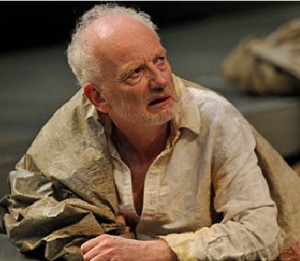

Ian McDiarmid, revving the engines of anger, ready to take on Shakespeare’s raging Timon

Preview: The Scottish actor, a Shakespeare veteran, talks with Chicago On the Aisle about the dark and turbulent mindscape of “Timon of Athens.” The play opens May 2 at Chicago Shakespeare Theater.

Preview: The Scottish actor, a Shakespeare veteran, talks with Chicago On the Aisle about the dark and turbulent mindscape of “Timon of Athens.” The play opens May 2 at Chicago Shakespeare Theater.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Imagine the vengeful anger of Shakespeare’s rebuked general Coriolanus superimposed on the mental extremity of King Lear, and you have a glimmer of the nihilistic madness that churns through the Bard’s less familiar alienation tragedy, “Timon of Athens.”

“Timon is delusional — obscenely rich, reckless and irresponsible,” says Scottish actor and Shakespeare veteran Ian McDiarmid, who plays the title role in the Chicago Shakespeare Theater production that opens May 2. “He refuses to deal with the fact that he has spent all his wealth until that reality is forced down his throat – and then he’s shocked and outraged when all his friends abandon him.”

“Timon is delusional — obscenely rich, reckless and irresponsible,” says Scottish actor and Shakespeare veteran Ian McDiarmid, who plays the title role in the Chicago Shakespeare Theater production that opens May 2. “He refuses to deal with the fact that he has spent all his wealth until that reality is forced down his throat – and then he’s shocked and outraged when all his friends abandon him.”

While McDiarmid has starred in centerpieces of the Shakespeare canon from “King Lear” and “Hamlet” to “Macbeth” and “The Merchant of Venice,” this is only the second time he has played Timon, and that earlier foray was years ago in a “concept” production he didn’t like very much anyway. (Speaking of long ago, and far away, it was McDiarmid who portrayed the evil emperor in the “Star Wars” film “Return of the Jedi” for George Lukas in 1983.)

For his second go at Timon, McDiarmid has worked with director Barbara Gaines to tighten and sharpen a drama that Shakespeare scholars agree was a collaboration between the Bard and the younger, highly regarded playwright Thomas Middleton.

In rough outline, the story is simple enough: The wealthy Timon has become the toast of Athens through his boundless largesse. He’s constantly throwing parties for his pals and showering them with gifts, until the day his steward Flavius finally makes him understand he has burned through his entire fortune down to the last drachma. Indeed, considerable debts have piled up.

No problem, replies Timon. He will tap his adoring circle for some cash to see him through. What are friends for? Timon quickly discovers that it’s easier to give than to get. His appeals for help are rebuffed on every side. Incredulous and enraged, Timon invites his erstwhile friends to one more banquet, where he serves them boiled rocks and lavishes them with vitriol – then storms from their midst and into the woods to become a hermit, like a dispossessed Lear who rages against the world and the perfidy of men.

No problem, replies Timon. He will tap his adoring circle for some cash to see him through. What are friends for? Timon quickly discovers that it’s easier to give than to get. His appeals for help are rebuffed on every side. Incredulous and enraged, Timon invites his erstwhile friends to one more banquet, where he serves them boiled rocks and lavishes them with vitriol – then storms from their midst and into the woods to become a hermit, like a dispossessed Lear who rages against the world and the perfidy of men.

Into Timon’s woods marches Alcibiades, a commander in the Athenian military now alienated much like Timon. A friend of Alcibiades has been condemned to death by the senate for killing a man, and the general has interceded on the friend’s behalf, invoking his own service to Athens as reason enough for the senate to honor his appeal. But all Alcibiades gains for his vehemence is banishment. Unlike Timon, who merely shrinks and shrieks, Alcibiades turns his fury to a purpose: Just as Coriolanus brings his wrath and his army down upon Rome, Alcibiades now threatens Athens.

The wrinkle in all this is that Timon, digging in the woods for roots to eat, unearths a cask of gold coins, which he lavishes on all those who visit him, with the stipulation that they use this treasure to spread ill-fortune in the world – and then hang themselves. He happily funds Alcibiades’ military campaign against their mutually estranged countrymen.

“Timon is at the end of his tether when he enters the woods,” says McDiarmid, “but he finds his imagination reawakened by the possibilities of doing terrible things. This really puts a dark twist on the Shakespearean retreat into the woods, where good changes usually happen – in ‘As You Like It,’ for example. But this is a cheerless landscape.”

McDiarmid doesn’t see Timon as the abused victim of fair-weather friends, a man driven off his base by unbearable circumstance.

“He’s probably psychotic. You just want to shake him,” says the actor. “In Act I we already see him refuse to accept repayment for a substantial loan. He waves it off as if to take repayment would somehow compromise his act of generosity. It’s really a perverse ploy. He’s out of touch with reality. That’s why he has never listened to Flavius’ warnings that his fortunes were depleted.”

McDiarmid and director Barbara Gaines have relocated the play to contemporary America, and re-ordered the series of wilderness encounters between Timon and his visitors to relieve what McDiarmid describes as “this prodigious rant.”

Monomaniacal as the play’s latter stages may seem, they at least bear the sure edge of Shakespeare’s pen. Scholars generally agree that the setup scenes in Timon’s home – what McDiarmid calls the “urban part” – are more likely the work of co-author Middleton. But Timon’s raging invective, a Shakespeare specialty, is the Bard at his rapier best.

“The play’s second half is a rebirth in nihilism,” says McDiarmid. “It’s Beckett: We are born ‘astride of a grave.’”

The whole quote, from “Waiting for Godot,” is: “They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” That’s “Timon of Athens.” Existential Shakespeare.

Related Links:

- “Timon of Athens” analyzed as satiric comedy: Read it here

- Learn more about Ian McDiarmid: Visit his website

- The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust is inviting everyone to blog, tweet or make a video in honor of the Bard’s birthday: Find out how here

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: Actor Ian McDiarmid. Descending: If stock prices are rising, Timon (Ian McDiarmid) sees no cause to stem the flow of his largesse. Timon (Ian McDiarmid) hits bottom, with nothing left but his rage. Below: Director Barbara Gaines talks with McDiarmid about condensing “Timon of Athens” for clarity and about the idea of failure in the play.

Tags: "Timon of Athens", Barbara Gaines, Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Ian McDiarmid, Shakespeare