‘The King’s Speech’ at Chicago Shakespeare: In his personal storm, a monarch finds a port

The recumbent Albert (Harry Hadden-Paton) is joined by his wife (Rebecca Night) in a novel speech therapy session led by Lionel Logue (James Frain). (Liz Lauren photos)

Review: “The King’s Speech” by David Seidler, directed by Michael Wilson, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater through Oct. 20. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

It’s the most improbable of buddy plays, David Seidler’s “The King’s Speech.” It just happens to be true, and its essential humanity is on captivating display in a masterful production at Chicago Shakespeare Theater.

The most common of commoners, an obscure Australian speech therapist on an extended visit to London, is confronted by the most regal of royals: the soon to be crowned George VI of England, who suffers from a lifelong stutter and will find himself thrust into the roiling vortex of a world on the brink of war.

As conflict looms with Hitler’s Germany, England looks to its King for reassurance – a message of resolve and confidence to be delivered across the far-flung realm by radio. Which means the afflicted King needs help in the most desperate way.

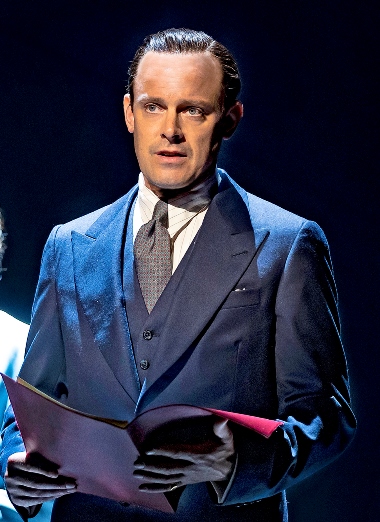

What plays out between the proud yet terrified King (the majestic and vulnerable Harry Hadden-Paton) and his self-taught, insightful, straight-shooting therapist (James Frain conveying all of that plus a good measure of wit) is progress by fits and starts towards self-knowledge in the King and a trust that ascends to friendship.

A bit of background is in order. Before he became His Royal Highness, George VI was Prince Albert, Duke of York, son of George V and younger brother to David, Prince of Wales. Upon the death of their father, David inherited the throne of England. But David, a bit of a bounder, was more interested in an American divorcée called Wallis Simpson – and, to the general relief of Brits everywhere, abdicated in order to marry the woman, who was never going to be accepted as, oh my, Queen.

That made Albert the next man up. Let us now return to history refitted as Seidler’s play. In every respect but one, Albert – or Bertie, his nickname in the family – is fully up to kingship. He is highly intelligent, dutiful and caring. His wife Elizabeth (Rebecca Night) knows this very well; indeed, when alone with Elizabeth, Albert exhibits no speech impediment whatsoever. But he has always stammered around his own family (his brother David continues to mock him for it), and in public he can scarcely get through a sentence without severe stuttering.

To be sure, Albert has worked with therapists before, several, all without meaningful benefit. His wife hears about this young Australian, Lionel Logue, who has had some success helping others. She seeks him out, talks with him and finally says, OK, you may come to consult with the King.

Uh, no. Lesson No. 1 for their royal highnesses: Lionel’s patients come to him. As he puts it, and not for the last time – his house, his rules.

And so begins a marvelous series of, well, clashes between Frain’s very smart, experienced and unswerving speech therapist-cum-psychiatrist and Hadden-Paton’s reluctant and importuned monarch, a man reeling, perhaps more imperiled than imperious. Lionel insists that the King call him by his first name. But what shall the therapist call the King? Your Highness won’t do in this relationship, Lionel says. The King must have a given name; what is it? Albert, concedes the King. No, no. What does your family – your wife – call you? The King gives it up: Bertie. And that is what Lionel calls him.

These vital early exchanges, thorny on the King’s side and cheerfully insistent on Lionel’s, are played to a fare-thee-well by Frain and Hadden-Paton. Thus their relationship becomes credible. The King’s need is great, and in spite of himself he sees the efficacy of Lionel’s method.

Their eminence notwithstanding, Albert (Harry Hadden-Paton) and his wife (Rebecca Night) must wait until Lionel (James Frain) is ready for them.

Almost immediately, the therapist turns to quasi-Freudian analysis, probing into his patient’s royal childhood, which was something less than happy. No one comes into this world stuttering, Lionel observes. At first the King, indignant at such presumptuous questioning by a commoner, pushes back fiercely. But then he answers; more to the point, he owns the painful truth of his answers.

It’s good stuff, and quite touching.

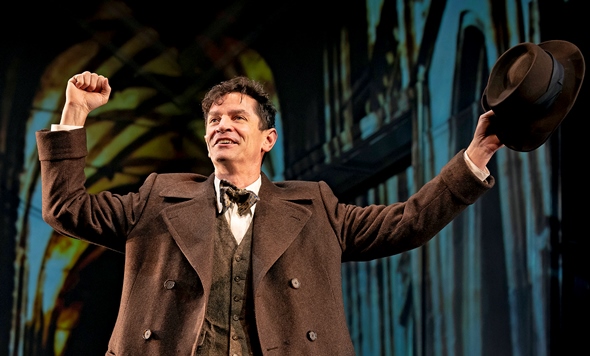

Neither the King’s pursuit of relief nor Lionel’s side street practice occurs in a vacuum. Lionel, who has enjoyed some small-time success as an actor back in Australia, yearns for a shot at the London stage. Glimpsing him at two auditions, we see that his natural gifts as therapist are not mirrored in his acting prowess. Meanwhile, he’s being pestered by his wife (Elizabeth Ledo), who just wants to go home to their normal, anonymous life down under.

The King’s personal crisis is expressive of a national turning point. The specter of war has the government on edge. First, there’s the internal crisis of David’s obsession with Wallis Simpson; and when David himself removes that problem, by waving off the crown, there’s still the conundrum of a new king who couldn’t order fish and chips without stuttering. The dilemma of Albert makes for some highly theatrical ruminations between Kevin Gudahl’s deft, wry Winston Churchill and Alan Mandell’s airily arrogant Archbishop of Canterbury.

Therapist (James Frain) and King (Harry Hadden-Paton) share good wishes as the young man’s wife (Elizabeth Ledo) looks on.

For my money, the best comes last, in the final two scenes – the first an absolute blow-up by the King upon discovering that Lionel is no doctor at all. (He never said he was.) It isn’t so much the King’s rage as Lionel’s rejoinder that disarms us, even as it gives His Royal Highness pause.

The payoff is the King’s speech to the English people. Hadden-Paton’s delivery is a tour-de-force of acting. The speech is not impeccable, effortless, miraculous. It is willed, painstaking, hesitant but hell-bent. In a sort of Churchillian manner of measured rhetoric, one might even say it is eloquent.

Kevin Depinet’s sets, abetted by Hana Kim’s projections and Howell Binkley’s lighting, are eye-catching. The cluttered shelves in Lionel’s studio surely would give any monarch second thoughts about seeking refuge there. But the result bears out the maxim: Any port in a storm.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com