‘Satchmo at the Waldorf’: As Louis Armstrong nears end, he recalls a winding path to fame

Review: “Satchmo at the Waldorf” by Terry Teachout, at Court Theatre extended through Feb. 14. ★★★

Review: “Satchmo at the Waldorf” by Terry Teachout, at Court Theatre extended through Feb. 14. ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Terry Teachout’s “Satchmo at the Waldorf,” a one-man bio-drama on the life of jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong, is an affecting, often surprising and raspingly funny alchemy of brass and clay.

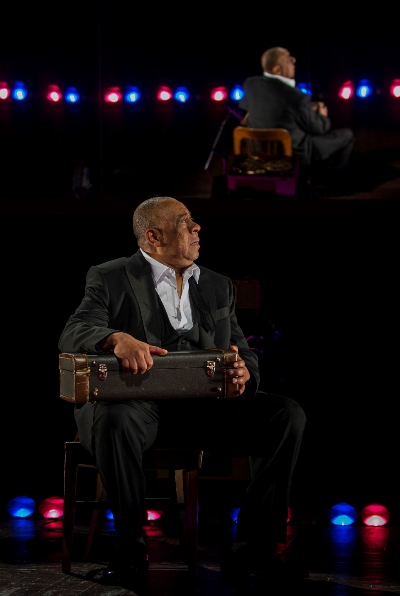

A free-wheeling riff on Teachout’s own 2009 biography titled “Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong,” this 2011 monodrama – actually one actor, Barry Shabaka Henley switching among several characters — is set backstage at the conclusion of the great trumpeter’s final performance a few months before his death in 1971.

A free-wheeling riff on Teachout’s own 2009 biography titled “Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong,” this 2011 monodrama – actually one actor, Barry Shabaka Henley switching among several characters — is set backstage at the conclusion of the great trumpeter’s final performance a few months before his death in 1971.

The accuracy of some details in Teachout’s stage play has been disputed, but the scholarly author, a jazz expert, has waved off those criticisms with the simple reply that “Satchmo at the Waldorf” is a work of fiction based on a real life. Indeed, it is a lively, engaging fiction but also a credible portrait with a human heart.

Brass and clay. The trumpet virtuoso and the man. In the recollection of a man whose body is breaking down, we wander, bounce, careen back through the phenomenal journey that brought a talented young black kid from a New Orleans reform school to the world’s stages and the height of fame. Ultimately, musical genius prevailed over prejudice and Armstrong achieved the once-unthinkable, commanding a room at the Waldorf — not just to perform in, but to sleep in.

Henley is a roundly appealing Louis Armstrong, both the familiar one all smiling warmth and irresistible charm and the one we didn’t know: weary, disaffected, accusatory, spewing f-words like a sailor in rough seas. The orneriness mostly springs from the trumpeter’s longtime relationship with the only manager he ever had, Joe Glaser, a Chicago tough guy – also portrayed by Henley — from the Capone crowd who took the young Armstrong under his wing in a moment of crisis and guided him down a glittering pathway to success.

In a way, their relationship resembled that of Elvis Presley and Colonel Tom Parker. Both performers essentially handed their lives over to their minders and did what they were told, and what they were told had a lot more to do with making everyone rich than with making art. One of Glaser’s first edicts involves Armstrong’s trumpet: Give it a rest, Louis. Nobody wants to hear all those high notes. You’ve got a great voice. Sing. That’s what the people want.

In a way, their relationship resembled that of Elvis Presley and Colonel Tom Parker. Both performers essentially handed their lives over to their minders and did what they were told, and what they were told had a lot more to do with making everyone rich than with making art. One of Glaser’s first edicts involves Armstrong’s trumpet: Give it a rest, Louis. Nobody wants to hear all those high notes. You’ve got a great voice. Sing. That’s what the people want.

So Armstrong sings, and smiles. He’s genuinely happy. He’s also still amazed at some of the odd turns in his life. He recalls recording “Hello, Dolly” at Glaser’s insistence. A few weeks after cutting the disc, when he’s touring with the band, the audience begins clamoring for “Hello, Dolly,” which Armstrong and the boys have so completely forgotten about that they can’t even put together an arrangement – until a copy of the record is sent to them as a refresher. “Hello, Dolly” is a crappy song, says Armstrong, but the public never got tired of it.

Yet Armstrong’s celebrity comes at the cost of some stinging criticism from his more progressive jazz peers, black men, notably fellow trumpeter Miles Davis, 25 years younger and openly disdainful of what he perceives as sucking up to white folks. The conflict is serious, but Henley’s super-cool impersonation of Davis – the dark glasses, the measured whispering speech, the dripping condescension – is riotously funny.

Henley migrates niftily, instantly among the personas of Armstrong in that “sawmill” voice and Glaser in a vulgarity-laced aura of practicality and (happily, more than once) the smoothly aloof Davis. It’s clever and entertaining.

What’s missing, or merely hinted at, is the music itself. Henley picks up, caresses, puts away the trumpet and declares it to be his second self (Glaser’s objections notwithstanding). But this stage work assumes that we know – depends on our knowing — just how great a trumpet player Armstrong really was. A smattering of recorded music in the background scarcely makes that connection. The argument might be made that “Satchmo” is about the man, but one could say the man and his music are the same thing. Allowing substantive interjections of full-blown recorded sound could only underline the quality of genius in view here.

What’s missing, or merely hinted at, is the music itself. Henley picks up, caresses, puts away the trumpet and declares it to be his second self (Glaser’s objections notwithstanding). But this stage work assumes that we know – depends on our knowing — just how great a trumpet player Armstrong really was. A smattering of recorded music in the background scarcely makes that connection. The argument might be made that “Satchmo” is about the man, but one could say the man and his music are the same thing. Allowing substantive interjections of full-blown recorded sound could only underline the quality of genius in view here.

Teachout’s one-act play runs about 90 minutes. Around 70 minutes in, this production directed by Charles Newell lost steam on opening night, which came after several preview performances. The narrative tension fell slack, in part because Henley persistently dropped lines. The demands on the solitary actor are formidable, but the bobbles and recoveries eventually got in the way.

Set designer John Culbert’s simple stage layout is brilliantly enhanced by the metaphor of an expansive mirror at the rear; and Keith Parham’s lighting, by turns subtle and emotionally charged, modulates with the narrative — almost like music.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Preview of Court Theatre’s complete 2015-16 season: Read it at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

Tags: Barry Shabaka Henley, Charles Newell, Court Theatre, John Culbert, Keith Parham, Louis Armstrong, Satchmo at the Waldorf, Terry Teachout