Theater as crucible: Two Arthur Miller classics bridge high peaks of Goodman, Steppenwolf

Review: “A View from the Bridge” at Goodman Theatre thru Oct. 22. ★★★★★; “The Crucible” at Steppenwolf thru Oct. 21. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

If you have not yet seen both “A View from the Bridge” at Goodman Theatre and “The Crucible” at Steppenwolf Theatre – well, it’s Miller time.

These are mesmerizing productions of two of Arthur Miller’s finest plays, and impressive reminders of why Goodman and Steppenwolf hold such eminent places on Chicago’s – indeed, the nation’s – theater scene. Each of these parallel runs has only a handful of performances remaining. Together, they make for a stunning one-two theatrical punch.

“A View from the Bridge” is the existential tragedy of Eddie Carbone, a stand-up guy who works on the Brooklyn docks. Eddie (Ian Bedford) and his wife Beatrice (Andrus Nichols) have raised the daughter of her deceased sister. That makes the now grown girl, Catherine (Catherine Combs), something more than just Eddie’s niece. She’s essentially his daughter, and he’s devoted to her; he loves her. As Catherine has flowered into young womanhood, Eddie has grown increasingly protective of her. Yet the question comes ever more sharply into focus: What, exactly, is Eddie protecting her from?

“A View from the Bridge” is the existential tragedy of Eddie Carbone, a stand-up guy who works on the Brooklyn docks. Eddie (Ian Bedford) and his wife Beatrice (Andrus Nichols) have raised the daughter of her deceased sister. That makes the now grown girl, Catherine (Catherine Combs), something more than just Eddie’s niece. She’s essentially his daughter, and he’s devoted to her; he loves her. As Catherine has flowered into young womanhood, Eddie has grown increasingly protective of her. Yet the question comes ever more sharply into focus: What, exactly, is Eddie protecting her from?

In this stark take on the play, directed by Ivo Van Hove, events unfold within a minimal set (Jan Versweyveld) bordered by a wall at the rear and a continuous three-sided bench, effectively a boundary that hems in all the characters: a cage, from which no one can fly.

The fatal spark is set when two desperate cousins arrive from depression-riven Italy, illegals, whom Eddie and Beatrice will shelter while the men earn money on the docks to send back home. Anyway, that’s the solemn intent of one of them, Marco (Brandon Espinoza), whose wife and children are on the verge of starvation. But Marco’s younger brother Rodolpho (Daniel Abeles) regards the situation differently. He sees the American dream – nice clothes, nights on the town. He also sees Catherine, who returns his glances. And both are observed by Eddie, who doesn’t like the view.

Miller’s tightly wound drama is a memory play, told by a lawyer (Ezra Knight) who serves as both counsel to Eddie and our Greek chorus, spinning his sad commentary on the inevitable ruin. “A View from the Bridge” is also an elegantly wrought ensemble work, and this troupe of actors delivers it with searing edge, hot urgency. But in the end, the play depends on the rising tension incited by Eddie’s unnamable flaw, on the high contrast between his genuine goodness and the obsession that clutches him but which he cannot comprehend.

Miller’s tightly wound drama is a memory play, told by a lawyer (Ezra Knight) who serves as both counsel to Eddie and our Greek chorus, spinning his sad commentary on the inevitable ruin. “A View from the Bridge” is also an elegantly wrought ensemble work, and this troupe of actors delivers it with searing edge, hot urgency. But in the end, the play depends on the rising tension incited by Eddie’s unnamable flaw, on the high contrast between his genuine goodness and the obsession that clutches him but which he cannot comprehend.

Bedford’s Eddie is magnificent, a grand figure imposing and powerful – the more piteous in his helpless exasperation. Something very wrong has invaded his household, and he wants to drive it away but cannot. Bedford articulates the pathos of an exposed soul, a mighty oak split by lightning from a private sky of darkness and storms and terror. It is a chilling performance, heart-rending, defining, memorable.

“The Crucible” dwells in another world, no less dark or awful but far more public. Lies are the operative force in this grim parody of the McCarthy era’s anticommunist witch hunts. Miller simply turns his mirror to the 1692 witch trials in Salem, Mass. Although Steppenwolf presents the production as part of its Young Adults series, the show’s seriousness, potency and rigorous brilliance will appeal to adults of any age.

In a very conservative religious community, where the preacher (the self-consciously pious Peter Moore) keeps his flock attuned to the threat of Satanic influences on every hand, several young girls venture into the woods one night to do some naughty stuff – brew a cauldron of potion, taste some blood, dance naked. That same preacher espies them doing all this – yes, well, yes, maybe the naked dancing, too. The misbehaving girls include his own daughter, who ends up in bad shape the next day – unresponsive, actually. The other girls deny everything. So a higher religious authority (Erik Hellman as the embodiment of gravitas) is summoned to get to the bottom of it all: to determine whether the girls have come under Satan’s spell.

In a very conservative religious community, where the preacher (the self-consciously pious Peter Moore) keeps his flock attuned to the threat of Satanic influences on every hand, several young girls venture into the woods one night to do some naughty stuff – brew a cauldron of potion, taste some blood, dance naked. That same preacher espies them doing all this – yes, well, yes, maybe the naked dancing, too. The misbehaving girls include his own daughter, who ends up in bad shape the next day – unresponsive, actually. The other girls deny everything. So a higher religious authority (Erik Hellman as the embodiment of gravitas) is summoned to get to the bottom of it all: to determine whether the girls have come under Satan’s spell.

In no time, this incident has engulfed the community. Self-serving lies beget wild accusations and recriminations, witnesses are summoned and they in turn – unwittingly – condemn not only themselves but others whose names they invoke as character witnesses for themselves. Dozens of good people are jailed and brought to “justice” with two options: confess to consorting with the devil or refuse and face the gallows.

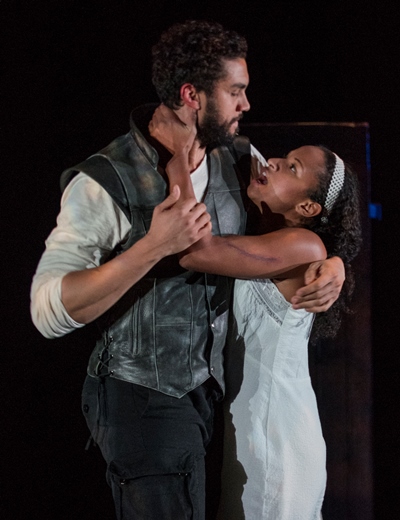

Amid the spite and vengefulness, the long arm of the law soon reaches the community’s model couple, John and Elizabeth Proctor (Travis Knight and Kristina Valada-Viars in performances of disarming grace and incredulity), who believe that the truth will set them free. Further complicating the fraught situation is the lust that the most audacious of the frolicking girls, Abigail (played with insidious determination by Naima Hebrail Kidjo), harbors for Proctor. They have in fact been lovers; but while Proctor has tried to put that indiscretion in the past, Abilgail pursues him.

As this crazed witch hunt intensifies, rumor substitutes for truth, and those who will not publicly confess to gross sin – a sudden interest in reading books, for instance – must pay the price of God’s justice, as construed by a high government official sent in as presiding judge and final authority.

As this crazed witch hunt intensifies, rumor substitutes for truth, and those who will not publicly confess to gross sin – a sudden interest in reading books, for instance – must pay the price of God’s justice, as construed by a high government official sent in as presiding judge and final authority.

It is Michael Patrick Thornton’s calm-and-fury as the judge that invokes the ultimate terror in this hair-raising production directed by Jonathan Berry. Thornton lends the judge an aspect of rational equanimity one moment, only to turn volcanic in his insistent piety the next – and the viewer realizes, with the poor souls on trial, that the outcome is preordained: To point, to intimate, to name is to convict.

Black arts, indeed. Arnel Sancianco’s severe period costumes and Izumi Inaba’s spare, dark set – made the more forbidding by Lee Fiskness’ lighting scheme – create an atmosphere in which even good cheer might be counted an offense, the devil’s infection. And we see what happens to citizens who cling to optimism and honesty, or trust in the redeeming powers of truth and innocence. In this crucible, a collective madness stands as the only truth, and it grinds innocence and rationality into a poison powder.

Related Links:

- “The Crucible” performance and ticket info: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- “A View from the Bridge” performance and ticket info: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Andrus Nichols, Arnel Sanciano, Arthur Miller, Brandon Espinoza, Catherine Combs, Daniel Abeles, Erik Hellman, Ezra Knight, Goodman Theatre, Ian Bedford, Izumi Inaba, Jan Versweyveld, Jonathan Berry, Kristina Valada-Viars, Lee Fiskness, Michael Patrick Thornton, Naima Hebrail Kidjo, Peter Moore, Steppenwolf Theatre, Travis Knight