James Conlon, remembering Bernard Haitink, leads CSO concert of solemnity and brilliance

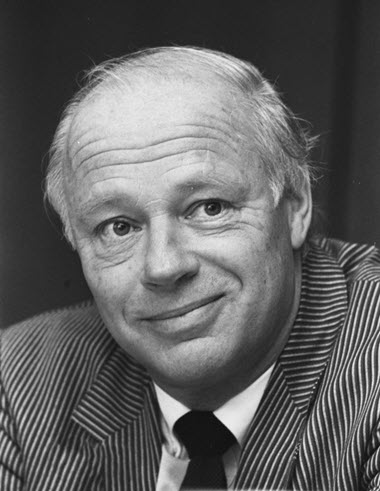

Conductor James Conlon tapped into the elegiac mood of his colleagues, who learned of former principal conductor Bernard Haitink’s death on October 21. (Concert photos byTodd Rosenberg)

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by James Conlon; Alexander Gavrylyuk, piano. At Orchestra Hall.

By Nancy Malitz

When Michael Tilson Thomas, convalescing from surgery, was forced to cancel his conducting engagement for Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts Oct. 21-23, the orchestra turned to James Conlon to take the dates. One of the smartest and most adaptable maestros in the business, the 71-year-old American is also a longtime friend of the CSO. He was music director of the Ravinia Festival from 2005-2015, leading the musicians in their summer digs for 11 seasons. And the relationship goes even further back: Conlon was only 27 when he first picked up the baton in front of these musicians, also at Ravinia, in 1977.

Thus it was no surprise that Conlon tapped into the elegiac mood of his colleagues, who had learned of the loss of Bernard Haitink, the CSO’s principal conductor from 2006 to 2010. The Dutch maestro passed away on Thursday, Oct. 21, at the age of 92, as the CSO and Conlon were readying their first performance of the week.

The Friday concert, which I attended, began with a profound reading of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet, arranged for string orchestra and retitled Chamber Symphony. It is Shostakovich’s cry of the heart from the depths of sadness, and it was amplified as if into a chorus of cries by the unique circumstance: Conlon told the audience that the orchestra was dedicating its performance to Haitink’s memory.

The music had flowed from Shostakovich’s pen in 1960, more than a decade after the Second World War ended, after the Russian composer walked through the bombed-out devastation of Dresden, once one of the world’s most exquisite cities, then still an ashen ruin.

His response was to write, in a grief-stricken rush, a string quartet of mesmerising sadness, shot through with a sighing four-note motif he frequently used, and which became known as his musical signature. (The D, for Dmitri, and the SCH, for the first three letters of the composer’s last name, are pronounced in German as “Day, Ess, Say, Ha.”)

His response was to write, in a grief-stricken rush, a string quartet of mesmerising sadness, shot through with a sighing four-note motif he frequently used, and which became known as his musical signature. (The D, for Dmitri, and the SCH, for the first three letters of the composer’s last name, are pronounced in German as “Day, Ess, Say, Ha.”)

The composition itself is a soaring beauty, among the greatest chamber works ever written. And in the symphonic version, instead of one player on each part, the CSO strings resounded together in powerful lament. There was nothing maudlin about it. The effect was wrenchingly beautiful, the experience cathartic, and in its way a fitting memorial to the distinguished late conductor who had led his CSO colleagues in so many concerts at Orchestra Hall, at Ravinia, and throughout Europe and Asia on tour.

Although the Conlon-CSO concert lacked an intermission and was constructed to allow for sufficient spacing among musicians on the stage, there was little else that seemed like a concession to the pandemic. The program was a well-balanced wonder, not least because of the dazzling brilliance of Schubert’s Symphony No. 3, written by the composer at age 18, when he was a busy young Vienna free-lancer, teaching naughty schoolboys in his father’s school and composing songs and string quartets and masses and operas, too.

While it is well known that Mozart was a child prodigy of astonishing genius, surely this scintillating music Schubert wrote so quickly as a teen is evidence of similar wit, virtuosity and insight. Schubert had already assimilated Haydn whole and begun to write the singular songs that still appear on the recitals of singers on the preeminent stages. If you were at the concert, and the sound of John Bruce Yeh’s charming clarinet solo in Schubert’s first movement became an irresistible ear worm, on rewind for hours afterward in your head, you’re not alone.

The concert’s soloist was the pianist Alexander Gavrylyuk, a Ukrainian-born Australian virtuoso who had made his impressive CSO debut in 2018 performing Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto. This time he dove into Prokofiev’s brief but formidably virtuosic First Piano Concerto without seeming to break a sweat. All but austere in demeanor, Gavrylyuk was pure fire at the keys.

Indeed that contrast puts one in mind of the stories about Prokofiev, a rather sober herculean himself. The Chicago connection is significant here: It was his First Piano Concerto that Prokofiev performed with the CSO as a lanky 27-year-old in his 1918 Chicago debut. The young Russian was such a sensation at the time that the CSO booked him for the world premiere of another piano concerto, his third, in 1921. Thus it is that the CSO is commemorating this centennial with something of a Prokofiev festival: His Third Concerto is the focus of next week’s CSO concerts, Oct. 28-30, to be performed by the Russian virtuoso Denis Matsuev under the direction of Manfred Honeck.

Assuming Covid stays under control in weeks to come, Chicago Symphony Orchestra events soon will again resemble the traditional Orchestra Hall experience. When the CSO musicians perform the John Williams soundtrack to “Home Alone” during screenings for Thanksgiving weekend audiences, the expectation is that intermissions will resume.

It is wonderful to see the recognition of John Bruce Yeh’s singular skills that he has been sharing with us for more than 30 years. It is just too too bad that his candle, really his lamp, has been hidden under a bushel for so very long.