‘M. Butterfly’ at Court Theatre: Amorous fantasy blurs truth and tests the limits of plausibility

Review: “M. Butterfly” by David Henry Hwang, at Court Theatre through June 8. ★★

By Nancy Malitz

David Henry Hwang’s fantastical play “M. Butterfly” at Court Theatre begins as the imprisoned Frenchman Rene Gallimard relives his encounter long ago with a mesmerizing Peking Opera artist, who is performing a bit from Puccini’s opera “Madama Butterfly.” The artist plays a delicate geisha, tragically steadfast in love with an American naval lieutenant, who’s a cad.

As an “Oriental” experience goes, Gallimard’s fantasy once was typical of the East-West — and male-female — confusion that is the subject of Hwang’s intricate puzzle of a play set in Beijing and Paris of the 1960s and ’70s. This “M. Butterfly” — note the gender vagueness of that M. — is a new production by artistic director Charles Newell that stars Sean Fortunato as Gallimard and Nathaniel Braga as his sweet obsession and downfall.

Never mind that “Madama Butterfly” is a turn-of-the-century Italian opera, based on a French short story, starring a female soprano, who plays a young Japanese woman. It’s Chinese enough for Western visitors, or it was back then at least.

Never mind that “Madama Butterfly” is a turn-of-the-century Italian opera, based on a French short story, starring a female soprano, who plays a young Japanese woman. It’s Chinese enough for Western visitors, or it was back then at least.

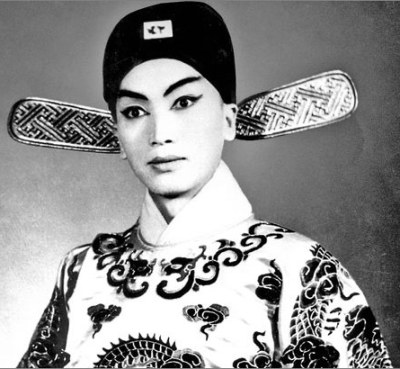

In fact, the opera bit was exactly the exotic ticket foreign visitors in Beijing expected to see, we are told by the Chinese man — Song Liling — whose Peking Opera-style performance drives Gallimard mad with desire.

Gallimard melds wholly into the fantasy of a new-age “Madama Butterfly,” with himself as the arrogant, all-powerful and (not least) sexually dazzling white westerner Lt. Pinkerton and this seeming-woman as the dainty, dependent, overwhelmed and adoring Oriental girl in the opera. (That’s Oriental as in subservient Asian.)

Thus it is that Gallimard — a shy, socially inept functionary in the diplomatic corps — begins a 20-year love affair with the man he believes to be a woman, his own little Butterfly, and falls into a classic honeypot lure for spy recruitment.

In a flashback, we see the diva cast a demure glance his way, and the helpless ex-pat is spellbound. A seductive espionage net is fine-tuned to Gallimard’s sexual preconceptions, and his diplomatic crimes, once discovered, become the love-blind Gallimard’s very public undoing. He is made the laughing stock of a show trial back in France.

In a flashback, we see the diva cast a demure glance his way, and the helpless ex-pat is spellbound. A seductive espionage net is fine-tuned to Gallimard’s sexual preconceptions, and his diplomatic crimes, once discovered, become the love-blind Gallimard’s very public undoing. He is made the laughing stock of a show trial back in France.

We live in a different world today, or do we? Broader sexual tolerance lessens the need for such deceit and self-delusion. Or does it? East and West, men and women, quite possibly understand each other better in the 21st century. Or do they?

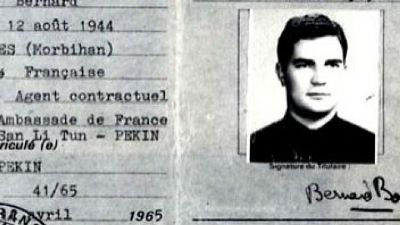

David Henry Hwang’s 1988 play amounts to a tragi-comic reverie on the infamous, hot-off-the-press accounts of the 1986 espionage trial of disgraced French civil servant Bernard Boursicot and Shi Pei Pu, the male Peking Opera singer who Boursicot insisted was female. A trial-ordered medical exam revealed the truth, and radio reports went out that “the Chinese Mata Hari, who was accused of spying, is a man.” Boursicot, shocked and despondent, went to prison for a year. He’s still living. Shi, also imprisoned briefly, died in 2009.

David Henry Hwang’s 1988 play amounts to a tragi-comic reverie on the infamous, hot-off-the-press accounts of the 1986 espionage trial of disgraced French civil servant Bernard Boursicot and Shi Pei Pu, the male Peking Opera singer who Boursicot insisted was female. A trial-ordered medical exam revealed the truth, and radio reports went out that “the Chinese Mata Hari, who was accused of spying, is a man.” Boursicot, shocked and despondent, went to prison for a year. He’s still living. Shi, also imprisoned briefly, died in 2009.

The tabloids have moved on. Hwang’s concepts are sufficiently broad and multi-faceted to allow for new interpretive reflections as time shifts the layers of art and artifice. Song gains in mordant wit: “What would you say if a blonde homecoming queen fell in love with a short Japanese businessman? He treats her cruelly, then goes home for three years, during which time she prays to his picture and turns down a marriage proposal from a young Kennedy. Then, when she learns he has remarried, she kills herself. Now, I believe you would consider this girl to be a deranged idiot, correct?”

The tabloids have moved on. Hwang’s concepts are sufficiently broad and multi-faceted to allow for new interpretive reflections as time shifts the layers of art and artifice. Song gains in mordant wit: “What would you say if a blonde homecoming queen fell in love with a short Japanese businessman? He treats her cruelly, then goes home for three years, during which time she prays to his picture and turns down a marriage proposal from a young Kennedy. Then, when she learns he has remarried, she kills herself. Now, I believe you would consider this girl to be a deranged idiot, correct?”

Gallimard, wallowing, seems more pathetic: “We, who are not handsome, nor brave, nor powerful, yet somehow believe, like Pinkerton, that we deserve a Butterfly.”

It must be harder than ever to sustain the plausibility of this agonized Frenchman while he tells his bizarre tale. Newell’s production is, however, sensually enveloped by Todd Rosenthal’s sets and Keith Parham’s lighting, and it affords one splendid glimpse into the magic of Chinese opera that Gallimard beheld — the dance of stylized combat choreographed by Jamie H. J. Guan, in which gorgeously costumed figures bearing lances advance and retreat in intricate patterns, evocative of pageant and mystery, that I would happily have watched for hours.

It must be harder than ever to sustain the plausibility of this agonized Frenchman while he tells his bizarre tale. Newell’s production is, however, sensually enveloped by Todd Rosenthal’s sets and Keith Parham’s lighting, and it affords one splendid glimpse into the magic of Chinese opera that Gallimard beheld — the dance of stylized combat choreographed by Jamie H. J. Guan, in which gorgeously costumed figures bearing lances advance and retreat in intricate patterns, evocative of pageant and mystery, that I would happily have watched for hours.

Fortunato’s flights of virtuosic gullibility were often reminiscent of Salieri’s madhouse rants in Peter Shaffer’s “Amadeus,” recalling the marvel and personal misery that was Mozart. Yet this over-driven Gallimard fails to capture the exquisite sweetness of the seduction that caused him so much pain.

The chemistry was off between Gallimard and Song Liling, despite Nathaniel Braga’s elaborate makeup, stunning costumes and mincing mannerisms. Song does not need to look drop-dead beautiful to our eyes; he is a man in woman’s guise. But he must seem irresistible to Gallimard, and that’s a different kind of trick to play.

Throughout Gallimard’s journey of what he believes to be self-discovery, he is urged along by a shadowy figure from his past who also provides much-needed comic relief. Thus the cavorting Mark L. Montgomery suggests a cross between the reckless bad boy Mac McMurphy in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and loopy Ed Norton in “The Honeymooners.”

Throughout Gallimard’s journey of what he believes to be self-discovery, he is urged along by a shadowy figure from his past who also provides much-needed comic relief. Thus the cavorting Mark L. Montgomery suggests a cross between the reckless bad boy Mac McMurphy in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and loopy Ed Norton in “The Honeymooners.”

As the bizarre relationship between Gallimard and his dream girl perks along, year after year, China is plunged into the cultural revolution and Song is shipped out to farm country for retraining. But then the party ideologues hit on the brilliant idea of sending this chap – the Chinese at least know he’s a cross-dressing guy – to Paris to resume espionage through Gallimard. When fissures rend the fantasy, the whole affair spirals toward the prison cell where the poor fellow, as heartbroken and abandoned as Butterfly ever was, tells his story.

Gallimard explains that he’d never been good with girls, so attention from this beauty quite floored him. He was in a sort of pro forma marriage at the time (the dryly austere Karen Woditsch as his wife), and readily turned away from that. Indeed, with his manhood newly roused, Gallimard even takes a tumble with a sexy little miss just arrived in Beijing from some blonde nation (Laura Coover). But his obsession with Liling is undiminished.

As the song goes, he only has eyes for her.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

Tags: Charles Newell, Court Theatre, David Henry Hwang, Karen Woditsch, Keith Parham, Laura Coover, M. Butterfly, Mark L. Montgomery, Nathaniel Braga, Sean Fortunato, Todd Rosenthal