Role Playing: Christopher Donahue, as Ahab, finds sea’s depth in sadness of a vengeful soul

Interview: Melville’s stormy character evokes Shakespeare, but more in madness than tragedy, says the star of “Moby Dick” at Lookingglass Theatre. The production runs through Aug. 28.

Interview: Melville’s stormy character evokes Shakespeare, but more in madness than tragedy, says the star of “Moby Dick” at Lookingglass Theatre. The production runs through Aug. 28.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Christopher Donahue contemplates the weathered, craggy, doggedly vengeful figure of Captain Ahab, the iconic central character of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick,” whose cosmic persona Donahue brings into vivid focus on the stage at Lookingglass Theatre. And in the driven whale hunter, the actor finds a paradox.

“He is quite Shakespearean – he is Macbeth and King Lear,” says Donahue. “But I hesitate to call him a tragic figure. He’s so crazy and evil, and incredibly sad at the same time. Ahab abides far away from humanity. He is as much a creature of the sea as the creature he’s trying to kill. The sea lives in him. I think he believes himself to be as strong and tumultuous as the sea itself.”

Ahab knows the fierce and defiant whale Moby Dick from a painful previous encounter when the great beast took his leg. Melville’s story is one of epic payback, of one man resolved to subdued an elemental force of nature, whatever the cost to his ship’s crew, whatever the danger to himself. He will pursue this demonic leviathan to the ends of the earth and for a long as it takes.

Ahab knows the fierce and defiant whale Moby Dick from a painful previous encounter when the great beast took his leg. Melville’s story is one of epic payback, of one man resolved to subdued an elemental force of nature, whatever the cost to his ship’s crew, whatever the danger to himself. He will pursue this demonic leviathan to the ends of the earth and for a long as it takes.

“Melville describes Ahab as ‘a grand ungodly god-like man,’” says Donahue. “I don’t know exactly what that might mean, but I’m sure Ahab thinks of himself that way, as godly. I see him as Melville sees him, I suppose. I’m a huge fan of the book. It’s primary to me. I’ve read it four times in my life. It’s really about seeing yourself in the other. For Ahab, the whale must be a projection of something about himself.

“His madness increases with everything that goes wrong along with way, and he’s never daunted. These are the cards dealt to him and he’s going to play them. He’s aware of his own madness – a wild madness that’s calm only to comprehend itself. ‘What is this thing that drives me?’ It’s as big a mystery as the whale itself, and he’s determined to find its meaning and dominate it.”

That said, it is hardly a heroic figure who first presents himself to us in this stage adaptation by Lookingglass ensemble member David Catlin, who also directs the production. Though Ahab has been talked about in grandiose, albeit mysterious, terms before we meet him, upon his entrance – through an illuminated doorway off to one side of the set – he cuts an unprepossessing figure; indeed, he seems quite ordinary. Is this the soul that launched so fierce a quest?

That said, it is hardly a heroic figure who first presents himself to us in this stage adaptation by Lookingglass ensemble member David Catlin, who also directs the production. Though Ahab has been talked about in grandiose, albeit mysterious, terms before we meet him, upon his entrance – through an illuminated doorway off to one side of the set – he cuts an unprepossessing figure; indeed, he seems quite ordinary. Is this the soul that launched so fierce a quest?

“It’s an odd feeling to be revealed in that way,” Donahue admits. “The first time we worked on it, I sort of wandered out, not quite sure of how this was going to work. In the book Ahab is very present on deck for a long time without speaking, staring grimly out to sea. He’s an ordinary guy with something serious on his mind.

“But that particular doorway and that light – it’s death’s door. He appears out of the specter of death, this shadowy figure emerging out of light. That was very deliberate on (director) Catlin’s part. There is great resonance here in terms of how Ahab regards the sun – the great giver of life that doesn’t renew life. We see this later when a whale, dying on the ship’s deck, gazes toward the sun as if seeking renewal, but finds none. And Ahab is no more daunted by the sun than the sea. He says, ‘I’d strike at the very sun if it so offended me’ as Moby Dick does.”

Yet Donahue also sees in Ahab’s unwavering gaze a spark of humanity. If he is prepared to expend his crew in this quest for Moby Dick, there is at least one in their number whom Ahab regards with respect, even a certain tenderness: his first mate, Starbuck (played by Kareem Bandealy).

Yet Donahue also sees in Ahab’s unwavering gaze a spark of humanity. If he is prepared to expend his crew in this quest for Moby Dick, there is at least one in their number whom Ahab regards with respect, even a certain tenderness: his first mate, Starbuck (played by Kareem Bandealy).

“The only one who moves Ahab is Starbuck, who perhaps reminds him of his own son. There are moments when his humanity almost takes over. But Ahab will not allow that. The crew has been carefully chosen – men who can be easily convinced. And he makes his hard sell immediately, with the offer of a gold coin to the one who spots Moby Dick and the pledge of ritual liquor.”

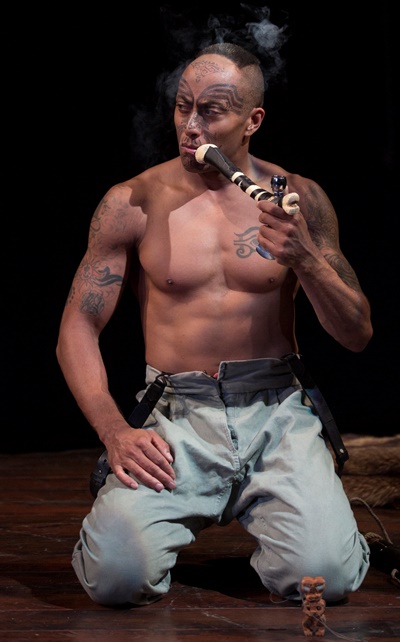

Running in parallel to the fused mysteries of Ahab and Moby Dick is the opposite imponderable of Queequeg, an imposing harpooner and son of a Pacific island king. A great bond forms between this black man of few words and clear moral principles and Ishmael, sole survivor of Ahab’s ill-fated venture and thus narrator of the tale. Donahue sees Queequeg as the psychological bookend to Ahab.

“While the whale is blank (indeed white, like paper not yet written upon), Queequeg’s full life is written (in hieroglyphs) on his body. Queequeg and Ishmael find a deep connection in their differences, which I think is an essential point of the book. Ahab never makes such a positive connection. The very thing he is trying to kill is the thing he most closely identifies with.

“I love the way Anthony (Fleming III) plays Queequeg. He’s charming, tantalizing and funny – a great counterpoint to the complete rejection of humanity that Ahab represents, and a big part of why this show is successful.”

“I love the way Anthony (Fleming III) plays Queequeg. He’s charming, tantalizing and funny – a great counterpoint to the complete rejection of humanity that Ahab represents, and a big part of why this show is successful.”

Another key to adaptor-director Catlin’s convincing stagecraft, says Donahue, is the sheer physicality of a production steeped in elegant acrobatics. The show is a co-production between Lookingglass and the Actors Gymnasium.

“Catlin threw us all into the water together, and we happily went,” says the actor. “We spent a lot of time putting together the physical movement and acrobatics and choreography – the spectacle. If it was all talking – or in my case, yelling – it would be 15 hours long and not very interesting. Catlin has translated things into beautiful visuals that express a human vocabulary.

“You watch people move through space in ingenious ways that take your breath away. It is monumental, and it makes your jaw go slack. It’s a great sadness to me that I don’t get to go on one of those awesome (suspended) whaling boats.”

Donahue also singled out the three Fates (played by Monica West, Kasey Foster and Emma Cadd) as vital to both the story’s idiom and its edge. As an observing Greek-like chorus or singing a chantey or portraying townsfolk, the three women blow through the production like shifting winds. Their final guise, as the great whale itself, is stunning.

Donahue also singled out the three Fates (played by Monica West, Kasey Foster and Emma Cadd) as vital to both the story’s idiom and its edge. As an observing Greek-like chorus or singing a chantey or portraying townsfolk, the three women blow through the production like shifting winds. Their final guise, as the great whale itself, is stunning.

“They’re one of the best things about the show,” says Donahue. “They’re absolutely horrifying as Moby Dick. I don’t know if the audience can even understand. I have the pleasure of being right up next to them in that last scene, and I can tell you it’s hard to believe they’re actually the same three women. I’m very compelled by them – at every performance.”

Related Links:

- Review of ‘Moby Dick’ at Lookingglass: Read in at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

More Role Playing Interviews:

- Lance Baker embodies ennui, despair of fugitive Jews in ‘Diary of Anne Frank’

- Francis Guinan embraces conflict of father who fled from grim truth in ‘The Herd’

- Sophia Menendian reached back (but not far) as plucky Armenian refugee of 15

- Lindsey Gavel’s distressed Masha, in ‘Three Sisters,’ began with a touch of cheer

- Hollis Resnik felt personal bond with zealous, skeptical scholar in ‘Good Book’

- A.C. Smith is ready undertaker, lord of diner world in ‘Two Trains Running’

- Lia D. Mortensen’s intense portrait of a mentally failing scientist holds mirror to life

- Siobhan Redmond sees re-formed Lady Macbeth as valiant queen in ‘Dunsinane’

- Eileen Niccolai harnessed a storm of emotions to create spark in Williams’ Serafina

- Steve Haggard, aiming at reality, strikes raw core of grieving man in ‘Martyr’

- Shannon Cochran found partners aplenty in sardonic, twice-told ‘Dance of Death’

- Natalie West scaled back comedy to nail laughs, touch hearts in ‘Mud Blue Sky’

- Dave Belden, actor and violinist, adjusted pitch for ‘Charles Ives Take Me Home’

- Joseph Wiens starts at full throttle to convey alienation of ‘Look Back in Anger’

- Shane Kenyon touches charm and hurt of lovable loser in Steep’s ‘If There Is’

- Ramón Camín sees working class values in Arthur Miller’s tragic Eddie Carbone

- Hillary Marren’s charming, rapping witch in ‘Woods’ shapred by hard work, free play

- Mary Beth Fisher embraces both hope, despair of social worker in ‘Luna Gale’

- Brad Armacost switched brothers to do blind, boozy character in ‘The Seafarer’

- Karen Woditsch shapes vowels, flings arms to perfect portrait of Julia Child

- Ora Jones had to find her way into Katherine’s frayed world in ‘Henry VIII’

- Kareem Bandealy tapped roots, hit books for form warlord in ‘Blood and Gifts’

- Eva Barr explored two personas of Alzheimer’s victim to find center of ‘Alice’

- Darrell W. Cox sees theater’s core in closed-off teacher of ‘Burning Boy’

- Chaon Cross turned Court stage into a romper room finding answers in ‘Proof’

- Dion Johnstone turned outsider Antony to bloody purpose in ‘Julius Caesar’

- Noir films gave Justine Turner model for shadowy dame in ‘Dreadful Night’

- Anish Jethmalani plumbs agony of good man battling demons in ‘Bengal Tiger’

- Gary Perez channels his Harlem youth as quiet, unflinching Julio in ‘The Hat’

- Kamal Angelo Bolden sharpened dramatic combinations to play ‘The Opponent’

- In wheelchair, Jacqueline Grandt explores paralysis of neglect in ‘Broken Glass’

- James Ridge thrives in cold skin of Shakespeare’s smiling serpent, Richard III

- Stephen Ouimette brews an Irish tippler with a glassful of illusions in ‘Iceman’

- Ian Barford revels in the wiliness of an ambivalent rebel in Doctorow’s ‘March’

- Chuck Spencer flashes a badge of moral courage in Arthur Miller’s ‘The Price’

- Rebecca Finnegan finds lyrical heart of a lonely woman in ‘A Catered Affair’

- Bill Norris pulled the seedy bum in ‘The Caretaker” from a place within himself

- Diane D’Aquila creates a twice regal portrait as lover and monarch in ‘Elizabeth Rex’

- Dean Evans, in clown costume, enters the darkness of ‘Burning Bluebeard’

- Dan Waller wields a personal brush as uneasy genius of ‘Pitmen Painters’

- City boy Michael Stegall ropes wild cowboy in Raven Theatre’s ‘Bus Stop‘

- Brent Barrett is glad he joined ‘Follies’ as that womanizing, empty cad Ben

- Sadieh Rifai zips among seven characters in one-woman “Amish Project”

- Kirsten Fitzgerald inhabits sorrow, surfs the laughs in ‘Clybourne Park’

- Janet Ulrich Brooks portrays a Russian arms negotiator in ‘A Walk in the Woods’

Tags: David Catlin, Herman Melville, Kareem Bandealy, Lookingglass Theatre, Moby Dick

1 Pingbacks »