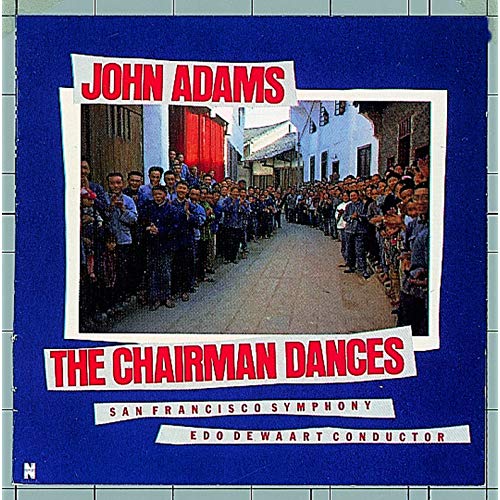

Like John Adams’ ‘Chairman,’ the CSO dances (and Stravinsky’s fiery Violin Concerto sizzles)

Long ago, conductor Edo de Waart showcased music of John Adams, then unknown. One of these 20th-century gems, still sparkling, kicked off a Chicago Symphony concert. (©Jesse Willems)

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Edo de Waart conducting, with violinist Leila Josefowicz, through Dec. 22.

By Nancy Malitz

With the bubbling impertinence of John Adams’ foxtrot for orchestra, “The Chairman Dances,” the air turned absolutely electric in the holiday crowd at Orchestra Hall, which was stacked with a younger than usual audience mix on Dec. 19 for a Throwback Thursday to remember. The world’s largest instrumental music education conference was underway in Chicago for its 73rd year, with many student musicians in attendance. Were these fellow travelers ever in for a treat:

On the Chicago Symphony podium was Dutch conductor Edo de Waart, who discovered the then unknown classical superstar Adams in San Francisco in the 1970s, when De Waart was music director there and recorded many of his pathbreaking early pieces including this one. How delightful it was to witness, before the concert even began, the grins on the faces of assistant concertmasters David Taylor and Yuan-Qing Yu as they ran through some of Adams’ tricky stuff, lickety-split and in unison.

Adams’ heady sequence of insistent, rakish minimalism is now quite familiar, but it was written at a time when the highly esteemed composer, now 72, was still introducing his hypnotically repetitive style, and as he was ramping up to work with theater director Peter Sellars on the audaciously disruptive opera “Nixon in China.” Adams developed the idea of a slinky dance scene for Madame Mao, who gate-crashes Nixon’s chopstick diplomacy at a Chinese state banquet and makes the moment all about herself. The strangely alluring music shimmers with expectancy and thrives on the most intricate rhythmic shifts, subtle bursts of color, and bizarrely perky filigree. It was great fun to hear De Waart and the Chicagoans sustain such an extended dreamlike seduction. (Adams would handle the music differently in the complete opera, and Madame Mao’s intrusion becomes a full-scale melee to different music, which you can check out in the video at the bottom of this review.)

The eventual Adams-Sellars opera, which hit the stage two years later in 1987, caused an intellectual rift only somewhat more civilized than the near riot in 1913 Paris over Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring.” What a stroke of brilliance, then, to program Adams’ work side by side with Stravinsky’s own Violin Concerto in D, performed by the irrepressible Leila Josefowicz, a trailblazer in her own right. She performs new music ferociously, spectacularly, and almost exclusively. In fact, the Stravinsky, from 1931, is her one and only golden oldie. Rarely has the first half of any concert delivered a more exhilarating blast.

But we’re on the other side of some history now: When “Nixon in China” debuted, the most powerful newspaper critic of the day complained that “Mr. Adams does for the arpeggio what McDonald’s did for the hamburger, grinding out one simple idea unto eternity.” In 1991, when he was already a star ascendant, Adams, still miffed, told me “it’s the sort of thing you have to put up with, year after year, until these people finally get sent to the glue factory and somebody else comes in, … or, more likely, until some younger composer comes along that they can hate even more.”

Adams stuck to his guns, along with a group of American composers who were ready to shuck off their mid-20th-century European dads and write music according to their own rules.

They were not alone: All one has to do is hear the stunning impact of the single opening violin chord at the beginning of the Stravinsky concerto, a pile-high dissonance just bristling with primal possibility, to understand that for this fiercely original composer there would be no constraining ancestral formula. The Stravinsky was a fabulous showcase for Josefowicz, but it’s hardly a concerto in the Romantic sense, or even in the Baroque sense, despite the many episodes with players in twos and threes that call to mind Bach’s concerti grossi. Josefowicz made an exquisite, brooding poem of the third movement, an “aria,” that was an island unto itself. There was nothing old or quaint about it.

The explosion of energy that constituted Josefowicz’s finale amounted to nothing I had experienced in this work previously – a gleeful physical abandon that might have seemed reckless in other hands. Instead, she conveyed the effortless exuberance of a virtuoso who just wanted to draw you in – with a smile that said, “Did you catch that?” and the raised eyebrow that said, “Can you believe this?” and the forward drive that kept promising more. All at incredible speed, with enormous strength and bravado.

Perhaps it was too much to expect, on a program like this, that a second half devoted to Dvořák favorites – the “Carnival” Overture and the Eighth Symphony – would match the tremendous impact of the Adams and Stravinsky works. Dvořák himself conducted the Eighth Symphony in Chicago in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition, so there was a certain sense of history in the occasion. And indeed, the two beloved Romantic pieces traced their familiar brilliant contours in reliable ways. But mostly, they seemed loud and fast to me.

Related Link:

- Performance and ticket info: Details at CSO.org