Pianist Eschenbach, baritone Goerne plunge into churning stream of Schubert’s ‘Müllerin’

Preview: Frequent collaborators on Schubert’s tragic song-cycle “Die schöne Müllerin,” Christoph Eschenbach and Matthias George continue “inventing the music” at Orchestra Hall on Jan. 19.

Preview: Frequent collaborators on Schubert’s tragic song-cycle “Die schöne Müllerin,” Christoph Eschenbach and Matthias George continue “inventing the music” at Orchestra Hall on Jan. 19.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

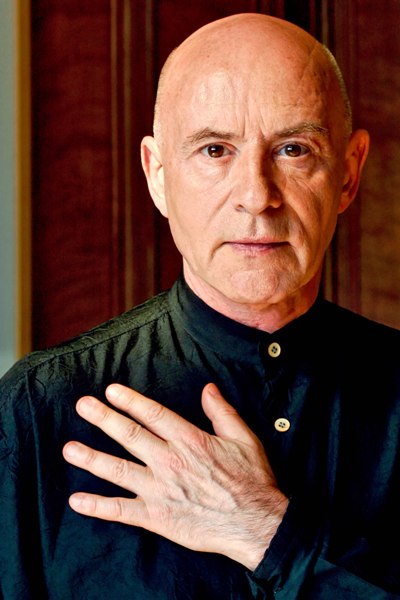

Baritone Matthias Goerne and pianist Christoph Eschenbach have collaborated many times on Schubert’s famous song-cycles – including the tragic “Schöne Müllerin,” which they will perform Jan. 19 at Orchestra Hall. It is an ever-evolving dramatic adventure, says Eschenbach, literally a flowing river which these two actors, baritone and pianist, can never experience twice in the same way.

“It’s a wonderful thing how it’s always new for us,” says Eschenbach in a conversation with Chicago On the Aisle. “You could say we’re inventing the music on stage as we go. We deal with it freely, and we take our cues from each other. We watch each other, listen to each other, trust each other. That’s what makes it so exciting, for us and I’m sure for the audience.”

“It’s a wonderful thing how it’s always new for us,” says Eschenbach in a conversation with Chicago On the Aisle. “You could say we’re inventing the music on stage as we go. We deal with it freely, and we take our cues from each other. We watch each other, listen to each other, trust each other. That’s what makes it so exciting, for us and I’m sure for the audience.”

The 20 songs of “Die schöne Müllerin” (The Beautiful Maid of the Mill) tell the story of a young journeyman miller who wanders over the countryside seeking his fortune. He follows a brook that leads him to a mill – and far more significant, the fair daughter of the miller.

Our wanderer falls in love with the girl, who scarcely gives the time of day to this youth of lower station. Then along comes a strapping huntsman, who instantly catches the girl’s eye. Heartbroken, the rejected suitor pours out his grief to the brook. The poor lad even imagines a romantic death for himself in which flowers spring up from his grave as symbols of his immutable love. But things only go from bad to worse until, in despair, he commits himself to the bosom of the brook, taking his own life.

“Each of the songs is a self-contained mini-drama,” says Eschenbach, the German-born music director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C., and frequent guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. “So the song-cycle becomes a big drama made up of small ones. This is fundamentally different from the large-scale architecture of Schubert’s symphonies or piano sonatas. Whereas a work like (Schubert’s) Great C major Symphony lies close to Bruckner in its sweeping design, the architecture of these songs is more intimate, more personal.”

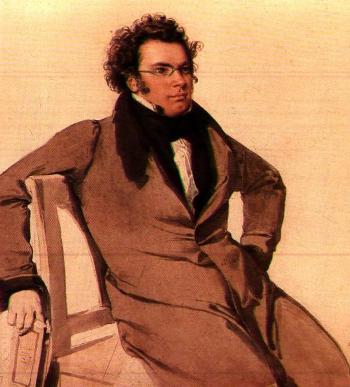

The Austrian Schubert drew his verses from a contemporary German poet, Wilhelm Müller, whose poems also would inspire Schubert’s later and no less celebrated song-cycle “Winterreise.”

Indeed, Schubert and Müller, who apparently never met, shared a good deal. Born just three years apart, Müller in 1794, Schubert three years later, they both died at an early age in the same year, 1827. And where Müller was fond of soirées in which he and other artists would share their new creations, the composer was famous for his musical evenings that came to be known as Schubertiades.

Indeed, Schubert and Müller, who apparently never met, shared a good deal. Born just three years apart, Müller in 1794, Schubert three years later, they both died at an early age in the same year, 1827. And where Müller was fond of soirées in which he and other artists would share their new creations, the composer was famous for his musical evenings that came to be known as Schubertiades.

Yet in a sense, observes Eschenbach, the similarities end there. If Müller was what we would call normally socialized, Schubert tended to be reclusive.

“The only time he got together with his friends was the Schubertiades,” says the pianist. “No doubt Schubert identified with the narrator in ‘Die schöne Müllerin.” It’s very personal for him. He was not a happy man. You hear this also in the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony, the painful and tormented imagery.”

What Eschenbach does not buy is the notion sometimes advanced that “Die schöne Müllerin” is a variation on the Faust story, that the wandering miller succumbs to the brook’s promise of love and happiness – only to be betrayed by his Mephistophelean rivulet, which ultimately snatches the lad’s life and soul.

“That’s totally wrong,” declares Eschenbach. “The river speaks to this wanderer in a very friendly way and becomes his companion. The Mephistopheles of the piece is the hunter, who never appears but is only talked about. The river is very dear, a sympathetic element.”

The creative challenge for both singer and pianist, he says, is to capture the individuality, the essence of each song, each little dramatic cell: “It is a complex atmosphere, with so many emotions, and you have to find the colors and musical gestures to describe that. This is the journey of a lonely and desperate soul, a man who wanders from place to place but cannot find peace.”

The creative challenge for both singer and pianist, he says, is to capture the individuality, the essence of each song, each little dramatic cell: “It is a complex atmosphere, with so many emotions, and you have to find the colors and musical gestures to describe that. This is the journey of a lonely and desperate soul, a man who wanders from place to place but cannot find peace.”

For Goerne and Eschenbach’s Orchestra Hall performance, seating will be added on the stage. The pianist welcomes that up-close and personal perspective.

“It’s nice. We had this in Vienna at the Musikverein, where the hall was packed and so was the stage,” he says. “It’s very intimate, though for the singer it is perhaps not so good because he often has his back to the listeners on stage. In fact, he’s usually looking at me to maintain eye contact. We stay so closely connected. We’re breathing together.”

Related Link:

- Performance location and ticket information: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Christoph Eschenbach, Die schöne Müllerin, Matthias Goerne, Schubert