‘The Rembrandt’ at Steppenwolf: Ruminating on the golden linkage of art and life and love

Review: “The Rembrandt” by Jessica Dickey. Directed by Hallie Gordon at Steppenwolf Theatre, extended through Nov. 11. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

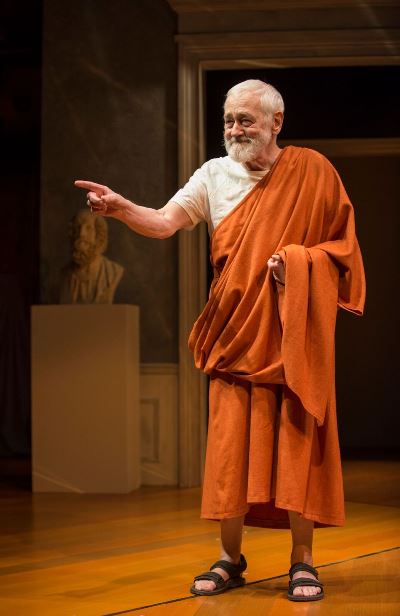

Jessica Dickey’s play “The Rembrandt” is a thing of great spiritual beauty, but Francis Guinan’s performance – you might say in the title role – at Steppenwolf Theatre bears out the imperative of another character in the play, Homer: that poetry must be spoken aloud. Guinan takes Dickey’s eloquent and insightful text to a transcendent place.

“The Rembrandt” is about connections – first, the way art connects with us, through the human link between painter and viewer. It is subtle, complicated, profound and ever changing, this humanistic pathway. We think of it as a one-way conduit: art touches us. But what if we were to touch the art – yes, literally, with an oily fingertip freshly greased with French fries from lunch? What would happen if we reached over that little rope boundary, when the guard wasn’t looking, and connected physically with, say, Rembrandt’s famous painting “Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer”?

“The Rembrandt” is about connections – first, the way art connects with us, through the human link between painter and viewer. It is subtle, complicated, profound and ever changing, this humanistic pathway. We think of it as a one-way conduit: art touches us. But what if we were to touch the art – yes, literally, with an oily fingertip freshly greased with French fries from lunch? What would happen if we reached over that little rope boundary, when the guard wasn’t looking, and connected physically with, say, Rembrandt’s famous painting “Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer”?

You’re thinking: Ah, I’ve seen this, on “The Twilight Zone.” A guy reaches out to a painting and, poof, becomes part of it. Nope. Dickey’s drama is made of far better stuff.

Henry (played by Guinan) is a sixtysomething guard at a major art museum, a veteran at his job and happy in the balance between meticulous procedure and the pleasure of watching the public enjoy the masterpieces he oversees. Yet his life is shadowed by the grave illness of his partner of some 35 years.

On this ordinary morning, Henry’s routine is disrupted by the arrival of a young man with a Mohawk and an attitude (Ty Olwin) on his first day of work as a new museum guard. He’s Henry’s trainee. This spunky youth, who goes by the name of Dodger, is an artist. Or, or as his puts it, an embellisher of public surfaces – by other lights, someone who defaces buildings. Dodger has just two questions for Henry: When is his first smoking break, and how does he move up in the organization?

On this ordinary morning, Henry’s routine is disrupted by the arrival of a young man with a Mohawk and an attitude (Ty Olwin) on his first day of work as a new museum guard. He’s Henry’s trainee. This spunky youth, who goes by the name of Dodger, is an artist. Or, or as his puts it, an embellisher of public surfaces – by other lights, someone who defaces buildings. Dodger has just two questions for Henry: When is his first smoking break, and how does he move up in the organization?

Also popping in – the museum’s public hours haven’t yet begun – is a twentyish girl, Madeline (Karen Rodriguez), who has come to copy a work for a class assignment. She is melancholy and a bit unsteady on her feet. She has recently lost someone dear to her, and she’s feeling rather lost herself.

Guinan’s long-experienced Henry takes these incursions in stride; indeed, in his precise and methodical fashion, he manages to fit the two irregularities into the routine of his early morning. Meanwhile, he gives the youngsters a casual lecture on the mystery and magic of art: No matter how often you experience a painting, it always holds something new – partly because you have changed since the last time you encountered it.

Gazing at Rembrandt’s portrait of Aristotle (which actually hangs in the Met Museum in New York), Henry notes the grand gold chain that falls around the philosopher’s cloak. It’s a symbol of life, its vitality and connectivity generation to generation, Henry explains: It is, arguably, the essential motif in this painting that depicts the great ancient thinker ruminating on the even older poet.

When Henry briefly leaves the room, Olwin’s brash Dodger urges Madeline to do the unthinkable: “Touch the painting!” When Madeline suggests that he’s out of his mind, he only repeats his command: “Touch the painting!” A shouting match ensues between this feisty pair, Olwin’s brassy insistence matched by Rodriguez’s unwavering incredulity: He’s like, “Touch the painting!” and she goes, “I won’t touch the painting!”

Then Henry comes back into the room, and practically the first words out of her mouth to him: “Touch the painting!”

Let’s just say Henry processes the idea. But when Act II begins, we aren’t in the museum anymore. We’re in 17th-century Amsterdam, where Guinan now portrays Rembrandt, with Rodriguez as his wife and Olwin as his adoring adolescent son. Watching Guinan’s gruff, slovenly painter, I couldn’t help thinking of Beethoven: this towering genius schlepping around his domicile – cleverly detailed by designer Regina Garcia – utterly dependent on someone else to keep order if any order is to be kept.

Let’s just say Henry processes the idea. But when Act II begins, we aren’t in the museum anymore. We’re in 17th-century Amsterdam, where Guinan now portrays Rembrandt, with Rodriguez as his wife and Olwin as his adoring adolescent son. Watching Guinan’s gruff, slovenly painter, I couldn’t help thinking of Beethoven: this towering genius schlepping around his domicile – cleverly detailed by designer Regina Garcia – utterly dependent on someone else to keep order if any order is to be kept.

Guinan shows us the genius with feet of clay, a worldly man whose habit of spending money as fast as he earns it distresses his son – but who keeps promising to reform, familiar vows that now fall on unbelieving ears. Yet he is a loving father and an appreciative spouse. Above all, however, he is a driven artist. He has a new commission from a wealthy man whom he holds in open contempt. Still, the artist does not despise his patron’s means. In his studio is a bust of Homer, and Rembrandt looks up to see his son musing on it, the lad’s hand resting on the plaster form.

The scene shifts, the Rembrandt household recedes and into view shuffles the old poet himself, his name enshrined in those two bulwarks of Western culture, “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.” John Mahoney looks like that bust of Homer made whole man. Advocate of his métier, Mahoney’s very human link in the oral tradition trumpets the inescapable necessity of poetry to be spoken, not read. The passion, the heart, the soul of verse resides in the speaking of it, he insists, in the direct communion between the inflected voice and the impressionable ear.

Homer in turn morphs, I won’t say how. But the play’s denouement is a gem. I will say that Henry the museum guard now has time on his hands, and he happily spends it at the bedside of his dying partner, also played by Mahoney. The two veteran actors make credible, indeed radiant, old consorts, spooning pudding together – a nice metaphor perhaps for spooning in a now lost use of the word. They abuse each other with a sharpness and delight available only to those who have loved long: who have mutually draped themselves with the golden chain of life.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheaterInChicago.com

Tags: Francis Guinan, Jessica Dickey, John Mahoney, Karen Rodriguez, Regina Garcia, Ty Olwin

This sounds like a marvelous, captivating work, based on other works of artistic genius. I would love to see this play with the extremely talented Francis Guinan and John Mahoney. Thank you for posting.