‘Bakersfield Mist’ at TimeLine: Drizzled paint points to Pollock, but is this $3 find for real?

Review: “Bakersfield Mist” by Stephen Sachs, produced by TimeLine Theatre at Stage 773 through Oct. 15. ★★

Review: “Bakersfield Mist” by Stephen Sachs, produced by TimeLine Theatre at Stage 773 through Oct. 15. ★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Maude is middle-aged, recently fired from her job as a bar tender and living alone in a dumpy trailer decorated with other people’s discarded junk. But one such piece of refuse is a painting that could be an original Jackson Pollock worth millions of dollars. That’s the starting point of Stephen Sachs’ play “Bakersfield Mist,” a two-hander at TimeLine Theatre starring a pair of Chicago’s best actors, who between them cannot bring this half-baked drama to much purpose.

The play’s title is a spin on an actual painting by Pollock, “Number 1, 1950” – also known as “Lavender Mist.” That work has a pivotal role by association as Sachs’ narrative unfolds.

The play’s title is a spin on an actual painting by Pollock, “Number 1, 1950” – also known as “Lavender Mist.” That work has a pivotal role by association as Sachs’ narrative unfolds.

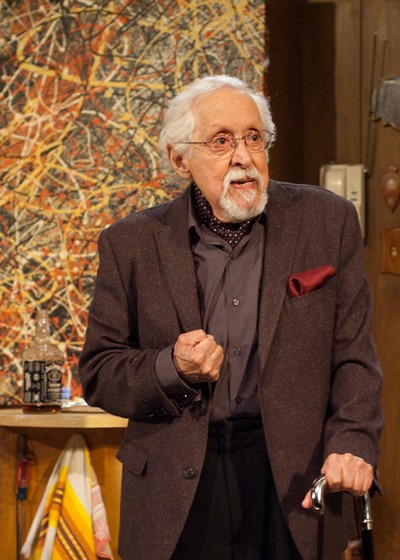

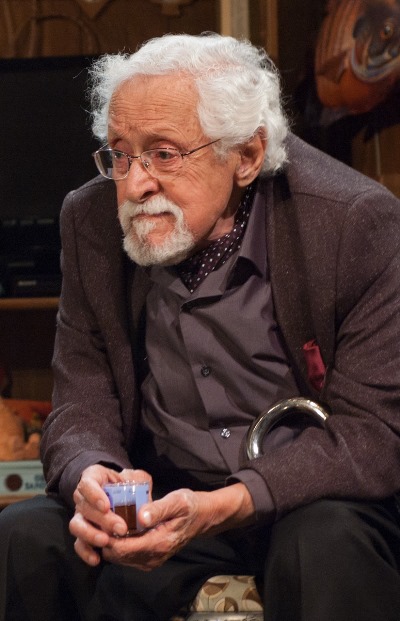

Told by a friend, a high school art teacher, that the painting she has picked up for three bucks – a large canvas covered with swirls of paint in many hues – well might be from Pollock’s own hand, Maude (Janet Ulrich Brooks) is on a mission to find an expert to certify the work’s authenticity. She reels in one of the art world’s preeminent authorities, Lionel Percy (Mike Nussbaum), who flies from New York to Bakersfield, Calif., where he is chauffeured to Maude’s trailer park to assess her acquisition.

After a terrifying encounter with a neighbor’s dog, the shaken art scholar reaches the safety of Maude’s trailer (tricked out in designer Jeffrey D. Kmiec’s funky trash-bin decor). It’s instantly clear that they are oil and water – or, closer to it, alcohol and tea. She is expansive, gritty, foul-mouthed and – what is the current phrase, poorly educated. He is uptight, arrogant, condescending and impatient to execute his assignment and be gone.

In terms of sheer physicality and tone, Brooks and Nussbaum are a funny mismatch – she overeager and he dusting a chair before venturing to sit down. They are indeed better than the playwright’s text, which among other problems belabors the haughty man’s ironic twists on Maude’s small talk: Banter along the lines of “I decorated the place myself” answered by “I find that easy to believe” is repeated six different ways, as if the playwright couldn’t refrain from just one more clever jibe.

Calculated effects damage the dialogue in various ways. At one point, Maude implores her arch, distant visitor to “be a person.” It’s a touching rhetorical gesture in a plausible moment. But mark it, because it will come back, less spontaneously and with much less conviction.

Calculated effects damage the dialogue in various ways. At one point, Maude implores her arch, distant visitor to “be a person.” It’s a touching rhetorical gesture in a plausible moment. But mark it, because it will come back, less spontaneously and with much less conviction.

Doubtful as we may be of Maude’s find, we are on her side. Before she brings out the mysterious painting, she just has to ask the question any of us might ask: What could it be worth? But Lionel demurs. He is there strictly to pass judgment on the painting’s authenticity, not – should it prove to be the real thing – to declare its value. Maude will not be denied. Brooks is believable and affecting as Maude wheedles and pleads: We don’t have to talk about this painting, she suggests, but one like it. Offered this hypothetical solution to their stand-off, the great man gives in. An actual Pollock, he allows, might bring a hundred million dollars.

Then comes the presentation, the unveiling, the inspection. The judgment.

Let’s just say the conversation continues. Maude presses a drink of whisky onto her guest. She has a case of the stuff, lifted from the bar on her way out; severance pay, she says.

Here, Lionel’s personality takes a turn. This proper, circumspect, serious-minded man gets a few nips in him and suddenly he begins to leak human frailty. A turn on a dime by a veteran whose scholarly pedigree is a mile long, whose authority is unsurpassed – confessing at this moment, to this person in this place. It’s a handy device, just not very likely. Lionel also commences a rhapsodic, not to say orgasmic, description of Pollock’s way of working, the love the painter made to each recumbent canvas, drizzling his fluids over it as it lay on the floor beneath him. I was taken more by Nussbaum’s reading of, or rather his grappling with, these egregious lines than by their laughable content.

Here, Lionel’s personality takes a turn. This proper, circumspect, serious-minded man gets a few nips in him and suddenly he begins to leak human frailty. A turn on a dime by a veteran whose scholarly pedigree is a mile long, whose authority is unsurpassed – confessing at this moment, to this person in this place. It’s a handy device, just not very likely. Lionel also commences a rhapsodic, not to say orgasmic, description of Pollock’s way of working, the love the painter made to each recumbent canvas, drizzling his fluids over it as it lay on the floor beneath him. I was taken more by Nussbaum’s reading of, or rather his grappling with, these egregious lines than by their laughable content.

As for delivering words that plummet from the lips to the floor, Brooks’ hard-liquor Maude spews f-peppered lines that sound not so much conditioned as forced, imposed. Where does the blame fall for this leaden effect? Shall we fault a tortured text, an actor who’s wearing uncomfortable robes, or a director (Kevin Christopher Fox) who hasn’t corrected the inauthentic impulse or pitch of f-this and f-that, the laundered quality of crude speech that’s supposedly habitual? In any case, all that bad talk comes across as just so much aimless drizzle on a largely empty canvas.

And one last item: When Maude asks Nussbaum’s intellectually convincing art scholar what it is in a genuine work that makes him so certain of it, he invokes the Greek word arete (ah-ray-TAY), which means goodness or virtue, but also as he suggests, truth or authenticity. (Arete is related to aristos, meaning the best, the root word of aristocracy.) A genuine painting or sculpture fairly radiates arete, Lionel says. Whatever qualities Maude’s found canvas may own, he declares after an hour in her crappy trailer, this hard-drinking, desperate, perhaps delusional woman herself possesses…yes, that aforementioned thing. What a guy. I can’t begin to express how deeply I wish he’d kept the thought to himself.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- A look ahead at TimeLine Theatre’s 2016-17 season: Read about it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: Bakersfield Mist, Janet Ulrich Brooks, Mike Nussbaum, Stephen Sachs, TimeLine Theatre