At heart of Beethoven’s grandiose ‘Emperor,’ pianist Paul Lewis detects an image of grace

Preview: British virtuoso, who will play with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Jan. 8-10, says there’s more than flamboyance to the Fifth Piano Concerto.

Preview: British virtuoso, who will play with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Jan. 8-10, says there’s more than flamboyance to the Fifth Piano Concerto.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

At the core of Beethoven’s “Emperor” Piano Concerto, says British virtuoso Paul Lewis, dwells a tenderness that belies the work’s outwardly heroic trappings. That lyrical middle chapter, he says, bespeaks the concerto’s true heart.

“Liszt called the slow movement of the ‘Emperor’ an angel between two demons,” says Lewis, who plays Beethoven’s last and most exuberant piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Vasily Petrenko in performances Jan. 8-10 at Orchestra Hall. “Perhaps that should be amended to an angel between two heroes.”

“Liszt called the slow movement of the ‘Emperor’ an angel between two demons,” says Lewis, who plays Beethoven’s last and most exuberant piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Vasily Petrenko in performances Jan. 8-10 at Orchestra Hall. “Perhaps that should be amended to an angel between two heroes.”

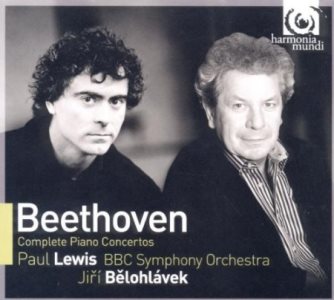

Lewis, 42, speaks from many voyages through the rigorous, challenging and indeed elusive world of Beethoven’s piano music. Besides playing the five concertos as well as the 32 sonatas all over the world, he has recorded that whole body of work in both genres, the concertos with conductor Jiří Bělohlávek and the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Harmonia Mundi).

“It’s important to play a wide range of a composer because the wider your experience, the more you are informed,” Lewis says, speaking by phone from his London residence. “I see Beethoven’s sonatas and concertos in much the same light. They have a common denominator, the same foundation in the sense that Beethoven always speaks about common things. In Beethoven as in Schubert, what you’re trying to get across is something so innately human that we can all understand.

“It’s important to play a wide range of a composer because the wider your experience, the more you are informed,” Lewis says, speaking by phone from his London residence. “I see Beethoven’s sonatas and concertos in much the same light. They have a common denominator, the same foundation in the sense that Beethoven always speaks about common things. In Beethoven as in Schubert, what you’re trying to get across is something so innately human that we can all understand.

“It’s about our lives, but it’s not about answers. There is no answer. The message of the music reflects the experiences of our lives. It’s a journey, but it isn’t about arriving anywhere. You’re simply at another point on that journey – at a different place every time you look.”

If the “Emperor” is a hero’s journey, it’s not altogether Siegfried swashbuckling his way down the Rhine. There’s a generous factor of bravura, to be sure. But Lewis cautions against reducing the work to a visceral contest between piano and orchestra.

“Certainly, the Fifth Piano Concerto can feel obstreperous, and that quality is often underlined in performance,” he says. “If that were all it were about, it wouldn’t add up to great music. The truth is that despite its big, epic character, the ‘Emperor’ is really quite elusive. You’re the heroic soloist one second, only to disappear within a framework of chamber music the next. If you try to present all sides of the concerto in balance, you get the most accurate view.”

For all its mercurial emotion, the “Emperor,” says Lewis, has not produced the extreme highs and lows on the concert stage that he has known in performances of the more contained – some might say more elegant — Fourth Piano Concerto.

“The Fourth feels fragile in so many ways, where the Fifth is more robust, bigger boned,” says the pianist. “Compared with the Fourth Concerto, the Fifth can withstand a little more (abuse). I’ve had some of my happiest concert experiences with the Fourth, and some of my worst. I’ve never hit those lower extremes with the ‘Emperor.’”

“The Fourth feels fragile in so many ways, where the Fifth is more robust, bigger boned,” says the pianist. “Compared with the Fourth Concerto, the Fifth can withstand a little more (abuse). I’ve had some of my happiest concert experiences with the Fourth, and some of my worst. I’ve never hit those lower extremes with the ‘Emperor.’”

Lewis, who found his own way into the piano before he received his first lessons at age 12, says he learned the difference between technical wizardry a true musicianship from pianist Alfred Brendel, with whom he studied periodically through the decade of the 1990s.

Yet, with a sigh, he acknowledges that specific benefits of his work with Brendel, one of the most formidable pianists of the last century, would be hard to pin down.

“It’s a question I still struggle to answer,” he says. “It was a profound experience to see at close range someone who was a great pianist, but more than that, a musician first. That is to say, Brendel was a great musician who happened to play the piano. Purely pianistic issues were of no interest to him.

“But to be able to see first-hand how he achieved what he did – matters of articulation, his masterly use of the sustaining pedal, everything that had to do with color – was quite inspiring. Yet if you tried to copy what he did, it was a disaster, so strong was his own musical personality. You had to translate all that into your own language. I learned not to take anything to him that I was about to play. He would attempt to impart so much information that I didn’t even know what the notes were any more.”

“But to be able to see first-hand how he achieved what he did – matters of articulation, his masterly use of the sustaining pedal, everything that had to do with color – was quite inspiring. Yet if you tried to copy what he did, it was a disaster, so strong was his own musical personality. You had to translate all that into your own language. I learned not to take anything to him that I was about to play. He would attempt to impart so much information that I didn’t even know what the notes were any more.”

Asked about his own interest in teaching, Lewis demurred.

“No. Some years ago I had two students. I found it quite exhausting. I don’t know how anyone does it.”

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at CSO.org

- The compleat Paul Lewis: Visit his website

Tags: Alfred Brendel, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Harmonia Mundi, Jiří Bělohlávek, Vasily Petrenko