August Wilson’s legacy resonates in vitality of African portraiture by playwright Danai Gurira

American playwright Danai Gurira’s play “The Convert,” which began with her wish to write an African “Pygmalion,” explores the effects of colonialism in her ancestral Zimbabwe.

By Nancy Malitz

All 20 precociously accomplished high school actors who recently took part in the August Wilson Monologue Competition at the Goodman Theatre were offered free tickets to American playwright Danai Gurira’s “The Convert,” onstage at the Goodman through March 25.

I hope they took the Goodman up on it. The late August Wilson’s legacy is strongly present at the Goodman this month.

Wilson would have been encouraged to find these teenage actors on such comfortable terms with his monumental 10-play cycle about the 20th century African American experience. Boy Willie, Memphis, Rose and Hedley are as vivid and real in these young actors’ imaginations as Hamlet, Jaques and Juliet.

Wilson would have been encouraged to find these teenage actors on such comfortable terms with his monumental 10-play cycle about the 20th century African American experience. Boy Willie, Memphis, Rose and Hedley are as vivid and real in these young actors’ imaginations as Hamlet, Jaques and Juliet.

And Wilson would have been excited by Danai Gurira’s wannabe priest, Chilford, and the six other sharply-etched black characters in “The Convert” who are living life to the full in late 1895-97 Salisbury on the Zimbabwean plateau -– an area newly named Southern Rhodesia, where the Shona people and their neighboring tribes are undergoing swift British colonization.

And Wilson would have been excited by Danai Gurira’s wannabe priest, Chilford, and the six other sharply-etched black characters in “The Convert” who are living life to the full in late 1895-97 Salisbury on the Zimbabwean plateau -– an area newly named Southern Rhodesia, where the Shona people and their neighboring tribes are undergoing swift British colonization.

Gurira introduces her characters with high wit put to most serious purpose, an examination of the exhilarating and brutal clash of cultures from the viewpoints of all seven of these Africans. And in doing so, she is standing on Wilson’s shoulders.

Gurira is perhaps best known to Americans as Jill in “Treme,” the recent HBO series set in post-Katrina New Orleans. She has also been signed as Michonne, a hooded, sword-wielding heroine who will appear in AMC’s zombie drama “The Walking Dead” next season.

Gurira is perhaps best known to Americans as Jill in “Treme,” the recent HBO series set in post-Katrina New Orleans. She has also been signed as Michonne, a hooded, sword-wielding heroine who will appear in AMC’s zombie drama “The Walking Dead” next season.

All this, in addition to being a playwright of considerable emerging power. (After finishing in Chicago, “The Convert” moves on, strong cast intact, to the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles starting April 17. The production, under the elegant direction Emily Mann, originated at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre Center. Mann is seen below as she and Gurira talk about the play’s gestation.)

Gurira was born in Iowa to Zimbabwean parents, both academics, and she spent 14 years of childhood in Zimbabwe before returning to the U.S. for college and graduate studies. Zimbabwe’s capital is Harare, once known as Salisbury, the colonial headquarters where “The Convert” is set.

Gurira was born in Iowa to Zimbabwean parents, both academics, and she spent 14 years of childhood in Zimbabwe before returning to the U.S. for college and graduate studies. Zimbabwe’s capital is Harare, once known as Salisbury, the colonial headquarters where “The Convert” is set.

Like Wilson, Gurira has expressed a desire to come to terms through a cycle of plays with her own identity as a woman of African, American and Christian heritage. (Her 2010 play “Eclipsed,” about Liberian women captives in war, won several national awards and was produced at Northlight Theatre last season. Other notable contemporaries of Gurira including Lynn Nottage are traveling similar paths.)

Like Wilson, Gurira has expressed a desire to come to terms through a cycle of plays with her own identity as a woman of African, American and Christian heritage. (Her 2010 play “Eclipsed,” about Liberian women captives in war, won several national awards and was produced at Northlight Theatre last season. Other notable contemporaries of Gurira including Lynn Nottage are traveling similar paths.)

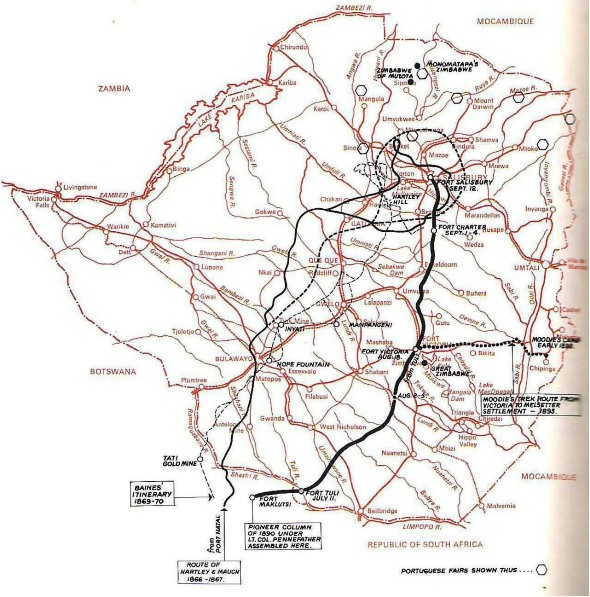

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in south central Africa, bordered on the northwest by Victoria Falls and by Mozambique to the east, South Africa to the south, Botswana to the west. “The Convert” is set amid the great South African land grab brought on by the discovery of diamonds and gold in abundance, for which Britain, Germany and Portugal were all competing. The Boer Wars, between Britain and the descendants of the Dutch, lay just a few years ahead.

But that’s already more history and geography than the average American playgoer has in command, and it’s to Gurira’s credit that she builds history’s critical moment outward from the perfectly understandable passions and predicaments of seven memorable characters.

The story begins as a headstrong 16-year-old Musezuru girl, Jekesai, desperate to escape a forced marriage arranged by her uncle, is brought to the English-style home where her aunt works as housekeeper. The girl is sheltered there by Chilford, a well-educated, English-speaking Roman Catholic convert who is enamored of the purity and wisdom of his adopted faith. He is also giddy with happiness to identify himself with the white culture that gave it to him.

The story begins as a headstrong 16-year-old Musezuru girl, Jekesai, desperate to escape a forced marriage arranged by her uncle, is brought to the English-style home where her aunt works as housekeeper. The girl is sheltered there by Chilford, a well-educated, English-speaking Roman Catholic convert who is enamored of the purity and wisdom of his adopted faith. He is also giddy with happiness to identify himself with the white culture that gave it to him.

Chilford renames Jekesai as Ester and proceeds to share his religious zeal in rapid streaks of non-colloquial English. The charm of these early scenes is undeniable, as when Chilford is explaining to Ester’s skeptical aunt why the girl must have lessons: “Why school? You are not in seriousness! She is sunken in the deepest deep of barbaric practices that is of why! We are trying to civilize our people Mai Tamba! How is that going to happen if she is not steeped in the most potent marination of Biblical and academic studies?”

Chilford’s petite bourgeoisie friend Chancellor is an even more conspicuous imitator of the Colonial class, if somewhat impatient with Chilford’s spiritual aspirations: “No buts to be had old boy! I am helping you grow on the ladder of prestige – we are still a rarity – African and highly educated – you best be in obedience to my wise ideals or die a pauper!”

Chilford’s petite bourgeoisie friend Chancellor is an even more conspicuous imitator of the Colonial class, if somewhat impatient with Chilford’s spiritual aspirations: “No buts to be had old boy! I am helping you grow on the ladder of prestige – we are still a rarity – African and highly educated – you best be in obedience to my wise ideals or die a pauper!”

And Chancellor’s fiancée, Prudence, loves her pipe and her English tea, but is also wary of village politics: “I have been very good to everyone, very good. I still speak the bloody vernacular, unlike Chilfy, the Great Black Tragedy.”

At the center are four Shona people struggling to come to terms with the opportunities and dangers the white man brings:

Ester, deeply grateful for escape from marriage to an old man with 10 wives, becomes a devoted student utterly transfixed by the Christian ideal — “Master, according to the word of the Lord my God in the Holy Scriptures we are to admonish one another; there is no Greek, no Jew, no male, no female in Christ” — until she is drawn up short by the disparity between Christian promise and colonial norms.

Ester’s Uncle, now head of the extended family, is furious that his authority has been challenged:

“This girl is always trying to cause a problem, thinking she is too much betta than the others, YOU ARA NOT! And I say she must behave like a propa girl end do what she must be doing in our ways. I am saying, this girl is now mine.”

Esther’s aunt, who accuses her brother of arranging the marriage out of greed for the goats he’ll get as brideprice, accepts the good where she finds it. She dresses as Chilford’s housekeeper and recites his prayers by rote — “Hair Mary fur of Ghost” — but secretly tends the spirit world of her ancestors, central to Shona culture. (“It is our way, Masta, we must be treating the dead propery.”)

Ester’s volatile cousin Tamba, who happily defies his elders to help her escape a bad marriage, becomes alarmed by her rapid transformation as rebellion looms: “Now you are lost. Forgetting the ways of your peopo. Loving on the whites. What good ara they doing eh? Bringing this Jesas. You say he give and give till he die. What ara they giving eh? They ara teking end teking and you want to love them for that?”

Ester’s volatile cousin Tamba, who happily defies his elders to help her escape a bad marriage, becomes alarmed by her rapid transformation as rebellion looms: “Now you are lost. Forgetting the ways of your peopo. Loving on the whites. What good ara they doing eh? Bringing this Jesas. You say he give and give till he die. What ara they giving eh? They ara teking end teking and you want to love them for that?”

Gurira’s play resonates because she makes you care about them all. Their opposing points of view are entirely credible — even Chancellor at his drunken and deluded lowest and Uncle flailing dangerously under prideful siege. As history grinds relentlessly over them all, it’s the specific details of each one’s fate that draw our focus, while the big story arc sweeps up from below, like a musical score, and resonates long after.

Related Links:

- Zimbabwe history from pre-colonial times: Browse “Becoming Zimbabwe” by Brian Raftopoulos and Alois Mambo

- “The Convert” script is available for purchase at the participating theaters: Read an earlier version, not reflective of the latest changes, here

- Danai Gurira, actress: View her clips reel at danaigurira.com

- Three Chicago winners will converge upon New York City with finalists from other cities to compete in the final round of the August Wilson Monologue Competition May 7 at Broadway’s August Wilson Theatre: Playbill has the details — attendance is free

Photo captions and credits: The cast of “The Convert” is the same in all three premiere-sharing locations — the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton, N.J.; the Goodman Theatre in Chicago; and the Kirk Douglas Theatre (forthcoming) in Los Angeles. All production photos of “The Convert” are by T Charles Erickson.

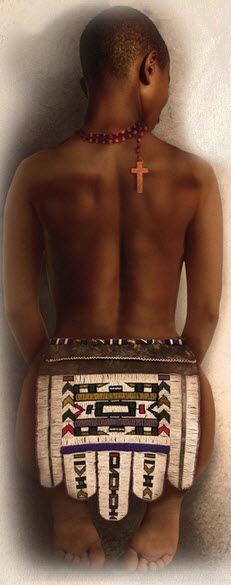

Home page and top: Playwright Danai Gurira flanked by two characters of her creation — the devout convert Ester (played by Pascale Armand) and her village cousin Tamba (Warner Joseph Miller.) Top left: Jekesai, before conversion to Esther. Top right: LeRoy McClain as Chilford, a well-educated African and would-be priest who takes Ester under his wing. AMC screen grab: Michonne, Gurira’s next role as actor, is a sword-wielding hero in “The Walking Dead” next season. Right of map: A Shona spiritual leader. (Hans Hillewaert, Wiki Commons)

Group scene left to right: Uncle (Harold Surratt) furiously demands the return of his niece, while Tamba and Chilford keep him well separated from Ester and her aunt Mai Tamba (Cheryl Lynn Bruce). Continuing down the page: Prudence (Zainab Jah) enjoys the good life of the black elite; Ester is studious and devout; Uncle insists he was robbed. Tamba and Mai Tamba (now stripped of her housekeeper uniform) feel the torment of no recourse.

Below: A map of the pioneer colonial routes to Salisbury. (Johan Steytler, US.archive.org)

Tags: British colonialism, Cheryl Lynn Bruce, Danai Gurira, Emily Mann, Goodman Theatre, Harold Surratt, Kevin Mambo, Kirk Douglas Theatre, LeRoy McClain, McCarther Theatre Centre, Pascale Armand, Pygmalion, Salisbury, Shona, Southern Rhodesia, The Convert, Warner Joseph Miller, Zainab Jah, Zimbabwe