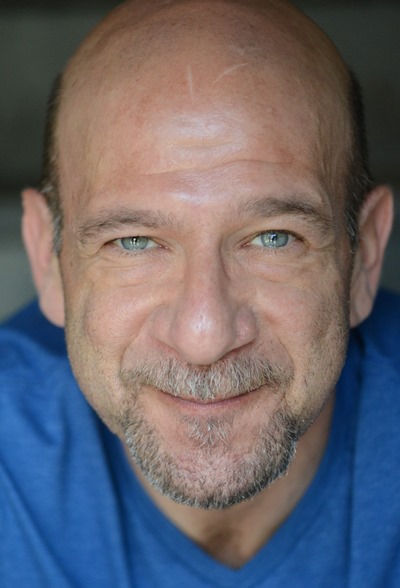

Role Playing: Adam Bitterman, unlikely florist in ‘Seedbed,’ dug deep to create a rare bloom

Interview: For Bryan Delaney’s searing play at Redtwist, actor says he imagined backstory to explain his rough-cut vendor of flowers.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Adam Bitterman’s earthy and lusty and sometimes unnerving performance as the improbable florist Mick, a middle-aged guy enamored of an 18-year-old girl in Bryan Delaney’s “The Seedbed” at Redtwist Theatre, defies you to take your eyes off him. But the veteran actor had his doubts about even taking on the prodigious part, and this elusive character.

“When I read the play, it sort of puzzled me that Mick’s a florist,” says Bitterman. “That didn’t seem like me. But he’s not what you would call a typical florist. The first thing that came to mind was that, regardless of where he is now in life, this clearly was not his first career, and not necessarily his favorite. Yet for one reason or another that we never figure out, he ended up here.”

Here, indeed. Here, if you want to get right down to the dramatic instance, is the home that Mick’s girlfriend Maggie (Abby Dillion) has recently fled – for reasons that are sifted through several filters as the play unfolds. Had Maggie and her step-father Thomas (Mark Pracht) become lovers? Did the girl’s mother Hannah (Jacqueline Grandt) push her out?

Has Mick been played by a pretty girl? Is anyone in this bizarre household capable of telling the truth?

Mick, a Londoner by birth who’s maybe fiftysomething, lives and works in Amsterdam. That’s where, under the most extreme circumstances, he met the Irish lass Maggie. Now she’s brought him home to Ireland to meet the parents – and to announce their impending marriage. Mick tries from hello to show Maggie’s folks that he genuinely loves her. Mom and Dad are not happy, but we soon discover the tangled roots of their discontent run deeper than this dubious news.

In making Mick’s way through this familial thicket, Bitterman got key assists from director Steve Scott and the playwright himself, Bryan Delaney, who was on hand through the rehearsal process and into the first performances.

“It was important to Bryan to differentiate between working-class Mick and this middle-class, even upper-middle-class family,” says Bitterman. “It’s clear to me that Mick has had a rough life, that he has overcome some hurdles. Bryan and I talked about how he probably grew up in rough company. Maybe he had to flee from England.

“Mick has reached a certain level of comfort. He has some money, and he likes to bet on the horses, which can lead you down a path of speculation about his beginnings. He values honesty. He brings up over and over how important that is to him. His relationship with Maggie all boils down to what’s honest. So when he begins to sense he’s being lied to, we see him regress and shed the trappings of civility. Maybe he’s reverting to who he once was.”

By no means, however, were Mick’s complex issues a mere speculative exercise for Bitterman. Mick grapples with his volatile situation in copious dialogue. It’s a huge part, and Bitterman makes no bones about the scale of that challenge.

“I’ve done roles with a lot dialogue before,” he says, “but I don’t think I ever had to learn as much dialogue as this. It’s no exaggeration to say I was terrified. But I also found a lot of support from friends and co-workers from the past. We had a short rehearsal process, and Steve was very generous and understanding. When we were about to go off book, I told him I didn’t know if I was a hundred percent ready. He said just do the best you can. That gave me the freedom to not be worried about it.”

His lines were not Bitterman’s only cause for anxiety. A compact, muscular actor, he was concerned at the start about squaring up with the physically more imposing Mark Pracht as Maggie’s father, in scenes where the two men verge on fighting. But playwright Delaney saw no problem.

“Bryan told me that I look like a boxer, which he considered appropriate for Mick,” the actor recalls. “But what really made it work was the sleeveless T-shirt that (the director) and the costume designer (Cassandra Bowers) came up with in dress rehearsal.”

Near the end of the play, Mick challenges the bigger Thomas. At that moment, in Bitterman’s fiery delivery and coiled posture, we sense a primordial fury that’s just about to explode through the last threads of civilizing restraint. Your money is on Mick.

Still, through it all, this “tame beast” (as Bitterman calls his character) wants desperately to see truth confirmed in Maggie’s protestations of love for him.

“Why is Mick involved with this young girl?” asks Bitterman. “Bryan and I spent a lot of time on that question. I think this older man sees Maggie – he calls her the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen – as his last shot at finding love. That’s why he’s so willing to give her every benefit of doubt.

“During rehearsals, what kept coming back to me was the idea that love doesn’t know age. When you make that connection, everything else seems to fall by the wayside. For Mick, the age difference doesn’t mean as much as the bond he feels. One could question, if the complicating events of the play didn’t happen, would Mick and Maggie last? Is it deep love or a lark? I don’t know the answer.”

Related Links:

- Review of ‘The Seedbed’: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

More Role Playing Interviews:

- Danny McCarthy, pushing broom in ‘The Flick,’ finds vital pulse in long silences

- Mierka Girten, actor with MS, knows wound behind her character’s scars

- Sandra Marquez, as Clytemnestra, sees an exceptional woman in the Greek queen

- Brian Parry says he summoned courage before wit as George in ‘Virginia Woolf’

- Tracy Michelle Arnold debunks madness as force that drives Blanche DuBois

- Christopher Donahue, as Ahab, finds sea’s depth in sadness of a vengeful soul

- Lance Baker embodies ennui, despair of fugitive Jews in ‘Diary of Anne Frank’

- Francis Guinan embraces conflict of father who fled from grim truth in ‘The Herd’

- Sophia Menendian reached back (but not far) as plucky Armenian refugee of 15

- Lindsey Gavel’s distressed Masha, in ‘Three Sisters,’ began with a touch of cheer

- Hollis Resnik felt personal bond with zealous, skeptical scholar in ‘Good Book’

- A.C. Smith is ready undertaker, lord of diner world in ‘Two Trains Running’

- Lia D. Mortensen’s intense portrait of a mentally failing scientist holds mirror to life

- Siobhan Redmond sees re-formed Lady Macbeth as valiant queen in ‘Dunsinane’

- Eileen Niccolai harnessed a storm of emotions to create spark in Williams’ Serafina

- Steve Haggard, aiming at reality, strikes raw core of grieving man in ‘Martyr’

- Shannon Cochran found partners aplenty in sardonic, twice-told ‘Dance of Death’

- Natalie West scaled back comedy to nail laughs, touch hearts in ‘Mud Blue Sky’

- Dave Belden, actor and violinist, adjusted pitch for ‘Charles Ives Take Me Home’

- Joseph Wiens starts at full throttle to convey alienation of ‘Look Back in Anger’

- Shane Kenyon touches charm and hurt of lovable loser in Steep’s ‘If There Is’

- Ramón Camín sees working class values in Arthur Miller’s tragic Eddie Carbone

- Hillary Marren’s charming, rapping witch in ‘Woods’ shapred by hard work, free play

- Mary Beth Fisher embraces both hope, despair of social worker in ‘Luna Gale’

- Brad Armacost switched brothers to do blind, boozy character in ‘The Seafarer’

- Karen Woditsch shapes vowels, flings arms to perfect portrait of Julia Child

- Ora Jones had to find her way into Katherine’s frayed world in ‘Henry VIII’

- Kareem Bandealy tapped roots, hit books for form warlord in ‘Blood and Gifts’

- Eva Barr explored two personas of Alzheimer’s victim to find center of ‘Alice’

- Darrell W. Cox sees theater’s core in closed-off teacher of ‘Burning Boy’

- Chaon Cross turned Court stage into a romper room finding answers in ‘Proof’

- Dion Johnstone turned outsider Antony to bloody purpose in ‘Julius Caesar’

- Noir films gave Justine Turner model for shadowy dame in ‘Dreadful Night’

- Anish Jethmalani plumbs agony of good man battling demons in ‘Bengal Tiger’

- Gary Perez channels his Harlem youth as quiet, unflinching Julio in ‘The Hat’

- Kamal Angelo Bolden sharpened dramatic combinations to play ‘The Opponent’

- In wheelchair, Jacqueline Grandt explores paralysis of neglect in ‘Broken Glass’

- James Ridge thrives in cold skin of Shakespeare’s smiling serpent, Richard III

- Stephen Ouimette brews an Irish tippler with a glassful of illusions in ‘Iceman’

- Ian Barford revels in the wiliness of an ambivalent rebel in Doctorow’s ‘March’

- Chuck Spencer flashes a badge of moral courage in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Price’

- Rebecca Finnegan finds lyrical heart of a lonely woman in ‘A Catered Affair’

- Bill Norris pulled the seedy bum in ‘The Caretaker” from a place within himself

- Diane D’Aquila creates a twice regal portrait as lover and monarch in ‘Elizabeth Rex’

- Dean Evans, in clown costume, enters the darkness of ‘Burning Bluebeard’

- Dan Waller wields a personal brush as uneasy genius of ‘Pitmen Painters’

- City boy Michael Stegall ropes wild cowboy in Raven Theatre’s ‘Bus Stop‘

- Brent Barrett is glad he joined ‘Follies’ as that womanizing, empty cad Ben

- Sadieh Rifai zips among seven characters in one-woman “Amish Project”

- Kirsten Fitzgerald inhabits sorrow, surfs the laughs in ‘Clybourne Park’

- Janet Ulrich Brooks portrays a Russian arms negotiator in ‘A Walk in the Woods’

Tags: Abby Dillion, Adam Bitterman, Bryan Delaney, Cassandra Bowers, Jacqueline Grandt, Mark Pracht, Redtwist Theatre, Steve Scott

No Comment »

2 Pingbacks »

[…] Adam Bitterman, unlikely florist in ‘Seedbed,’ dug deep to create a rare bloom […]