‘Bengal Tiger’ at Lookingglass: Man, beast change stripes, and God’s not in the details

Review: “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” by Rajiv Joseph, at Lookingglass Theatre through March 17 ★★★★★

Review: “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” by Rajiv Joseph, at Lookingglass Theatre through March 17 ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

To be engulfed by the despair that sweeps over “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo,” which Lookingglass Theatre and director Heidi Stillman have turned into one of the peak stage experiences of this season, is to be reminded of the spiritual nausea that seized Jean-Paul Sartre and other French existentialist playwrights who watched their own world getting blown to pieces in the 1940s.

Set against a similar backdrop, America’s military invasion and occupation of Iraq, playwright Rajiv Joseph’s darkly imaginative “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” is so closely cut from the French existentialist cloth that it evokes a startling sense of déja-vu. Here again, but in modern guise and idiom, are the old – indeed, timeless – themes of man’s inhumanity to man, personal accountability and the problem of God.

Set against a similar backdrop, America’s military invasion and occupation of Iraq, playwright Rajiv Joseph’s darkly imaginative “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” is so closely cut from the French existentialist cloth that it evokes a startling sense of déja-vu. Here again, but in modern guise and idiom, are the old – indeed, timeless – themes of man’s inhumanity to man, personal accountability and the problem of God.

The tiger in question is a caged creature under guard by two U.S. Marines. There is this one small wrinkle: The tiger appears to us as a man, sizable, rotund and rather scruffy with long silver-gray hair and unkempt beard. This beast also talks – in a flowing, calm rumination on his imprisonment, the stupidity of lions and his own lethal nature. You might say he begins with the proposition that he is what he is, then meditates on why and seeks an answer from God, whose relationship to man and beast puzzles him and whose existence he comes to doubt.

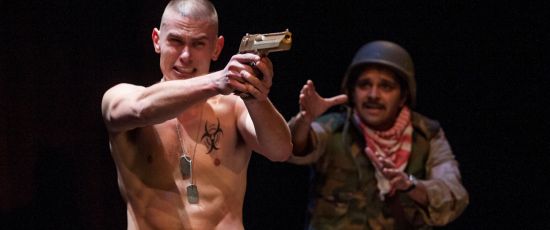

Events lurch forward when one of the soldiers tries to feed the tiger by extending a fistful of food through the bars. When the creature snaps off the guy’s hand, his comrade promptly shoots the tiger dead with a gold-plated gun his suddenly one-handed buddy has obtained as booty from the home of Uday Hussein, the vicious but now dead son of Saddam.

And so begins the repopulation of the stage with ghosts, starting with the tiger, which impassively haunts the young soldier who killed him. The second ghost we see is that of the late Uday Hussein, unrepentant and unredeemed. The prey of his earthly forays is his former gardener, Musa, who now works for the Americans as a translator. Something hideous transpired between these two men, back when Uday was in full evil flower, and it keeps replaying in Musa’s mind like some monstrous Groundhog Day.

And so begins the repopulation of the stage with ghosts, starting with the tiger, which impassively haunts the young soldier who killed him. The second ghost we see is that of the late Uday Hussein, unrepentant and unredeemed. The prey of his earthly forays is his former gardener, Musa, who now works for the Americans as a translator. Something hideous transpired between these two men, back when Uday was in full evil flower, and it keeps replaying in Musa’s mind like some monstrous Groundhog Day.

Meanwhile, the behanded soldier (played with John Wayne bravado by Walter Owen Briggs) returns to the scene to reclaim the golden gun, not to mention the gold toilet seat he also liberated from Uday’s residence. That creates some tension between him and his rather simple-minded pal (JJ Phillips in a performance of sad earthiness), who no longer has the weapon.

If the comedic potential is obvious, the laughter quickly turns edgy as playwright Joseph’s interconnecting circles begin to crush his characters. As the two Marines fall victim to their own folly, Musa the gardener – whom Anish Jethmalani brings to sympathetic life as much through eloquent gesture as through words — reels under the relentless, sardonic taunting of Uday’s ghost.

Uday, in the slickly attired and coolly maleficent form of Kareem Bandealy, presents a demon that the good soul Musa cannot exorcise: the embodiment of the ugliness that rules Musa’s world. As for the two Marines, they’re no better than self-interested plunderers, preoccupied with sex like any other young men and caught up like Musa in the paralyzing angst of this nonsensical war.

Uday, in the slickly attired and coolly maleficent form of Kareem Bandealy, presents a demon that the good soul Musa cannot exorcise: the embodiment of the ugliness that rules Musa’s world. As for the two Marines, they’re no better than self-interested plunderers, preoccupied with sex like any other young men and caught up like Musa in the paralyzing angst of this nonsensical war.

What is perhaps the play’s emblematic scene finds JJ Phillips’ young Marine searching an Iraqi home, confronted by a woman screaming at him in Arabic as her husband, a bag over his head and hands bound, kneels in silence. The equally frightened American soldier demands to know the contents of a low chest, then violently empties its cache of gorgeous scarves as the woman renews her incomprehensible chastisement. Musa the translator tries to help, but no one is listening. Pure terror reigns.

And all the while the phantasmical tiger – Troy West in a philosophically even-tempered turn – wanders the burning streets of Baghdad looking for answers, looking for God, and finding neither. Unlike Sartre, who abandoned that search, the patient tiger prowls on, though he reaches a conclusion not unlike the French existentialist’s:

And all the while the phantasmical tiger – Troy West in a philosophically even-tempered turn – wanders the burning streets of Baghdad looking for answers, looking for God, and finding neither. Unlike Sartre, who abandoned that search, the patient tiger prowls on, though he reaches a conclusion not unlike the French existentialist’s:

Sure, the voice of God eventually will resonate through all this mayhem, massacre and devastation. It will speak in a vernacular phrase common to English, Arabic and every other language – a stark, sobering, irreducible message of two words.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreinChicago.com

- Preview of Lookingglass Theatre’s complete season: Details at ChicagoOntheAisle.com

- Rajiv Joseph talks about the genesis of “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo”: Read the New York Times interview

Tags: "Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo", Anish Jethmalani, Heidi Stillman, Jean-Paul Sartre, JJ Phillips, Kareem Bandealy, Lookingglass Theatre, Rajiv Joseph, Troy West, Walter Owen Briggs

Beautifully written review, genius play I felt lucky to work on…

Beautifully written review, genius play I felt lucky to work on…