‘Il trovatore’ at the Lyric Opera of Chicago: Vital foursome re-energizes a Verdi classic

Jamie Barton is Azucena, the avenging daughter of a gypsy burned at the stake in Verdi’s ‘Il trovatore.’ The popular David McVicar production, in revival at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, is co-owned with the San Francisco Opera and the Met. (Production photos by Todd Rosenberg)

“Il trovatore” by Giuseppe Verdi at Lyric Opera of Chicago, through Dec. 9. ★★★★

By Nancy Malitz

With her little boy on her arm, the gypsy Azucena watches in horror as her mother is burned at the stake, wrongly accused of practicing witchcraft at the cradle of the second prince in the realm. In a fit of madness, Azucena snatches the little royal scion and tosses him onto the smoldering pyre. But when she looks down, she sees that she has grabbed the wrong boy. She has destroyed her own son.

What comes next is the subject of Verdi’s 1853 opera “Il trovatore,” which the great Italian composer envisioned as something of a female counterpart to his 1851 “Rigoletto,” about a crippled court jester whose vicious jokes put his own beloved daughter in deadly jeopardy. Verdi wrote it during the same hot streak, in his late thirties, that produced “Rigoletto” and “La traviata,” making him rich and famous.

When people talk about high-energy spectacle and romantic intensity in Italian opera, “Il Trovatore” is the classic Exhibit A. Instantly a hit when it opened in Rome, it remains one of the most frequently performed operas ever. Chicago’s Lyric Opera inaugurated its second season with it, back in 1955, with the fierce Neapolitan mezzo-soprano Ebe Stignani as the gypsy and Maria Callas in the heartbreaking soprano role. The current staging concept, masterminded by David McVicar, was a three-way commission by the Lyric, the Metropolitan Opera and the San Francisco Opera. All three companies have brought the production back repeatedly since 2006, when the Lyric first introduced it.

Gypsies strike their anvils while singing about hard work, good wine and gypsy women in the famous second act of ‘Il trovatore.’ a showpiece for chorus.

It’s still a winner, and to the credit of the revival director – Roy Rallo – McVicar’s “Trovatore” remains dynamic and fresh, from the flash and wham of gypsy smithies hammering away at their swords in the extravagant Anvil Chorus, to the tragic love triangle that complicates a civil war unfolding.

The casting requires a strong quartet of four different voice types at the core: the dramatic mezzo-soprano Azucena, the voluptuous soprano Leonora, and the two rivals who do not know they are brothers – the tenor Manrico, a troubador who is Azucena’s “son,” and his older brother, the baritone Count di Luna.

The dynamics of this volatile quartet of players can be tipped by casting. This Lyric production offered a robust foursome colored by a more touching and vulnerable Count di Luna than is often seen. The Polish baritone Artur Ruciński, in his impressive Lyric Opera debut, came off as a tyrant, sure, but one genuinely in love and given to reflection. There’s a curtain halfway through the show which is preceded by his soliloquy of wounded pride; he thinks that he has vanquished Manrico and cleared the way to win Leonora, only to discover that she is grief-stricken over Manrico’s apparent death and will enter a convent. The Count vows to kidnap her, as he knows he can. But his beautifully nuanced aria, “Il balen del suo sorriso” (The flash of her smile) made it clear this sovereign would prefer that love itself do the trick. Ruciński brought the mid-point curtain down with stakes still high.

The dynamics of current events can influence an opera’s reception, too. Verdi knew a thing or two about a people divided; his operas are threaded with songs reflecting his despair that the Italian language alone wasn’t enough to unite a peninsula that was mercilessly carved up, with pieces of what we now think of as Italy belonging to the French and Austrian empires in the north, a cluster of powerful dukedoms in the center, and additional kingdoms headquartered in Sardinia and Sicily that controlled big chunks of the south. Verdi’s own birthplace, Bussetto, changed hands. McVicar’s production, which has been seen in Chicago several times before, updates the time period to Verdi’s century; the audience is greeted with a curtain showing the disilusioned, howling faces of ordinary people in a detail from Goya. The image was jolting, almost painfully fresh this time around; its memory persists.

At the center of the “Trovatore” story is Azucena, sung here by Jamie Barton, an impressive, 37-year-old with a voice of steadfast strength and only a few Azucenas under her belt (Cincinnati and Munich) although there are doubtless many more in the offing. Azucena’s early scene at the gypsy camp is a tour de force; Manrico listens as she relives her horror at the crowd’s delight in her mother’s immolation, then dissolves into viscerally thrilling madness as she forgets herself, revealing the truth Manrico does not know, which forces her to quickly recover and dissemble. There is realism in Barton’s insightful reading of this self-made human horror. She has survived her losses and grotesquely doubled down. Wait for that cry of sick victory, which finally comes at the end of yet another war that no one wins.

As star-crossed lovers, tenor Russell Thomas and soprano Tamara Wilson become sadder and wiser quickly, but not without singing gloriously about it. Thomas’ “Di quella pira,” in which he vows to rescue his mother even though he knows it’s a trap set by the Count, was the stratospheric show-stopper one always hopes for.

Star-crossed Leonora (soprano Tamara Wilson in her Lyric debut) and Manrico (Russell Thomas) heroically strive against impossible forces set in motion long ago.

Wilson is possessed of buoyant musicality and a voice that’s rich and abundant at the top, even in delicate passages. Although she is young dramatically in the role, she was riveting at the height of an early scene, when she sang “Tacea la notte,” telling her companion Inez (the wonderfully skeptical contralto Lauren Decker) of her joy at being serenaded by a secret love (Manrico), who “made the earth seem like paradise.” A late scene of Leonora’s self-poisoning adds gravitas, as the nature of the disheveled woman’s full bargain with the Count becomes apparent.

There were surprises, though not from the chorus, whose participation in the gypsy camp Anvil Chorus scene was every bit the sonic spectacle desired. Conductor Marco Armiliato, whom I have often heard at the Met and the Lyric, seemed on automatic pilot in certain stretches, with beat-heavy stage-to-pit coordination putting the grace of the initial musical flow in jeopardy. Charles Edwards’ revolving unit set, with its tall, forbidding walls that rotate for different looks, now comes off retro rather than modern, although the unidentified charred body, hanging from a pole line, remains as startling and disturbing as ever.

The debut of Italian bass Roberto Tagliavini marks him as a terrific Verdi singer and a wonderful find; he’s the captain of the guard who relates current events (and the gypsy’s back-story) for the soldiers’ benefit, and ours. I hung on every note of that cameo.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

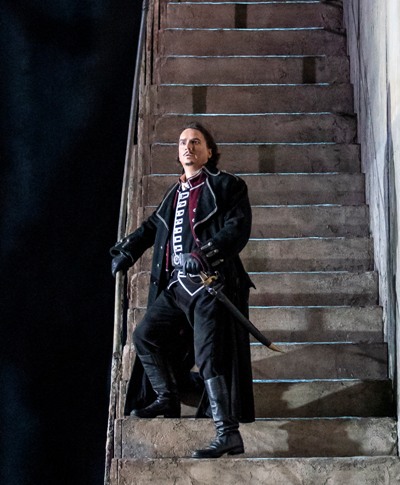

In his Lyric debut, bass Roberto Tagliavini (red waist) entertains the troops with the story of a gypsy once burned at the stake for casting a spell on an infant of the noble household.

Tags: Artur Rucinski, Charles Edwards, David McVicar, Il trovatore, Jamie Barton, Lauren Decker, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Marco Armiliato, Roberto Tagliavini, Roy Rallo, Russell Thomas, Tamara Wilson, Verdi