In a Stravinsky night Dutoit and CSO recapture the blaze of ‘Firebird,’ esprit of Symphony in C

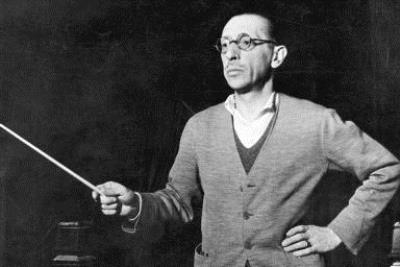

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Charles Dutoit, at Orchestra Hall through May 20.

By Kyle MacMillan

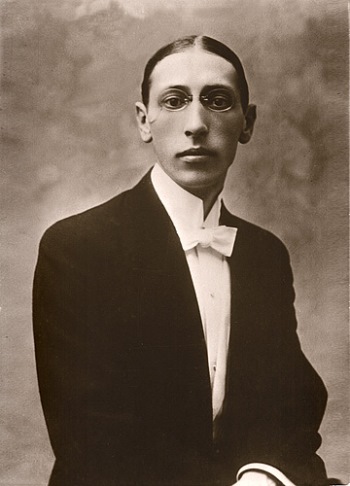

If it is impossible to know what it was like to be at the Paris Opera in 1910 and attend the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s “The Firebird” as part of a glittering production of the Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s vivid, voluptuous version of this now-celebrated masterwork, heard May 19, offered at least a strong suggestion.

Even though certain passages are as familiar as any in classical music, guest conductor Charles Dutoit and the orchestra infused the ballet with vibrancy, immediacy and energy, making it sound fresh — anything but routine. It helped that the orchestra presented the complete version of the ballet (the first time since 2010), not the more frequently heard suite, providing the proper context and build-up for the oft-heard sections.

“The Firebird” was the inevitable culmination of a program focused exclusively on the music of Stravinsky, arguably the most groundbreaking composer of the 20th century. Entire concerts are regularly devoted to Bach or Beethoven, but such offerings can be too much of the same thing. That is not the case, however, with Stravinsky, whose music underwent a series of distinct stylistic phases – two of which were on view here.

“The Firebird” was the inevitable culmination of a program focused exclusively on the music of Stravinsky, arguably the most groundbreaking composer of the 20th century. Entire concerts are regularly devoted to Bach or Beethoven, but such offerings can be too much of the same thing. That is not the case, however, with Stravinsky, whose music underwent a series of distinct stylistic phases – two of which were on view here.

Dutoit, who remains best known for his tenure as music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra from 1977 through 2002, is a regular guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony and was back with the orchestra for two sets of concerts. Last week’s program was devoted to French and Spanish works, two of the maestro’s mainstays, and this concert featured another aspect of the repertoire for which he is well known. Among his more than 200 recordings are albums devoted to the two main works on this program – “The Firebird” and the Symphony in C.

This all-Stravinsky program opened with “Fireworks,” an early work that certainly set off some fireworks in the music world when it debuted in 1909, announcing a composer of breathtaking promise. Although this piece comes four years before Stravinsky’s revolutionary ballet, “The Rite of Spring,” many of the seeds of that radical work can be heard here, especially Stravinsky’s innovative use of an expanded orchestra with an extensive percussion section and the amount of sheer musical ambition packed into less than five minutes.

Dutoit and the orchestra plunged into it, presenting an appealingly kinetic interpretation that packed a punch and captured the slightly strange, off-balance quality of this forward-looking music with its clipped, colliding and overlapping motifs.

Historical connections ran all through this concert, starting with the fact that “Fireworks” was the first Stravinsky work that the Chicago Symphony performed, in 1915. Of greater importance to musical history, it also happens to be the composer’s first composition heard by Diaghilev, the great impresario who was a key catalyst in the development of the early 20th-century avant-garde. Immediately recognizing Stravinsky’s promise, he hired the budding composer to do some arrangements and commissioned him to write what became “The Firebird,” a ballet that would be choreographed by the now-legendary Michel Fokine and become an instant classic.

But before proceeding to the “Firebird,” Thursday’s program actually jumped ahead in time to one of Stravinsky’s masterworks from his neo-classical period – the Symphony in C. The composer had scores by Haydn and Beethoven at his side as he wrote this piece in 1938-40, and it manages to both reflect the spirit of those two composers but also sound modern at the same time with its unconventional, slightly dissonant harmonies and intriguing orchestral colors and rhythmic complexities.

But before proceeding to the “Firebird,” Thursday’s program actually jumped ahead in time to one of Stravinsky’s masterworks from his neo-classical period – the Symphony in C. The composer had scores by Haydn and Beethoven at his side as he wrote this piece in 1938-40, and it manages to both reflect the spirit of those two composers but also sound modern at the same time with its unconventional, slightly dissonant harmonies and intriguing orchestral colors and rhythmic complexities.

Stravinsky wrote it during a tumultuous time, when the death of three family members and the onset of World War II forced him to leave Europe. He accepted a lecture invitation from Harvard University and moved to the United States, eventually settling in Los Angeles where he finished this symphony.

These considerable travails, though, are not reflected in the music, which maintains a largely upbeat, untroubled countenance. “I did not seek to overcome my grief by portraying or giving expression to it in music,” Stravinsky wrote, “and you will listen in vain, I think, for traces of this sort of personal emotion.”

Although the symphony is scored for a full orchestra, it has a smaller-scale, chamber orchestra feel that Dutoit played up, bringing a lightness to the work throughout and a well-suited intimacy and calm to the quieter, more open second movement. At the same time, the conductor subtly balanced and focused the cross-currents of old and new, behaved and brash, which run through this work.

Dutoit and orchestra brought a buoyant, rhythmic thrust and ebullience to the Beethoven-tinged first movement, a feeling that returned with the orchestra’s snappy take on the scherzo third movement. The fourth movement begins with a slow, somber mix of trombones, French horns and bassoons, then speeds up and develops into a satisfying resolution.

This presentation of the Symphony in C was part of orchestra’s season-long celebration of its 125th anniversary in which it is revisiting works that were given their world or American premieres by the Chicago Symphony. Stravinsky himself was on the podium in Orchestra Hall for the world premiere of this work in November 1940, and the critics in attendance immediately realized the significance of the new creation they were hearing. That premiere clearly stands as one of the most important in the Chicago Symphony’s history, giving this performance an added level of resonance.

“The Firebird,” the evening’s much-anticipated focal point, came on the second half, and Dutoit and the CSO delivered the goods – a huge, all-encompassing performance that completely captured the intoxicating exoticism and rich evocativeness of Stravinsky’s extraordinary score. This nearly 50-minute work is all about painting sound pictures, and if even one had never seen a dance version of the ballet, it was easy to imagine the story playing out in one’s mind.

“The Firebird,” the evening’s much-anticipated focal point, came on the second half, and Dutoit and the CSO delivered the goods – a huge, all-encompassing performance that completely captured the intoxicating exoticism and rich evocativeness of Stravinsky’s extraordinary score. This nearly 50-minute work is all about painting sound pictures, and if even one had never seen a dance version of the ballet, it was easy to imagine the story playing out in one’s mind.

This work calls for a much-expanded orchestra, which here included three harps, four flutists and piccolo players, two contrabassoonists and five percussionists, not to mention piano and celeste. Dutoit drew forth involved, committed performances — big, sweeping ensemble playing and many solos. Acting principal French horn Daniel Gingrich was unflappable in solos that were alternately plaintive, searching and celebratory. Other standouts included assistant principal oboe Michael Henoch, who also shone in the Symphony in C, and principal bassoon Keith Buncke.

Related Links:

- Pianist Lang Lang plays Prokofiev with the CSO and Dutoit one night only May 21: Details at CSO.org

- Preview of the Chicago Symphony’s complete 2015-15 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: Ballets Russes, Charles Dutoit, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Sergei Diaghilev