Chicago Shakespeare: Solving the ‘problem,’ but creating others, in ‘Measure for Measure’

Review: “Measure for Measure” by William Shakespeare, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater through Nov. 27. ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

If Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure” is a comedy, as it is often tabbed by scholars, it is a very dark one. Though it’s not without real laughs, as Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s new production generously demonstrates, “Measure for Measure” might just as plausibly be called a morality play. That would not be so far from the conventional term for it as a “problem” play, meaning it is neither comedy nor tragedy (nor history, to be sure), but rather centers on a complication that’s resolved at the final curtain.

CST’s aggressively distilled “Measure for Measure” is a light version that brings to mind the Metropolitan Opera’s condensed, English-language version of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” readily consumable by the whole family. (Not here, though.) In the case of “Measure for Measure,” there’s an argument for boiling it down to essential lines and action. There’s probably an argument for not doing the play at all, but at least this treatment directed by Henry Godinez skips along at a good clip, extracting lively theater from a rather ponderous “lesson” text.

“Measure for Measure,” dating from 1604, is the last of three such problem plays written consecutively, after “Troilus and Cressida” and “All’s Well The Ends Well.” Also usually placed in this head-scratching category are “Timon of Athens” and “The Winter’s Tale,” both later. In quite a pivot, Shakespeare would next pen, sequentially within just a couple of years, the great tragedies “Othello,” “King Lear” and “Macbeth.”

The original setting of “Measure for Measure” is long-ago Vienna, which has fallen into a debauchery that’s largely ignored by the regime of the governing Duke. But the Duke decides to make his own assessment of the city’s life by disguising himself as a monk and walking among his people. He leaves full interim authority to his deputy Angelo, a famously upright fellow and one now resolved to clean up the town. Angelo immediately arrests the young swain Claudio on the charge of fornication, for getting Claudio’s betrothed Julietta pregnant. The penalty is death.

Claudio gets word to his sister, the novice Isabel, pleading for her to save him. She confronts Angelo and argues for her brother’s basic goodness. But there’s no help for it. The law is the law, Angelo declares, and Claudio must die the next morning. As Isabel presses her case, however, the stern deputy discovers he’s having a binary reaction. He offers a deal, a sweeter version of an eye for an eye. The novice, appalled, goes straight to her imprisoned brother and lays out Angelo’s lewd proposition. To which Claudio replies, in essence: “That’s it? That’s all you have to do and I’m outta here?” Isabel tells him, and not figuratively, to drop dead. And so commences a progress of general redemption, wherein all is made right, measure for measure.

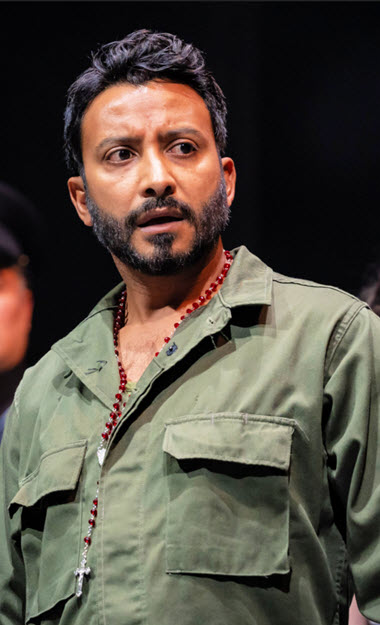

CST has relocated the action from dim Vienna to vivid, decadent mid-20th-century Havana, which we see encapsulated in a pre-show cabaret scene, complete with songsters and showgirls and an ample, middle-aged guy cavorting in just his skivvies and a wide-brimmed hat. We also catch our first glimpse of Angelo, not yet so identified but unmistakable in his recoiling from the nasty stuff going on around him. And he’s clad entirely in the olive-green of the people’s army. Is this righteous figure the young Fidel Castro, or perhaps Che Guevara?

In any case, the high-minded deputy soon receives the scepter of the city and full governing authority from the withdrawing Duke, whom alas we will see too little. Whether in official uniform or concealed beneath a monk’s robe, Kevin Gudahl is the dramatic pillar of this production, a Shakespearean who delivers his speeches with a purpose. He is articulate, expressive, credible, a pleasure at all times. Shakespeare rises or falls with the text; trappings are secondary. Gudahl is the soul of simplicity and directness. He wears his habit wisely.

HIs matches here are both on the comic side. Elizabeth Ledo, a sublime comedian and knowing Shakespearean, is a sly delight as the clown Pompey, street-smart in the game of self-preservation, ever adaptable to fortune’s flow. Likewise charming, though not wise at all, is Gregory Linington’s bragging, mendacious, imprudent and always overstepping Lucio, best friend to the imprisoned Claudio. Again and again, Lucio reviles and impugns the Duke, whether unwittingly addressing him in his monkish guise or in speaking to the Duke about that scurrilous monk. It’s something of a vaudeville shtick, but Linington’s fulminations are so earnest, as brash as they are phony, that it’s all very funny.

Still, the key to “Measure for Measure” is the grim contest between Angelo and the novice Isabel. There must be rising heat on his side, expressed through text in the voice, and countering evasion turned horror on her side. Both Adam Poss and Cruz Gonzalez-Cadel gave more the impression of reading, and not quite convincingly at that. His physical awakening was amusing, but we never really connect with the man as imperious prude, much less one deluding himself in that posture. Her speeches came across generally as strident and monotonal, ultimately shouted rather than searing.

Evocative sets by Rasean Davonte Johnson and colorful costumes (only Angelo wears olive) by Raquel Adorno give the show an aspect that’s lavish, integrated and altogether fresh.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheaterInChicago.com