Role Playing: Joel Reitsma drew moral profit from banker-captor clash of ‘Invisible Hand’

Interview: In Steep Theatre’s intimate box, the actor says, Ayad Akhtar’s intense play gains edge from the audience. Thru Nov. 18.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Joel Reitsma creates a convincingly distressed investment banker who parlays his expertise into a desperate, life-preserving deal with his Pakistani captors in Ayad Akhtar’s “The Invisible Hand” at Steep Theatre. But Reitsma admits up front that he knows little about the trading game; and besides, he’s quick to add, the play isn’t about the stock market anyway. It’s about the corrosive power of money.

“When you start with any character in any story, you don’t know anything – their life, what they find interesting, what they hate,” says Reitsma. “You have to draw those things out from the things they say, the decisions they make, the things they turn away from.

“When you start with any character in any story, you don’t know anything – their life, what they find interesting, what they hate,” says Reitsma. “You have to draw those things out from the things they say, the decisions they make, the things they turn away from.

“I have no idea how to do any of that financial stuff, and that’s not where I started – by learning about options. Honestly, that’s not what the play is about. I wanted to know what was happening between this American and his Pakistani captors. I wanted to understand the dynamic between them – the power plays, the anger, the fear and the frustration.”

In the play’s setup, the American banker Nick, working in Pakistan, has been swept off the street by some locals who believe they can ransom him for $10 million – money needed to help relieve the severe privation of their countrymen. Nick has been isolated in a cell where he sees no one but a young guy called Dar (played by Anand Bhatt), who attends to his daily needs; his primary inquisitor, Bashir (Owais Ahmed), and the controlling Imam (Bassam Abdelfattah).

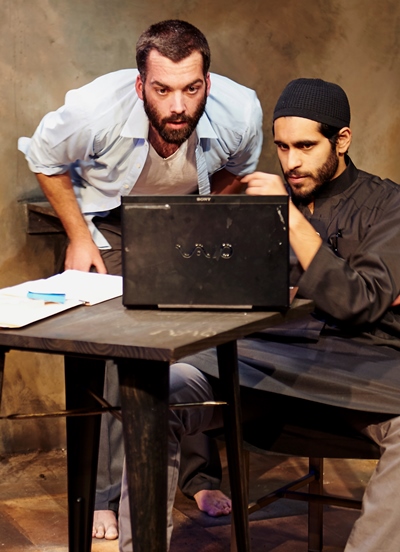

Nick tells the Pakistanis there’s no way he can raise $10 million, but maybe he can put together three. No dice, his captors reply: It’s $10 million or Nick will die. That’s when the terrorized banker hits on the idea of working off his ransom. If the Pakistanis will advance him some seed money to invest, he can generate a substantial return, then keep reinvesting until, over a period of a few years, he will amass the cash they demand and earn his freedom. All from a laptop that Nick will not be allowed to touch, but which Bashir will operate on his orders.

At the outset, Nick cautions the Pakistanis that wealth can be addictive. Acquire a little, get that taste, and you want more. It’s not long before Nick’s investments start bringing in big bucks, and his captors – God-fearing men for whom millions of dollars was once just a formless concept – find their heads turned by the comely glisten of mammon. And meanwhile, the Pakistanis’ life-or-death power over Nick is mitigated by the high-profit magic their captive displays again and again. Who’s in control of whom?

At the outset, Nick cautions the Pakistanis that wealth can be addictive. Acquire a little, get that taste, and you want more. It’s not long before Nick’s investments start bringing in big bucks, and his captors – God-fearing men for whom millions of dollars was once just a formless concept – find their heads turned by the comely glisten of mammon. And meanwhile, the Pakistanis’ life-or-death power over Nick is mitigated by the high-profit magic their captive displays again and again. Who’s in control of whom?

“As Nick establishes his value to these other characters, an us-against-them power dynamic emerges,” says Reitsma, adding that he and director Audrey Francis “went back and forth about this, how we get into each other’s faces. He’s not physically strong, he can’t organize a coup, but they want money, which means they don’t want to kill him. Once you’ve established that value – and there are several points in the play where Nick realizes they aren’t going to kill him – you can risk push-back.

“But Nick’s still in great danger. He’s their prisoner, and when they remember that they are the ones in control, you see the power shift back. It’s really helpful that the whole play happens in that little room. Audrey is a director who knows how to play relationships. She didn’t prescribe to us who should be in charge at any given moment, who should be angry – or pushing. She would just say to any of us, ‘He’s pushing you right now. How does that make you feel? So the really intense scenes were charged with very realistic reactions.”

The larger result, Reitsma says, is that because of subtle shifts in the way characters feel and interact, no two performances are alike: “That makes the play so exciting to do. We’re all watching it grow. I think we should be surprised by relationships, especially when people are from two completely different cultures. They find commonalities, butt heads and experience events that bring them closer together.

The larger result, Reitsma says, is that because of subtle shifts in the way characters feel and interact, no two performances are alike: “That makes the play so exciting to do. We’re all watching it grow. I think we should be surprised by relationships, especially when people are from two completely different cultures. They find commonalities, butt heads and experience events that bring them closer together.

“At the beginning of this play, Nick and Bashir hate each other. Nick looks down on Bashir for his bull-headedness and his romanticized view of revolution. But then Bashir shows that he is capable of so many things, and the moment comes when their relationship shifts. It goes from captive-captor to teacher-student, big and little brother, father-son and ultimately feuding friends.”

Even if for Nick the relationship with Bashir remains essentially adversarial and perilous to the very end, says Reitsma, “it’s really cool how Akhtar has structured this.”

Nick and Bashir, personifications of radically different cultures, not only end up mutually respectful, says Reitsma: They also give each other “gifts.”

“Nick’s gift to Bashir is knowledge and a new sense of self-worth,” the actor says. “He tells Bashir, ‘You are a smart person, you are capable.’ It’s the gift a mentor gives his student. Bashir gives Nick many things that students give their teacher, especially the satisfaction of seeing a passion ignited. But there are small things, too, like reports from the outside and info that’s hard to get.”

Ultimately, says Reitsma, we get the story from Nick’s perspective: a white, privileged Westerner thrust into a culture he doesn’t understand.

Ultimately, says Reitsma, we get the story from Nick’s perspective: a white, privileged Westerner thrust into a culture he doesn’t understand.

“Nick is forced into a situation where he has to learn about the Other. For me as an actor, it’s about the arc of relationships. That’s the biggest eye-opener. There’s so much going on, so many moving pieces. If you graphed it all out, it’s like watching stocks, value, power go up and down. That’s what’s fascinating about this play.”

And then there’s the compression factor: the confined black-box that is Steep Theatre.

“The audience is inches away from action that may or may not make viewers comfortable,” says Reitsma. “But it cuts both ways. As actors, we experience pin-drop silence or side conversations, which we hear. It can be a distraction or a motivation. With this story, the extreme intimacy works so well because it underscores what is happening to one person, and to a whole country. In a larger house, you can pull away at any time. At Steep, you can never feel separated. You’re in that cell with Nick and his captors. You’re right there for the ride.”

Related Links:

Review of “The Invisible Hand”: Read it at Chicago On the Aisle

More Role Playing Interviews:

- Lawrence Grimm found Lincoln first in pages of history, then within himself

- Cristina Panfilio spreads wings she didn’t know she had as midsummer Puck

- Tyla Abercrumbie was set to run little ‘Hot Links’ café, but why was she there?

- AnJi White, as Catherine Parr, learned to keep her wits – to keep her head

- Adam Bitterman, unlikely florist in ‘Seedbed,’ dug deep to create a rare bloom

- Danny McCarthy, pushing broom in ‘The Flick,’ finds vital pulse in long silences

- Mierka Girten, actor with MS, knows wound behind her character’s scars

- Sandra Marquez, as Clytemnestra, sees an exceptional woman in the Greek queen

- Brian Parry says he summoned courage before wit as George in ‘Virginia Woolf’

- Tracy Michelle Arnold debunks madness as force that drives Blanche DuBois

- Christopher Donahue, as Ahab, finds sea’s depth in sadness of a vengeful soul

- Lance Baker embodies ennui, despair of fugitive Jews in ‘Diary of Anne Frank’

- Francis Guinan embraces conflict of father who fled from grim truth in ‘The Herd’

- Sophia Menendian reached back (but not far) as plucky Armenian refugee of 15

- Lindsey Gavel’s distressed Masha, in ‘Three Sisters,’ began with a touch of cheer

- Hollis Resnik felt personal bond with zealous, skeptical scholar in ‘Good Book’

- A.C. Smith is ready undertaker, lord of diner world in ‘Two Trains Running’

- Lia D. Mortensen’s intense portrait of a mentally failing scientist holds mirror to life

- Siobhan Redmond sees re-formed Lady Macbeth as valiant queen in ‘Dunsinane’

- Eileen Niccolai harnessed a storm of emotions to create spark in Williams’ Serafina

- Steve Haggard, aiming at reality, strikes raw core of grieving man in ‘Martyr’

- Shannon Cochran found partners aplenty in sardonic, twice-told ‘Dance of Death’

- Natalie West scaled back comedy to nail laughs, touch hearts in ‘Mud Blue Sky’

- Dave Belden, actor and violinist, adjusted pitch for ‘Charles Ives Take Me Home’

- Joseph Wiens starts at full throttle to convey alienation of ‘Look Back in Anger’

- Shane Kenyon touches charm and hurt of lovable loser in Steep’s ‘If There Is’

- Ramón Camín sees working class values in Arthur Miller’s tragic Eddie Carbone

- Hillary Marren’s charming, rapping witch in ‘Woods’ shapred by hard work, free play

- Mary Beth Fisher embraces both hope, despair of social worker in ‘Luna Gale’

- Brad Armacost switched brothers to do blind, boozy character in ‘The Seafarer’

- Karen Woditsch shapes vowels, flings arms to perfect portrait of Julia Child

- Ora Jones had to find her way into Katherine’s frayed world in ‘Henry VIII’

- Kareem Bandealy tapped roots, hit books for form warlord in ‘Blood and Gifts’

- Eva Barr explored two personas of Alzheimer’s victim to find center of ‘Alice’

- Darrell W. Cox sees theater’s core in closed-off teacher of ‘Burning Boy’

- Chaon Cross turned Court stage into a romper room finding answers in ‘Proof’

- Dion Johnstone turned outsider Antony to bloody purpose in ‘Julius Caesar’

- Noir films gave Justine Turner model for shadowy dame in ‘Dreadful Night’

- Anish Jethmalani plumbs agony of good man battling demons in ‘Bengal Tiger’

- Gary Perez channels his Harlem youth as quiet, unflinching Julio in ‘The Hat’

- Kamal Angelo Bolden sharpened dramatic combinations to play ‘The Opponent’

- In wheelchair, Jacqueline Grandt explores paralysis of neglect in ‘Broken Glass’

- James Ridge thrives in cold skin of Shakespeare’s smiling serpent, Richard III

- Stephen Ouimette brews an Irish tippler with a glassful of illusions in ‘Iceman’

- Ian Barford revels in the wiliness of an ambivalent rebel in Doctorow’s ‘March’

- Chuck Spencer flashes a badge of moral courage in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Price’

- Rebecca Finnegan finds lyrical heart of a lonely woman in ‘A Catered Affair’

- Bill Norris pulled the seedy bum in ‘The Caretaker” from a place within himself

- Diane D’Aquila creates a twice regal portrait as lover and monarch in ‘Elizabeth Rex’

- Dean Evans, in clown costume, enters the darkness of ‘Burning Bluebeard’

- Dan Waller wields a personal brush as uneasy genius of ‘Pitmen Painters’

- City boy Michael Stegall ropes wild cowboy in Raven Theatre’s ‘Bus Stop‘

- Brent Barrett is glad he joined ‘Follies’ as that womanizing, empty cad Ben

- Sadieh Rifai zips among seven characters in one-woman “Amish Project”

- Kirsten Fitzgerald inhabits sorrow, surfs the laughs in ‘Clybourne Park’

- Janet Ulrich Brooks portrays a Russian arms negotiator in ‘A Walk in the Woods’

Tags: Anand Bhatt, Audrey Francis, Bassam Abdelfattah, Joel Reitsma, Owais Ahmed

1 Pingbacks »