A Catered Affair’

- Bill Norris pulled the seedy bum in ‘The Caretaker” from a place within himself

- Diane D’Aquila creates a twice regal portrait as lover and monarch in ‘Elizabeth Rex’

- Dean Evans, in clown costume, enters the darkness of ‘Burning Bluebeard’

- Dan Waller wields a personal brush as uneasy genius of ‘Pitmen Painters’

- City boy Michael Stegall ropes wild cowboy in Raven Theatre’s ‘Bus Stop‘

- Brent Barrett is glad he joined ‘Follies’ as that womanizing, empty cad Ben

- Sadieh Rifai zips among seven characters in one-woman “Amish Project”

- Kirsten Fitzgerald inhabits sorrow, surfs the laughs in ‘Clybourne Park’

- Janet Ulrich Brooks portrays a Russian arms negotiator in ‘A Walk in the Woods’

Tags: James Still, Lawrence Grimm, Linda Reiter, Louis Contey

2 Pingbacks »