‘Two Trains Running’ at Goodman: As tumult besets their world, diner denizens grasp at life

“Two Trains Running” by August Wilson, at Goodman Theatre, extended through April 19. ★★★★★

“Two Trains Running” by August Wilson, at Goodman Theatre, extended through April 19. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

We need a new word to describe the quality that makes every August Wilson play a red-letter event of any theater season. This single new descriptor would meld the two features that Wilson always mixes with such ineffable ease: charm and poignancy. They are the stuff of “Two Trains Running” at the Goodman Theatre, a beguiling portrait of the human condition as an uphill battle – and the difference a leap of faith can make.

In the series of 10 plays Wilson characterized as a decade-by-decade chronology of the black experience in America during the 20th century, “Two Trains Running” represents the 1960s. African Americans were pressing their demands for civil rights – a cause that saw its two most prominent advocates assassinated: Malcom X in 1965 and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968.

In the series of 10 plays Wilson characterized as a decade-by-decade chronology of the black experience in America during the 20th century, “Two Trains Running” represents the 1960s. African Americans were pressing their demands for civil rights – a cause that saw its two most prominent advocates assassinated: Malcom X in 1965 and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968.

Such is the tumultuous world outside the little diner in Pittsburgh’s mostly black Hill District, where Wilson’s play unfolds, in 1969. Working with an A-list of Chicago actors, director Chuck Smith goes straight to the plight and heart of folks just trying to put one day in front of another.

Memphis (Terry Bellamy) — who owns the diner designed to inviting detail by Linda Buchanan — is a hard-edged, practical man in middle age who lives with the bitter taste of the wrong done to him by white people back in his native Mississippi. He takes a jaundiced view of blacks’ on-again, off-again clamoring for justice and opportunity. He made it on his own; twice, actually.

But now Memphis is up against it again. Redevelopment has descended on the Hill District and the city is laying claim to his building – for a price that’s way below what he wants. He’s holding out for a hefty sum, and not a penny less.

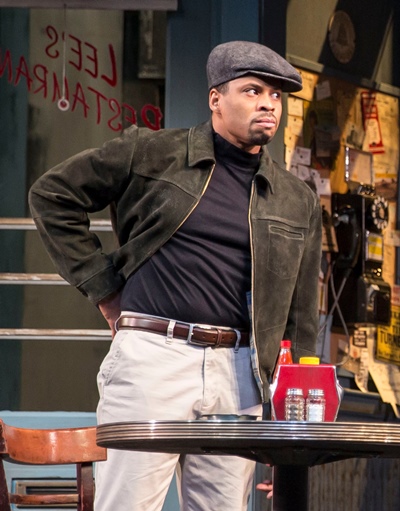

Holloway (Alfred H. Wilson), a senior regular at the diner, shares Memphis’ unsympathetic view of black agitation. Doesn’t matter whether the style is Malcom X’s harsh polemics or King’s non-violent disobedience: Look what it got both of them. Life is what it is; make the best of it. But young Sterling (Chester Gregory), an impetuous young man just out of prison, admires Malcom X (whose birthday the community is planning to celebrate at a rally). Mainly, though, Sterling just wants to find a job and avoid going back to the pen.

Holloway (Alfred H. Wilson), a senior regular at the diner, shares Memphis’ unsympathetic view of black agitation. Doesn’t matter whether the style is Malcom X’s harsh polemics or King’s non-violent disobedience: Look what it got both of them. Life is what it is; make the best of it. But young Sterling (Chester Gregory), an impetuous young man just out of prison, admires Malcom X (whose birthday the community is planning to celebrate at a rally). Mainly, though, Sterling just wants to find a job and avoid going back to the pen.

Three other habitués pepper the diner’s mix: the wealthy undertaker West (A.C. Smith), who figured out long ago that it was better to bury the dead than pursue a life that would lead him to his own early end; the young numbers runner Wolf (Anthony Irons), who constantly clashes with Memphis over use of the diner’s phone for his illicit gaming, and a mentally ill handyman called Hambone (Ernest Perry Jr.),. who for nearly 10 years has uttered few words apart from his bellowed demand that a local businessman pay him the ham promised for painting a fence.

The only woman is Risa (Nambi E. Kelley), the diner’s pretty cook and waitress, whose shadowed past has led her to scar her own legs with a knife. In a performance of gentle vulnerability, Kelley’s guarded waitress quickly catches the eye of recently sprung Sterling – funny and youthfully dashing in Gregory’s persona, but also vaguely dangerous. From the moment he lays eyes on her, Sterling sees his future with Risa and he lets her know it.

The only woman is Risa (Nambi E. Kelley), the diner’s pretty cook and waitress, whose shadowed past has led her to scar her own legs with a knife. In a performance of gentle vulnerability, Kelley’s guarded waitress quickly catches the eye of recently sprung Sterling – funny and youthfully dashing in Gregory’s persona, but also vaguely dangerous. From the moment he lays eyes on her, Sterling sees his future with Risa and he lets her know it.

But Risa gets no sweet talk from the boss. Business is slow, the city has underpriced his place, everything’s getting under Memphis’ skin and he takes it all out on Risa. Terry Bellamy is magnetic as the perpetually gruff Memphis. His clipped, almost monotonal delivery reflects his pugnacious outlook. He’s a fighter, and he speaks in jabs. Memphis has reason to be bitter, and Bellamy spills it all out in a graphic monologue that brings the play to its emotional peak.

August Wilson was a master of monologues, indeed a virtuoso wielder of language, and he distributes those lyrical riches among his characters. A.C. Smith, disarming in his muted eminence as the well-to-do undertaker West, applies his barrel-chested baritone with restrained potency as West presses Memphis to sell him the diner for less than he wants. In another of the play’s best moments, Smith’s self-made man explains how he didn’t set out to get rich – just to find a path around the daily danger of the life he once lived.

August Wilson was a master of monologues, indeed a virtuoso wielder of language, and he distributes those lyrical riches among his characters. A.C. Smith, disarming in his muted eminence as the well-to-do undertaker West, applies his barrel-chested baritone with restrained potency as West presses Memphis to sell him the diner for less than he wants. In another of the play’s best moments, Smith’s self-made man explains how he didn’t set out to get rich – just to find a path around the daily danger of the life he once lived.

One could argue that it’s the wise and philosophical Holloway, rather than Memphis, who occupies the play’s central place. He does so literally, sitting in the middle of the diner, in director Chuck Smith’s empathic staging. Alfred H. Wilson’s Holloway casts a clear, albeit wry, light as a man schooled in contentment by the experience of a long life lived.

Skulking at the edges is Wolf, the numbers guy. In Anthony Irons, this Wolf is a paradox: a tall figure in plaid bell-bottom pants (hats off to costumer Birgit Rattenborg Wise) who really prefers to keep a low profile. He makes book, but he doesn’t make the rules. All that stuff going on outside is not happening in the world Wolf knows.

A greater paradox resides in Hambone. Ernest Perry Jr. is disturbingly credible as the demented handyman who never stops ranting about the ham payment he’s due. When he babbles in Memphis’ face, Memphis snaps back at him: Shut up. Stop. Get out of here with that bellowing. But Hambone wants his ham. He wants his ham. He wants his ham!

And that, essentially, is just what Memphis craves as well.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Preview of Goodman Theatre’s complete 2014-15 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: A.C. Smith, Alfred H. Wilson, Anthony Irons, August Wilson, Birgit Rattenborg Wise, Chester Gregory, Chuck Smith, Ernest Perry Jr., Goodman Theatre, Linda Buchanan, Nambi E. Kelley, Terry Bellamy, Two Trains Running