Directorship extended, Muti returns to CSO with Mozart, fresh commitment, higher goals

Interview: On the orchestra’s recent tour, Riccardo Muti reflected on the state of the CSO, his vision for next four years and his legacy.

By Nancy Malitz

Italian maestro Riccardo Muti is back in town and eager for another dive into Mozart with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Chicago and Wheaton March 15-17. The program, which features Mozart’s “Linz” Symphony (his 36th) and a duo turn by concertmaster Robert Chen and guest soloist Paul Neubauer in Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante, fits right into the CSO music director’s primary artistic goals.

When Chicago On the Aisle caught up with Muti in February, on a morning between two Carnegie Hall concerts by the CSO, he was relaxing in his New York hotel suite and musing on the significance of a two-year extension that prolongs his responsibility to the orchestra through August 2022.

When Chicago On the Aisle caught up with Muti in February, on a morning between two Carnegie Hall concerts by the CSO, he was relaxing in his New York hotel suite and musing on the significance of a two-year extension that prolongs his responsibility to the orchestra through August 2022.

Muti made it clear the job is about more than conducting alone. He pronounced himself ready to take on the work of keeping the 127-year-old orchestra whole, fit, and facing its future.

At 76, lithe and confident, the cosmopolitan maestro seemed energized rather than exhausted by the rigors of the eight-concert, five-city CSO East Coast tour that included stops in the nation’s capital and southern climes in addition to the obligatory performances in the nation’s musical mecca.

Muti’s contract will bring his commitment to 12 full seasons as music director, no small portion of an artist’s life in this age of jet-setting options. If it does not add up to Frederick Stock’s quite extraordinary 37-year tenure that commenced back in 1905, or Georg Solti’s 21 seasons, it will exceed the length of Fritz Reiner’s celebrated decade back in the legendary Fifties.

Muti’s contract will bring his commitment to 12 full seasons as music director, no small portion of an artist’s life in this age of jet-setting options. If it does not add up to Frederick Stock’s quite extraordinary 37-year tenure that commenced back in 1905, or Georg Solti’s 21 seasons, it will exceed the length of Fritz Reiner’s celebrated decade back in the legendary Fifties.

“When I was asked to extend, I said it’s best to think of two more years only (for a total of four) because you never know at what point your health – or becoming even more homesick! – might be a problem,” Muti recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t want to jeopardize.’ I said that two years would be fine, and that in any case I would remain connected with the orchestra if they wanted me to do concerts or think about special projects for the future.”

“When I was asked to extend, I said it’s best to think of two more years only (for a total of four) because you never know at what point your health – or becoming even more homesick! – might be a problem,” Muti recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t want to jeopardize.’ I said that two years would be fine, and that in any case I would remain connected with the orchestra if they wanted me to do concerts or think about special projects for the future.”

He sympathized with the brutal constraints of any major orchestra that hopes to compete for a music director against the clock; the right candidate may not even exist within the given window, and if such an elusive opportunity should become available, it is as a spark that, as Muti put it, “burns in so short a time.”

“So I said that I would like to defend and protect them for two more years,” he said. “We are almost ten years now since I began in Chicago as a guest conductor, and it has always been a beautiful musical understanding between us, so I do feel the responsibility of this orchestra concerning its future. For such a great orchestra, you need not only an important conductor but somebody who knows the repertoire, who has charisma, and who is internationally established so that when an orchestra goes on tour they have full houses. No one is indispensable, but it is not easy to find the musician who will carry the orchestra to a higher level and also keep it there so that it remains at the top three or four.“

In that regard, a key responsibility for Muti and his orchestra committee is the job of keeping the CSO whole, with key orchestral positions filled and well matched, including a top-flight quartet of woodwinds – oboe, flute, clarinet and bassoon – as well as principal horn, principal trumpet and so on. Twenty-two musicians have been appointed under Muti’s watch, including eight eminent principal players – among them timpanist David Herbert, clarinetist Stephen Williamson, bassist Alexander Hanna and bassoonist Keith Buncke.

Yet one star player seems to arrive as another unfortunately leaves. When flutist Mathieu Dufour left for the Berlin Philharmonic and was replaced by Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson, from the Metropolitan Opera, everybody was happy all around in fairly short order. But it doesn’t always go that smoothly. Auditions don’t always result in hires. Open seats have lingered in the spotlighted solo positions of principal oboe, trumpet and horn.

Yet one star player seems to arrive as another unfortunately leaves. When flutist Mathieu Dufour left for the Berlin Philharmonic and was replaced by Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson, from the Metropolitan Opera, everybody was happy all around in fairly short order. But it doesn’t always go that smoothly. Auditions don’t always result in hires. Open seats have lingered in the spotlighted solo positions of principal oboe, trumpet and horn.

“We need to get the positions filled,” Muti said. “This may be easy enough in other orchestras, but here you really have to have the stars. And the sound has to fit. What works as first oboe in the Vienna Philharmonic is not a match for Chicago. It would be one sock left and a different sock right. I want to know that when I go I have left a great player – the right player, and a good person, not a prima donna, someone that makes good harmony –in each of those positions.”

The Mozart that Muti is now conducting also remains essential to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s further development, he believes. When asked about what composers he might want to focus on in the years ahead, he immediately brought up Mozart, and also Beethoven, but then Mozart again. While it is often said that Mozart is the first great love of all children learning the piano, and that Mozart remains every music lover’s oldest friend, it is also likely that what Muti brings out in this composer will strike American listeners as something new.

The maestro’s perspective involves (wait for it) Italy. And if you are now chuckling, it is doubtless because you have heard Muti, who is Neapolitan through and through, making affectionate remarks about his native culture on any number of occasions in spontaneous podium-side chats. But on this point of Mozart, Muti is making a serious and striking argument, derived from a subtly different artistic discipline that rests on special ground. The great majority of Mozart interpreters come from an experience saturated in the Austro-German tradition of Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms and Wagner. Muti is singularly situated to see another line.

Mozart himself was intimately familiar with the lyrically pulsating Neapolitan school that stretches from Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) to Niccolò Jommelli (1714-1774), Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816), Domenico Cimarosa (1749-1801) and would culminate after Mozart’s time in Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870). For American music lovers today, these are textbook names that recall, at best, a short piece or two.

Mozart himself was intimately familiar with the lyrically pulsating Neapolitan school that stretches from Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) to Niccolò Jommelli (1714-1774), Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816), Domenico Cimarosa (1749-1801) and would culminate after Mozart’s time in Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870). For American music lovers today, these are textbook names that recall, at best, a short piece or two.

But these were composers that nurtured the young Mozart. He traveled to Naples while still a teen, in the company of his father, who was keen to increase the boy’s fame among the powerful nobility. While in Naples, Mozart met Jommelli and later sent him some of his own music on similar texts by way of homage to his illustrious senior. Muti underscored that Naples was a citadel of central importance in those days, closely aligned with Vienna: Maria Carolina the queen of Naples, was Austrian royalty, an older sister to Marie Antoinette.

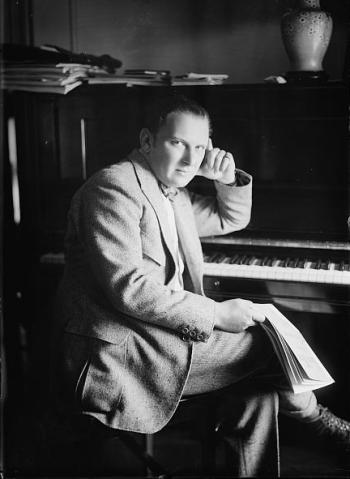

To demonstrate the Neapolitan roots that nurtured the young composer, Muti offers an excellent short video excerpt of a lecture that Muti delivers extempore, while seated at the piano, on Cimarosa’s opera “The Return of Don Calandrino.”

To demonstrate the Neapolitan roots that nurtured the young composer, Muti offers an excellent short video excerpt of a lecture that Muti delivers extempore, while seated at the piano, on Cimarosa’s opera “The Return of Don Calandrino.”

It’s from an eight-DVD set of rehearsals and piano lectures, with English subtitles, in collaboration with the Cherubini Youth Orchestra, which Muti founded. The four-and-a-half minute clip shows Muti going back and forth between the influential Neapolitan Cimarosa’s plausible evocation of flowing waters, and Mozart’s transformation of the same idea into the twinkle of something utterly magical.

“Mozart is the composer that the big American orchestras have the most difficulty with stylistically,” said Muti, who is proud of the singing quality that the CSO achieves, even as he encourages more – an apotheosis of pure song that is not necessarily operatic.

“Mozart is the composer that the big American orchestras have the most difficulty with stylistically,” said Muti, who is proud of the singing quality that the CSO achieves, even as he encourages more – an apotheosis of pure song that is not necessarily operatic.

Mozart highlights coming up later this season include a splendid stand-alone Kyrie on a June 21-24 program with a line-up of powerhouse singers that includes the soprano Krassimira Stoyanova, mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Gubanova, tenor Dmitry Korchak and bass-baritone Eric Owens.

In the second week of season-openers next fall, Sept. 27-29, one can look forward to Mozart’s Overture to “Don Giovanni” and the beloved Symphony No. 40 on Sept. 27-29.

That is followed by the Oct. 6 Symphony Ball, with Muti mingling Austro-German and Italian favorites such as Strauss waltzes and Puccini’s Intermezzo from “Manon Lescaut,” along with Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, performed by French pianist David Fray, who is Muti’s son-in-law. The concerto has a sublime second movement of melodic purity, and the lively finale has breakthrough ideas of all kinds.

“Robert Schumann used to say that if Mozart were a shoemaker, he would make shoes that everybody could wear. But that composers of Schumann’s own time were making shoes not everybody could wear. I feel the same way about music today. Mozart is like Shakespeare. He is universal. Everybody still understands Mozart.”

Related Links:

- Muti extends CSO directorship for two years, and orchestra announces plans for 2018-19: Read about it at Chicago On the Aisle

- CSO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall were grand, but splendor also was writ small – in encores: Read about it at Chicago On the Aisle