James Levine returns to Ravinia and the CSO, and a tempest gives place to maestro’s Mahler

Review: After absence of 23 years, festival’s former music director leads Chicago Symphony and Chorus in “Resurrection” Symphony.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Even Mother Nature fell silent to listen when conductor James Levine made his much anticipated, storm-framed return to the Ravinia Festival on July 23.

Closing a special circle in his august career, Levine led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a transcendent performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in C minor (“Resurrection”), the very work with which he had made his emergency debut at Ravinia 45 years ago.

Levine, now 73, was little known when at age 27 he was called upon as the desperation choice to stand in for not one but two eminent conductors, Eugene Ormandy and István Kertész, who one after the other had to withdraw from that Mahler Second performance in the summer of 1971.

Six years later, Levine would reprise the Mahler Second Symphony at Ravinia with the CSO. By then he was the festival’s music director. On that night, 19-year-old clarinetist John Bruce Yeh was making his Ravinia debut as a new member of the orchestra. Forty years later, Levine and Yeh were back on stage together, with Mahler. The clarinetist recalls vividly those distant summers with Levine.

Six years later, Levine would reprise the Mahler Second Symphony at Ravinia with the CSO. By then he was the festival’s music director. On that night, 19-year-old clarinetist John Bruce Yeh was making his Ravinia debut as a new member of the orchestra. Forty years later, Levine and Yeh were back on stage together, with Mahler. The clarinetist recalls vividly those distant summers with Levine.

I ran into Yeh, who is now the longest serving clarinetist in the history of the CSO, in mid-July at a chamber music performance at the Tippet Rise Art Center, in southeastern Montana.

“I had auditioned in May 1977 for (former music director Georg) Solti and joined the orchestra for the summer,” Yeh said. “The first work I played was bass clarinet in Mahler 2 with Jimmy. I also did my first recording, ever, with him that same year, of Stravinsky’s ‘Petrouchka,’ for RCA. These were fabulous experiences and when I saw him many years later, in Boston, he brought them up. His memory for those years is amazing. He said he still listens to that ‘Petrouchka’ from time to time.”

“I had auditioned in May 1977 for (former music director Georg) Solti and joined the orchestra for the summer,” Yeh said. “The first work I played was bass clarinet in Mahler 2 with Jimmy. I also did my first recording, ever, with him that same year, of Stravinsky’s ‘Petrouchka,’ for RCA. These were fabulous experiences and when I saw him many years later, in Boston, he brought them up. His memory for those years is amazing. He said he still listens to that ‘Petrouchka’ from time to time.”

Just two months before his sudden appearance at Ravinia, Levine had made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera. Both introductions sparked stunning ascents. Within two years, he was named music director at Ravinia, and in 1976 he was elevated to the same position at the Met. He held the latter post four decades.

When Levine stepped down as Ravinia’s music director in 1993, he said he hoped to return in a guest role as soon as the mounting obligations of his career might permit. No one could have known that next date would be deferred for 23 years.

When Levine stepped down as Ravinia’s music director in 1993, he said he hoped to return in a guest role as soon as the mounting obligations of his career might permit. No one could have known that next date would be deferred for 23 years.

Within a year of his Met and Ravinia debuts, the soaring conductor bowed for the first time with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and that connection also eventually led his being named music director, effective with the 2004-05 season.

A variety of serious health issues led Levine to end his directorship at the Boston Symphony and take the less demanding position of music director emeritus at the end of the Met’s 2015-16 season. He now gets around in a motorized chair, from which he also conducts, and it was in that perambulator that he made his homecoming appearance on an elevated platform at Ravinia. The packed audience in the pavilion stood to deliver a roaring welcome, and Levine beamed, mouthing the words, “Thank you very much.”

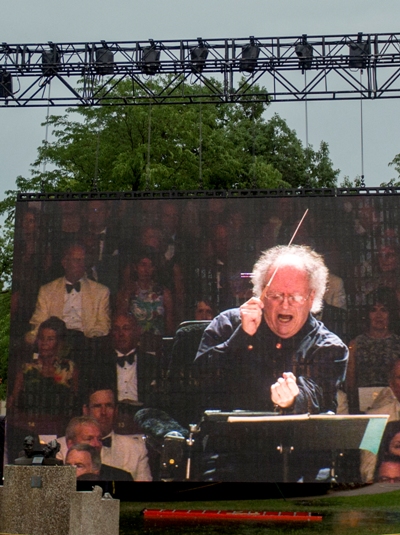

Truth is, he looked vigorous and strong, and showed – in big-screen close-ups during the performance – no sign of the tremors that according to some musicians have blurred his beat and made him increasingly hard to follow. On this night, that right-hand beat was clear and precise, the left hand no less unequivocal in its summoning of expressive emphasis. To the end of Mahler’s epic-length symphony, Levine was completely in control.

Truth is, he looked vigorous and strong, and showed – in big-screen close-ups during the performance – no sign of the tremors that according to some musicians have blurred his beat and made him increasingly hard to follow. On this night, that right-hand beat was clear and precise, the left hand no less unequivocal in its summoning of expressive emphasis. To the end of Mahler’s epic-length symphony, Levine was completely in control.

My guess is he could have conducted with his eyes alone, so thoroughly internalized was this radiant traversal of the Second Symphony. After a dramatically charged opening movement that blended lyrical reflection with sheer ferocity – and after the interval of several minutes that Mahler specifies at the end of that expansive first chapter – Levine took the ensuing slow movement at a pace more suggestive of cosmic time than of earthly measure. It was exquisite. The CSO sustained Levine’s delicate lines without a hint of stress, conjuring music of other spheres.

Mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill’s arresting performance of the “Urlicht,” a song of untrammeled faith that prefaces the finale’s Resurrection, was not only magnetic in its expressive conviction but also vocally glorious. There were only two images that induced me to look at the on-screen displays: the intimate shots of Levine and Cargill. In the second solo role, soprano Ying Fang produced a lovely sound albeit on a rather small scale.

Mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill’s arresting performance of the “Urlicht,” a song of untrammeled faith that prefaces the finale’s Resurrection, was not only magnetic in its expressive conviction but also vocally glorious. There were only two images that induced me to look at the on-screen displays: the intimate shots of Levine and Cargill. In the second solo role, soprano Ying Fang produced a lovely sound albeit on a rather small scale.

The symphony’s grandiose finale brings in the chorus for the first time to sing the hymn “Aufersteh’n” (“Arise, yes, you will rise again, my dust, after a brief rest!”). It mirrors the conclusion of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and Levine’s patient dramatic construction evoked that same transporting effect, a hurtling of the spirit into the empyrean. The CSO Chorus, prepared with characteristic exactitude by Duain Wolfe, managed a thrilling dynamic arc from bare audibility to heaven-storming affirmation.

Happily, all the storming at this performance was on stage. It was more than a little eerie to watch the early evening’s raging tempest, pouring rain and massive lightning, cease utterly right at concert time. Only after the long, long ovation had subsided did the heavens send down their droplets again and flash their distant lights.

It was a veritable obeisance to a great conductor, this scion of Ravinia, James Levine. I could not otherwise explain it.

Related Links:

- CSO’s 2016 season at Ravinia: Program by program details of the 80th anniversary residency

- All highlights of Ravinia’s classical season: Go to Chicago On the Aisle

- Country, rock, indie, R&B, jazz: Read what else Ravinia has in story at Chicago On the Aisle.

Tags: James Levine, John Bruce Yeh, Karen Cargill, Ravinia Festival, Ying Fang