Dutoit sees a wide spiritual gamut before him in Easter weekend with Chicago Symphony

Preview: Conductor Charles Dutoit reflects on fare that will range from a feverish Honegger symphony to Fauré’s serene Requiem.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Musical reflections on Easter, transcendent and intimate and existential, form conductor Charles Dutoit’s multilayered theme for his concerts April 13-15 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The gentler parts are well known; for many listeners, however, the other part, a spiritual warp of upheaval and terror born of World War II, may come as revelation in startling terms.

For the second program of his two-week CSO residency, Dutoit has positioned as serene bookends Wagner’s Good Friday music from “Parsifal” and, with the Chicago Symphony Chorus, Fauré’s Requiem. Between these comes Arthur Honegger’s shattering – and yet mesmerizing – “Symphonie liturgique,” his Symphony No. 3, a purely orchestral work that really needs no words to convey its post-World War II amplitude of devastation and heartbreak and despair.

For the second program of his two-week CSO residency, Dutoit has positioned as serene bookends Wagner’s Good Friday music from “Parsifal” and, with the Chicago Symphony Chorus, Fauré’s Requiem. Between these comes Arthur Honegger’s shattering – and yet mesmerizing – “Symphonie liturgique,” his Symphony No. 3, a purely orchestral work that really needs no words to convey its post-World War II amplitude of devastation and heartbreak and despair.

“All the struggle of humanity is there,” says Dutoit. “Honegger was quite pessimistic. It is not a religious piece, contrary to what the title indicates. He used the (Latin) movement headings only in the sense of a creating a symphony. It’s essentially about the horror and stupidity of war.”

Those headings bespeak the episodes of a deeply painful tone poem. The first movement, marked “Dies irae” (Day of wrath), is grinding, abrasive, raw; the second movement (“De profundis clamavi” – from the depths we cry unto Thee) begins with an aura of resignation that quickly turns to mind-bending conflict; the finale, notes Dutoit, bears the paradoxical indication “Dona nobis pacem.”

“You hear those words — Give us rest – almost literally, pounded out by the orchestra: Doh – Nah – Noh – Bis – Pah – Chem. It’s the cry of crowds looking at the sky, looking for hope. And then, just at the end, Honegger offers that hope, that redemption.

“Honegger’s music has been close to me all my life. I studied with Ernest Ansermet and Charles Munch, who both knew him personally. I have always wanted to do the ‘Symphonie liturgique’ here, with this great orchestra.”

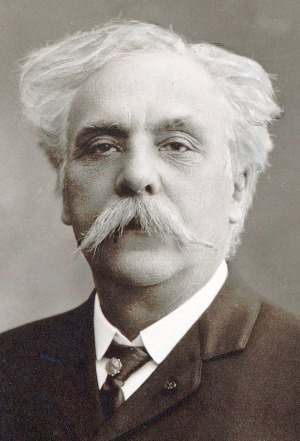

It wasn’t just one war but two that the Swiss-born Honegger (1892-1955) saw rip at very fabric and soul of Europe. Fauré (1845-1924) resided in a different world during the 1880s when he composed his serene and ever-beloved Requiem for orchestra, chorus, soprano (Chen Reiss) and baritone (Matthias Goerne). Through and through, the Requiem is as blissful as Honegger’s symphony is fraught.

“It’s like stained glass in a church,” says Dutoit of Fauré’s transparent and luminous Requiem. “It reminds me of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with all the colors that come out when the sun passes through its stained glass.

“Fauré’s Requiem isn’t modeled on the big, dramatic examples by Berlioz and Verdi. Fauré doesn’t even include the Dies irae.’ It isn’t contrapuntal, there are no fugues. It is the most peaceful music, beautiful. It wraps you in good feeling.”

Perhaps the closest thing to the Fauré is Brahms’ “German Requiem.” If they bear little resemblance stylistically, both are humanistic treatments of death, tender and reassuring and, not least, unmarked by theatricality.

Perhaps the closest thing to the Fauré is Brahms’ “German Requiem.” If they bear little resemblance stylistically, both are humanistic treatments of death, tender and reassuring and, not least, unmarked by theatricality.

“There is so much hope in Fauré’s setting,” says Dutoit. “It is above all of life’s struggles. It’s transparency is also exceptional, and that’s where it demands a top-flight chorus like this one. The singing must be very clean and clear, with no vibrato. I remember a great performance of Britten’s ‘War Requiem’ with the Chicago chorus a number of years ago, and I’ve long wanted to do the Fauré with them.”

Dutoit says he put this program together expressly in observance of Easter weekend, and so he will begin with Wagner’s Good Friday music, perhaps the most famous Easter music even penned that is not part of a specifically religious work.

“Good Friday is a very dark moment, three days before the Resurrection,” says the conductor. “In Rome, all the churches are blacked out and the statues are covered. Then, on Saturday evening at midnight, as you reach Easter Day, all the veils are removed and the light returns. I think that is the essence of Wagner’s radiant music. All oppression is gone. You breathe easily.”

Related Link:

- Performance and ticket info: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Charles Dutoit, Chen Reiss, Matthias Goerne