‘Saw My Neighbor on the Train’ at Redtwist: Amid pain and plain talk, generations collide

Review: “I Saw My Neighbor on the Train and I Didn’t Even Smile” by Suzanne Heathcote, at Redtwist Theatre through Dec. 18 ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Just when you think you’ve seen the ultimate dysfunctional family on stage, along comes Suzanne Heathcote’s gritty play “I Saw My Neighbor on the Train and I Didn’t Even Smile,” a stunner that touches a core of hope in a mesmerizing production at Redtwist Theatre.

Sadie is an unmoored teen whose latest cry for attention takes the form of a sex video she made with two guys at her school. With Sadie needing to find another school, her loser of a dad, who’s about to fly off to Hawaii to get married (again), prevails upon his sister to take the girl in – just for a while.

The sister, now a year into grieving over the death of her dog, is in therapy. No wonder; wait till you meet her mom, a formidable, unfiltered piece of work who knows only two kinds of talk: plain and plainer. And off we go, as the defiant girl, her overwhelmed aunt and unvarnished grandma collide like bumper cars at a carnival. At least nothing is left unsaid.

The sister, now a year into grieving over the death of her dog, is in therapy. No wonder; wait till you meet her mom, a formidable, unfiltered piece of work who knows only two kinds of talk: plain and plainer. And off we go, as the defiant girl, her overwhelmed aunt and unvarnished grandma collide like bumper cars at a carnival. At least nothing is left unsaid.

Here is ensemble acting at its volatile best, and seriously close-up. But in-your-face proximity describes any night of theater in Redtwist’s tiny performing space, where anyone sitting in the front row needs to keep feet tucked back lest they trip an actor – and pretty much everyone’s sitting in the front row. And this encounter seemed particularly immersive.

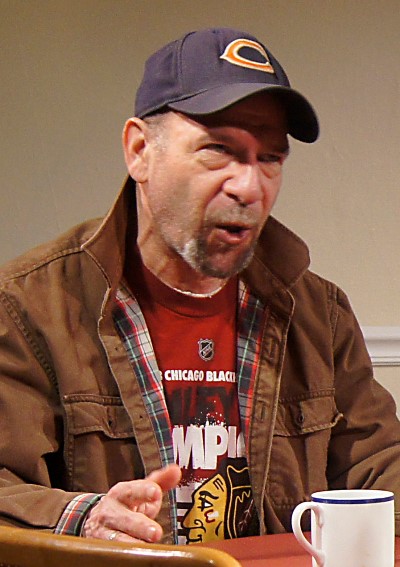

I was maybe three feet from Adam Bitterman’s desperate, pleading, wheedling Jamie (the girl’s dad) at a coffee shop as he tries every appeal in the book to get his sister Rebecca (Jacqueline Grandt) to look after Sadie so he can go through with his far-off wedding. I could have poured refills for them. But I’m pretty sure Bitterman’s single-minded Jamie was unaware of anyone else in the room except gentle Rebecca, now giving it her all not to get snookered again by her brother’s sweet-talking cons.

When he offers her money, Rebecca points out that he still owes her from an old loan. Is that what this is about? Jamie exclaims, visibly wounded. He’s very good at the game. Bitterman delivers the pitch so persuasively that you forget, even in this first scene, that it’s an actor holding forth an arm’s length away. When Jamie plays his winning card, it’s drawn from the bottom of the deck and etched with a scene from their childhood.

When he offers her money, Rebecca points out that he still owes her from an old loan. Is that what this is about? Jamie exclaims, visibly wounded. He’s very good at the game. Bitterman delivers the pitch so persuasively that you forget, even in this first scene, that it’s an actor holding forth an arm’s length away. When Jamie plays his winning card, it’s drawn from the bottom of the deck and etched with a scene from their childhood.

So troubled Sadie shows up at Rebecca’s door. Emma Maltby’s portrayal of the angry teen is steeped in pain, petulant, withdrawn. But the girl is received by Grandt’s vulnerable and empathic Rebecca with kindness and her best effort to help Sadie feel at home. And then in plows Daphne, Grandma the road-grader: Kathleen Ruhl in an unflinching turn that alone might justify the price of a ticket.

If Daphne owns a lexicon, the page with the word subtle has been removed. She lubricates her bruising directness with a constant drizzle of hard liquor, and she is not selective about the objects of her clear counsel or untrimmed rebuke. The striking thing about Ruhl’s bazooka salvos is that she unleashes them as mere matter-of-fact observations – seldom without edge, but never in the heat of rancor. It’s just that in Daphne’s eyes, a spade is not, ever, an implement of husbandry. Ruhl’s tough old gal isn’t cruel – well, not willfully so; just routinely mortifying.

But there’s also beauty in Ruhl’s performance. It wells up in a scene where she discovers something very old that she holds in common with Sadie – and then it slips away, and with it that leathery veneer. The moment is fleeting, but the truth is profound and affecting.

It is the slow but credible convergence of these three souls, women of three generations, that gives the play its purpose and attraction. Grandt’s emotionally reeling Rebecca, in early middle age and single, would like to date but doesn’t know where to turn. Sadie offers a couple of constructive tips. In her prickly fashion, Daphne sees the good her daughter and the hurting teen are doing for each other.

It is the slow but credible convergence of these three souls, women of three generations, that gives the play its purpose and attraction. Grandt’s emotionally reeling Rebecca, in early middle age and single, would like to date but doesn’t know where to turn. Sadie offers a couple of constructive tips. In her prickly fashion, Daphne sees the good her daughter and the hurting teen are doing for each other.

Into the mix drops Eric, Sadie’s new classmate and a math whiz (the earnestly nerdy and warmly engaging Joshua Servantez). When the two begin working on a math project together, Eric quickly sees that the rebellious girl is something more than her brash self-portrait.

It would be wrong to suggest that all ends well. Sadie’s suffering is real and deep, and director Erin Murray allows it to resonate in Redtwist’s tiny space. But if her dad appears to be irredeemable, Sadie is not. As for her aunt, Rebecca, well, she saw that nice man, her neighbor, on the train and she’s beaming with romance. It is Ruhl’s crusty Daphne, of course, who has the last word on that.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Adam Bitterman, Emma Maltby, Erin Murray, Jacqueline Grandt, Joshua Servantez, Kathleen Ruhl, Redtwist Theatre, Suzanne Heathcote

1 Pingbacks »