‘King Lear’ at Redtwist: The existential Bard, pared to the core of being – and nothingness

Review: “King Lear” by William Shakespeare, at Redtwist Theatre through Aug. 4. ★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Redtwist Theatre, the fearless vest-pocket company in Edgewater, winds up its season, the last for co-founder and artistic director Michael Colucci at the helm, with its first venture into Shakesespeare: a lean, uneven “King Lear,” but one altogether imposing in Brian Parry’s assured, fierce and affecting performance in the title role.

Kent (Cameron Feagin, left) and Gloucester (Darren Jones) remain faithful to the careening King Lear.

The plays of Shakespeare constitute an art-form unto themselves, and a life’s evolutionary work for actors. In any case, a drama the likes of “King Lear” unequivocally points up the accomplished players alongside those who are less so; for the young who would strut the stage, Shakespeare is trial by fire. This Redtwist go at “Lear,” directed by the veteran Steve Scott, displays all of that – the stagecraft and the flames.

To believe in Shakespeare’s apocalyptic tragedy of a vain king who, as his Fool observes, grew old before he grew wise, we must see before us an aging monarch lost within himself, an all-powerful man desperately needful of assurance that he is loved – and blinded by his consuming vanity. Lear hands over all of his authority and his treasury to two daughters who have gushed their protests of devotion, only to turn on him and neutralize him and cast him into the teeth of a violent storm.

“Lear” is a proto-existential play. It brings to mind Jean-Paul Sartre’s exegesis “Being and Nothingness.” Like blindness, the conceit of emptiness – nothingness – runs through the play as a central leitmotif. Lear’s daughter Cordelia, the only one of his children who truly loves him, refuses to join in the great posturing of piety that he requires before deciding how to apportion his kingdom. When Cordelia answers his fond – in the old sense, foolish – query as to what terms of affection she might lavish on him to outdo her older sisters, she replies: “Nothing.” And he, astonished, shoots back: “Nothing will come of nothing: speak again.”

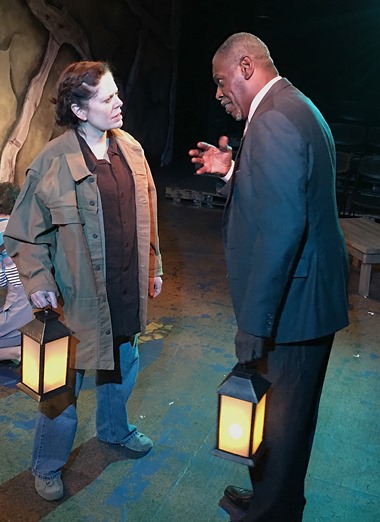

Lear’s daughter Goneril (Jacqueline Grandt) sees more than political potential in lusty young Edmund (Mark West).

From this springboard of discontent, Lear launches himself into the maelstrom of his own bitter destruction. Parry draws us there in a potent performance whose scope far exceeds the closet boundaries of Redtwist’s ever challenging space. When the turned-out Lear embraces the night’s raging tempest, Parry summons an emotional torrent worthy of adversarial nature. We watch him disintegrate, and we subscribe to his conviction that a poor, half-naked, babbling idiot he encounters on the heath must also be the victim of heartless daughters. Parry’s evocation of Lear as disillusioned king and amazed fool, as clear and concentrated as it is urgent and despairing, captures Shakespeare’s language as a monumental cri de coeur.

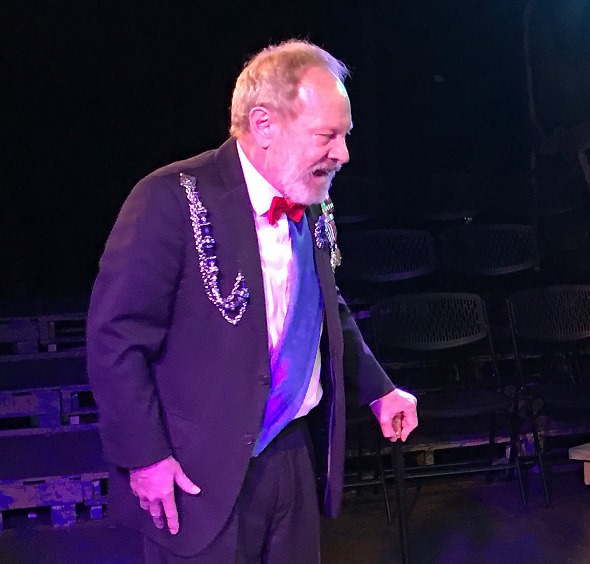

The rest is variable. Along with some fine supporting performances are marginal efforts and one highly problematic directorial choice. Scott has turned Lear’s stalwart adviser and undying friend the Earl of Kent into a woman. Not just played by a woman, but represented as a woman. To impute feminine gender to the right-hand-man of a king in some period of the remote past is to torment plausibility into the corset of modernism. That said, Kent, who tries to dissuade Lear from rashly disowning Cordelia, is swiftly banished, only to disguise himself as a rough character and insinuate himself back into the King’s service. In that guise and hard manner – she’s now suddenly a man! — Cameron Feagin makes a very appealing and sympathetic Kent.

The King’s newly empowered daughter Regan (KC Karen Hill) might leave her husband Cornwall (Scott Buechler) in the shadows.

Two other actors also bring full command to their work: Jacqueline Grandt, as Lear’s eldest daughter, Goneril, not only imbues her haughty persona with an imperious voice but she also never slips from character even when looking on from the shadows. And Darren Jones offers a ringing portrait as the Earl of Gloucester, a good soul but a man as blind as the King when faced with the deception of a bastard son’s effort to sideline his better brother.

After that, this “Lear” begins to feel cobbled together. Mark West, as Gloucester’s bastard son Edmund, is articulate and decisive but his driven speech is all of a piece, wanting modulation and calculation. Like West, Robert Hunter Bry brings the needed youth to his portrayal of Gloucester’s legitimate son Edgar, and he makes an animated effort as Poor Tom – Edgar’s mad disguise when he flees his father’s house on false accusations by Edmund. But Poor Tom is a deceptively hard role to bring off, and Bry’s energy goes unmatched by his range.

At least at the performance I saw, KC Karen Hill acted the part of Lear’s other unkind daughter, Regan, at something of an intense sotto voce. Much was lost in that power outage. As for Lear’s devoted Fool, as touching a character as may be found in Shakespeare, Liz Cloud’s perky speech and light step barely placed her in the realm of marvelous possibilities. The three remaining principals — Kayla Raelle Holder as Cordelia, Scott Buechler as Regan’s husband Cornwall and James Hesla as Goneril’s husband Albany – all served creditably.

Modern dress was forgiving of modest costumes, and the production’s generally meager aspect perhaps only turned attention back to the players – rather like a reading, with movement.

But I would not hesitate to catch Brian Parry’s Lear in one of the remaining performances. It’s not about sets. It is a personal declaration, intelligent and honest, at once polished and unvarnished. The author would recognize his sorry old monarch.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com