Mahlerite Michael Tilson Thomas brings newly sharpened Ninth to Chicago Symphony podium

Interview: Music director of San Francisco Symphony, fresh from Carnegie Hall performance, calls Ninth Symphony a turning point for Mahler. Thomas leads concerts with CSO Nov. 21-24.

Interview: Music director of San Francisco Symphony, fresh from Carnegie Hall performance, calls Ninth Symphony a turning point for Mahler. Thomas leads concerts with CSO Nov. 21-24.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas is what G.B. Shaw might have called the perfect Mahlerite. Not only his baton but his heart as well beats to the subtle impulses of yearning, angst and mockery that permeate and shape Gustav Mahler’s epic creations.

Newly refocused on the subject, this Mahler maestro leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in four performances of the Ninth Symphony Nov. 21-24 at Orchestra Hall.

An old friend of the CSO, Thomas returns for this Mahler weekend fresh from a U.S. tour with his own San Francisco Symphony Orchestra that included a performance of the Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall in New York. I heard that idiomatic and intimately gauged account — which Thomas conducted from memory — and subsequently spoke with him about Mahler’s last completed symphony.

An old friend of the CSO, Thomas returns for this Mahler weekend fresh from a U.S. tour with his own San Francisco Symphony Orchestra that included a performance of the Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall in New York. I heard that idiomatic and intimately gauged account — which Thomas conducted from memory — and subsequently spoke with him about Mahler’s last completed symphony.

Perhaps owing to its long closing Adagio, which seems to hover at the doorstep of eternity, critics and commentators often characterize the Ninth as Mahler’s valedictory. Worn down by heart disease, the composer did not live to hear the Ninth Symphony performed. And yet he did muster the strength to turn immediately from orchestrating the Ninth to sketching his Tenth Symphony — a key indicator, says Thomas, that the irrepressible artist in Mahler was headed down a new path.

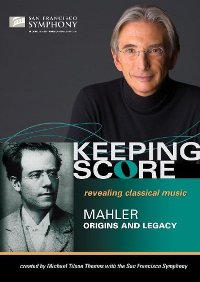

“I would prefer to think of the Ninth as the capstone, or the last chapter in an enormous cycle that goes all the way back to ‘Das klagende Lied,’” says Thomas, whose perspective on Mahler is documented on DVD in the San Francisco Symphony video series “Keeping Score.”

“I would prefer to think of the Ninth as the capstone, or the last chapter in an enormous cycle that goes all the way back to ‘Das klagende Lied,’” says Thomas, whose perspective on Mahler is documented on DVD in the San Francisco Symphony video series “Keeping Score.”

“From the beginning, Mahler’s symphonies are all closely related to one another, all of them linked to the world and culture of his childhood in Iglau (Moravia) and the village music he heard there as a boy — military music, cabaret, folk, the whole sociological phenomenon of music.

“It’s a story taken up from different points of view in different pieces. The Ninth Symphony brings all that to a close. It’s his most recognizably traditional symphony, written for a relatively modest orchestra with no voices. It’s a condensation of so many things he’s done before, but now with incredible skill and economy of means.”

Ill and tired as he was, says Thomas, Mahler plunged into the grandly conceived Tenth Symphony determined to re-invent his art.

“The Tenth is written in conjectural keys: D-sharp minor, for example, theoretically exists but it’s just too complicated to play with so many accidentals, double sharps and so forth. So it’s transposed for performance. But Mahler set about writing in such keys because he was trying to force himself to think in new ways — to force himself out of his comfort zone. He was moving on.”

“The Tenth is written in conjectural keys: D-sharp minor, for example, theoretically exists but it’s just too complicated to play with so many accidentals, double sharps and so forth. So it’s transposed for performance. But Mahler set about writing in such keys because he was trying to force himself to think in new ways — to force himself out of his comfort zone. He was moving on.”

If the unfinished Tenth poses overt technical pitfalls, the Ninth — whether singing, ruminative or riotous — is deceptively difficult, says the conductor:

“It’s an enormous challenge. Mahler is constantly setting up musical stunts that work, but they are hard to play. The second-violin part, just for example, is more difficult than any violin concerto.”

“It’s an enormous challenge. Mahler is constantly setting up musical stunts that work, but they are hard to play. The second-violin part, just for example, is more difficult than any violin concerto.”

What Mahler achieved dramatically with the Ninth, that last flourish in his old language, says Thomas, “is equivalent to what a master filmmaker does, someone like Fritz Lang. Or you might say the Ninth Symphony is like ‘Citizen Kane.’ So much is presented to you, details that you don’t completely tie together until you experience the end of the piece, and then you’re left awestruck that someone could imagine something like this.

“You’re confronted by this bewildering complexity of images, grand and trivial occurrences in a design you think you understand until you discover a completely different understanding. I often speak of great symphonic pieces as national parks. You’re back on familiar trail making new discoveries. You’ve changed since your last visit, maybe the light is different, or you’re there with a different companion.”

In a sense, the same might be said of Mahler revisiting the symphony on a long trail that led him eventually to a summit with the Ninth.

“The order of the movements is now changed, with an Adagio for the finale,” notes Thomas. “That took Mahler toward a different kind of completion. It’s preceded by a Burlesque, which is essentially a finale that you’d find in Haydn or Beethoven. But that done, Mahler is free to write a final movement in the singing style that was so essential to him.

“What he offers here is a continuous outpouring of confessional lyricism. In the end, it simply dissolves into nothingness. We have arrived in heaven.”

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Carnegie Hall, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Gustav Mahler, Michael Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra