‘Moby Dick’ at Lookingglass: A man’s obsessive drive to annihilate a whale surges to electric life

“Moby Dick,” adapted by David Catlin from the novel by Herman Melville, at Lookingglasss Theatre through Aug. 28. ★★★★★

“Moby Dick,” adapted by David Catlin from the novel by Herman Melville, at Lookingglasss Theatre through Aug. 28. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Translating a great novel into a successful stage work is hardly a mere matter of reformulation. They are different beasts, novel and play: It isn’t enough to make the one familiar again as the other, iconic characters now costumed before us flitting in and out of scenes together, speaking lines that resonate deeply in our collective consciousness. It is rare to find a novel fine-tuned to the idiom of drama.

All the more marvelous, then, is David Catlin’s imaginative, poetic, indeed galvanic adaptation of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” for Lookingglass Theatre.

Catlin, a member of the Lookingglass ensemble, also directs this world premiere venture – or rather I should say adventure, this metaphorical plunge into the darkness of human obsession: the hot, almost holy pursuit of a great and fearsome whale by a man who has lost all other purpose in life, who readily and indifferently expends the lives of those around him in his vengeful, headlong quest to find and kill Moby Dick.

Catlin, a member of the Lookingglass ensemble, also directs this world premiere venture – or rather I should say adventure, this metaphorical plunge into the darkness of human obsession: the hot, almost holy pursuit of a great and fearsome whale by a man who has lost all other purpose in life, who readily and indifferently expends the lives of those around him in his vengeful, headlong quest to find and kill Moby Dick.

No more than Melville’s novel is Catlin’s kinetic adaptation simple entertainment. It is wonderful story-telling fraught with moral conflict, human foible, mythic mystery and the insuperable power of nature, the illimitable ocean, the god-like quarry. It is will against sinister, unbreakable will. And the whole of it crashes home with overwhelming force on the Lookingglass stage.

“Moby Dick” is rife with symbolism, metaphor interwoven with metaphor, good opposite evil, the rational colliding with the irrational, the sacred and the profane cast upon the same wide water. And essentially, the sum of it all resides in the solitary figure of Captain Ahab, a whaler for two score years who has lost a leg to the dread leviathan called Moby Dick, and who will have vengeance.

Christopher Donahue is a beguiling Captain Ahab, the very disembodiment of a man who has transcended the cares and consciousness of the flesh in his spiritual quest. He maintains only the most tenuous connection to rational thought and the impediments of necessity. He agrees, after the first long weeks at sea, to let his crew lower their whaling boats and let off steam in a hunt. In a crisis, Ahab reluctantly allows his first mate Starbuck (the warmly personable Kareem Bandealy) to empty the ship’s hold to find the source of a whale oil leak – but only after threatening to shoot the insistent officer.

Christopher Donahue is a beguiling Captain Ahab, the very disembodiment of a man who has transcended the cares and consciousness of the flesh in his spiritual quest. He maintains only the most tenuous connection to rational thought and the impediments of necessity. He agrees, after the first long weeks at sea, to let his crew lower their whaling boats and let off steam in a hunt. In a crisis, Ahab reluctantly allows his first mate Starbuck (the warmly personable Kareem Bandealy) to empty the ship’s hold to find the source of a whale oil leak – but only after threatening to shoot the insistent officer.

The spirit, and sometimes the specific letter, of Shakespeare permeates “Moby Dick” and specifically the character of Ahab. In Donahue’s ranting, brooding, oblivious Captain we see a melding of that remorseless schemer Richard III and the unmoored Lear. Then there’s the “Hamlet” moment when desperate, disillusioned Starbuck has his pistol cocked and pointed at Ahab’s back (is this Claudius praying?), but pauses to contemplate the law and decides on the righteous course.

But the longest Shakespearean shadow falls when a crew member, rescued from near drowning, tells the captain he heard a voice in the depths tell him that hemp alone could kill Ahab. This rather direct draw on the weird sisters’ sly assurances to the Scottish king in “Macbeth” only bolsters the captain’s confidence: Hemp obviously refers to the gallows and he is safe aboard the Pequod. Or perhaps not.

But the longest Shakespearean shadow falls when a crew member, rescued from near drowning, tells the captain he heard a voice in the depths tell him that hemp alone could kill Ahab. This rather direct draw on the weird sisters’ sly assurances to the Scottish king in “Macbeth” only bolsters the captain’s confidence: Hemp obviously refers to the gallows and he is safe aboard the Pequod. Or perhaps not.

In the much larger picture one can only revel in the beauty of Melville’s language, which is absolutely worthy of Shakespeare. Catlin’s adaptation preserves great stretches of it in glorious monologues – on life and the part of it that’s already sacrificed, on this grail-like quest — that Donahue delivers to breathtaking effect.

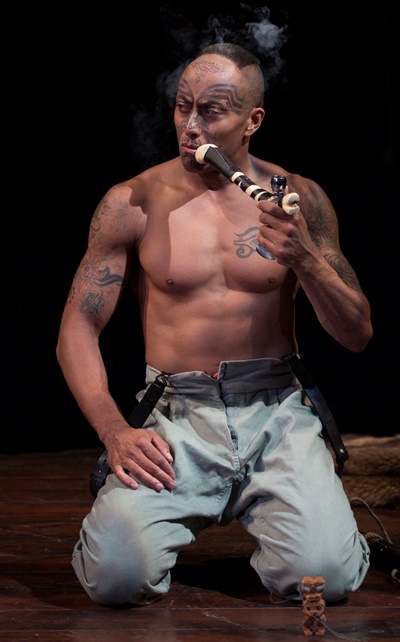

Opposite Donahue’s dubiously visionary Ahab is the equally fetching performance by Anthony Fleming III as the quite clear-sighted Queequeg – tall, muscular, fearsome harpooner, scion of a Pacific island king, gentle man with a functioning moral compass. Physically, Fleming cuts a stunning figure, but he’s also a savvy actor who commands the stage whenever he is in view, certainly whenever he speaks.

Which brings me to the story-teller. Call him Ishmael, sole survivor of Ahab’s folly, a rookie whaler who comes immediately under Queequeg’s wing in a very funny episode that involves sleeping arrangements and a smoking pipe that doubles as a tomahawk. Jamie Abelson is an amiable Ishmael, a faithful observer who generally seems as amazed as the rest of us.

This show is a co-production with the Actors Gymnasium, but while there’s an important physical component, it is the furthest thing from circus spectacle. The modest factor of acrobatics lies purposefully within the narrative and really looks more like aerial ballet – though more often representing underwater action, and convincingly so.

This show is a co-production with the Actors Gymnasium, but while there’s an important physical component, it is the furthest thing from circus spectacle. The modest factor of acrobatics lies purposefully within the narrative and really looks more like aerial ballet – though more often representing underwater action, and convincingly so.

Catlin also makes creative use of three female figures (or Fates – Emma Cadd, Kasey Foster, Monica West) who serve in various capacities, usually as a trio: chorus-like resonators of events and emotions, singers of chanteys, personification of the deep black sea, even the indomitable whale itself.

Courtney O’Neill’s vivid set design, which frames the entire house within the rib cage of something very large, provides whaling boats that rise overhead so that we assume a submarine perspective on the watery ballet-acrobatics.

Expressive costumes (Carolyn Sullivan), evocative lighting (William C. Kirkham) and richly textured sound (Rick Sims) all make essential contributions to this indelible night of theater.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Anthony Fleming III, Carolyn Sullivan, Christopher Donahue, Courtney O'Neill, David Catlin, Emma Cadd, Herman Melville, Jamie Abelson, Kareem Bandealy, Kasey Foster, Lookingglass Theatre, Moby Dick, Monica West, Rick Sims, William C. Kirkham