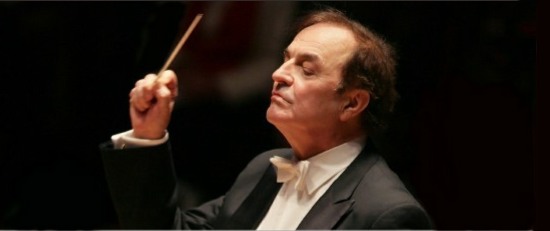

Conductor Charles Dutoit leads French lesson as CSO matches Impressionists with Dutilleux

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Charles Dutoit, conductor; Gautier Capuçon, cello. April 12-13 at Orchestra Hall. ****

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Charles Dutoit, conductor; Gautier Capuçon, cello. April 12-13 at Orchestra Hall. ****

By Lawrence B. Johnson

From the admixture of opulence and asceticism that constituted conductor Charles Dutoit’s program of French music with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra this weekend, one might have taken away good lessons offered in a perhaps subversively gleeful spirit.

First, with Debussy’s “Images for Orchestra,” we were reminded that France’s older partner in Impressionist crime was an orchestrator on the order of, well, the younger partner, Ravel. Secondly, with Ravel’s “La valse,” that wickedly wry paean to the Viennese waltz masters, Dutoit pointedly erased the hyphen that binds Debussy-Ravel into one super-sized composer in the Impressionist style. It did not take a fingerprint analyst to observe that “Images” and “La valse” were not penned by the same hand.

First, with Debussy’s “Images for Orchestra,” we were reminded that France’s older partner in Impressionist crime was an orchestrator on the order of, well, the younger partner, Ravel. Secondly, with Ravel’s “La valse,” that wickedly wry paean to the Viennese waltz masters, Dutoit pointedly erased the hyphen that binds Debussy-Ravel into one super-sized composer in the Impressionist style. It did not take a fingerprint analyst to observe that “Images” and “La valse” were not penned by the same hand.

Thirdly, and most illuminating of all, Dutoit provided a definitive answer to a question one might not even have thought to ask: What is the opposite of Impressionism? To a Frenchman, that is.

The answer came in Henri Dutilleux’s laconic 1970 cello concerto titled “Tout un monde lointain…,” translatable as “A whole distant world…” Dutilleux, who at age 96 resides in Paris, grew up and studied composition in the cultural hothouse that was France under le roi soleil Ravel. But after the mind-bending devastation of World War II, the mature Dutilleux threw over the Ravelian model and threw out everything he had written. Starting afresh, he cultivated a concise, spare and highly personal musical language that was scarcely recognizable as French and specifically not fashioned after Schoenberg and his Second Viennese school.

Exemplary of Dutilleux’s reformed style is this 25-minute cello concerto written in five continuous movements. Its title comes from poet Charles Baudelaire, whose death centenary “Tout un monde lointain…” honors. The young French cellist Gautier Capuçon offered an incisive, analytical account that captured the work’s peculiar stripe of neo-Classicism.

Exemplary of Dutilleux’s reformed style is this 25-minute cello concerto written in five continuous movements. Its title comes from poet Charles Baudelaire, whose death centenary “Tout un monde lointain…” honors. The young French cellist Gautier Capuçon offered an incisive, analytical account that captured the work’s peculiar stripe of neo-Classicism.

Reminiscent of the more austere side of Stravinsky, and even of Sibelius’ dark, efficient Fourth Symphony, Dutilleux’s “distant world” indeed keeps the listener at its periphery as its spins ever more inward. In their dialogue between cello and orchestra, Dutoit and the commanding cellist summoned a Platonic bearing: muted in gesture and persistently logical.

Dutoit and the CSO opened with the splashing brilliance of Debussy’s “Images,” playing out its dazzling orchestral tableaux from the ironically melancholy “Gigues” to the Spanish splendors of “Ibéria” to the sensuous whirl of “Rondes de printemps.” Dutoit’s elegant account drew equally on the music’s intricate rhyhms and its subtle voicing – glittering brasses and warm woodwinds cast against a fine sheen of strings.

At the concert’s far end came Ravel’s deliciously decade “La valse,” with its stretched and careening rhythms and earthy textures: ice cream and cake after Dutilleux’s Spartan fare. Here was the Vienna of Johann Strauss Jr. as viewed in a warped mirror – and darkly, at that. Dutoit indulged Ravel’s parody-homage to the hilt, and the CSO responded with a performance of hedonistic beauty.

Related Links:

- Profile of Henri Dutilleux: Read it here

- Profile of Gautier Capuçon: Read it here

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: Conductor Charles Dutoit (Philadelphia Orchestra photo). Descending: Celllist Gautier Capuçon (M. Tammaro Virgin Classics). Composer Henri Dutilleux.

Tags: Charles Dutoit, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Debussy, Gautier Capucon, Henri Dutilleux, Ravel