‘Until the Flood’ at Goodman: A black youth falls to an officer’s gun; a community reflects

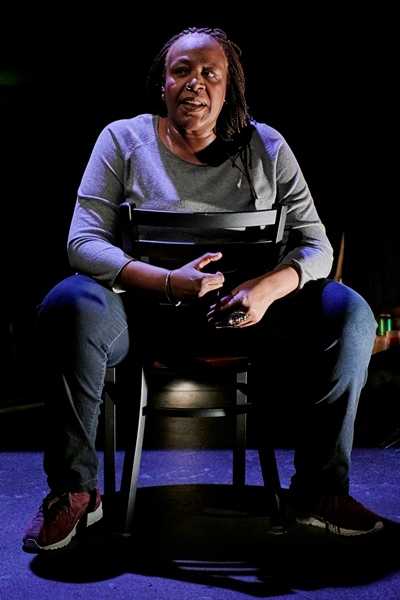

Review: “Until the Flood,” written and performed by Dael Orlandersmith, at Goodman Theatre through May 12. ★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

In the sense that we are all political creatures, with our personal agendas and blind spots and predispositions, Dael Orlandersmith’s one-woman play “Until the Flood,” now in a brief run at the Goodman Theatre, is thoroughly and unflinchingly a political work. It is a play about race and racism, but also about individual potential and personal accountability.

Specifically, “Until the Flood” is a multifaceted and remarkably evenhanded response to the fatal shooting of the African-American teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson the night of Aug. 9, 2014. The play was commissioned by the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis.

It is important to understand up front what Orlandersmith’s one-woman (but multi-character) narrative is not: It is not an indictment of any kind on any level. It is a distillation, or perhaps consolidation, of some 80 interviews this 45-year-old African-American woman conducted with white people as well as black. Orlandersmith’s deftly written and eloquently realized work speaks through personas black and white, in tones proud and daunted, conciliatory and defiant, and generally puzzled.

It is important to understand up front what Orlandersmith’s one-woman (but multi-character) narrative is not: It is not an indictment of any kind on any level. It is a distillation, or perhaps consolidation, of some 80 interviews this 45-year-old African-American woman conducted with white people as well as black. Orlandersmith’s deftly written and eloquently realized work speaks through personas black and white, in tones proud and daunted, conciliatory and defiant, and generally puzzled.

Rodney King’s still-resonant rhetorical question came to mind: “Can’t we all get along?” But that is not the cosmic mystery Orlandersmith explores here. “Until the Flood” seems to step back to a more fundamental conundrum that isn’t rhetorical at all: Why do we, white people and black people, not put down our shields of cultural isolation and our weapons of distrust? Why do we, generation upon generation, continue to heat our simmering animosity?

The embrace of Orlandersmith’s narrative begins with the unresolved matter of what really happened that August night in Ferguson. Did Michael Brown raise his hands and plead, “Don’t shoot”? Or did he make a full-on charge at a police officer who felt he had no choice but to react with lethal force? There is no answer to this one. Massive black protests ensued, but the fact remains that nobody knows. Orlandersmith’s characters – old and young, male and female, black and white, all portrayed by her – grapple with the question, and express some certainties that spin off that question.

A retired African-American high school English teacher laments that the young man would have started college in the fall. So what in the world was he thinking, she wonders, when he pocketed some cigars at a convenience store, the incident that got the police after him in the first place? Such a waste.

A retired African-American high school English teacher laments that the young man would have started college in the fall. So what in the world was he thinking, she wonders, when he pocketed some cigars at a convenience store, the incident that got the police after him in the first place? Such a waste.

Two black teen-age boys, one a happy-go-lucky street kid and the other a serious student hoping to study art history, see the world from Michael Brown’s point of view. The cool rapper says just being black seems to be reason enough for the cops to pounce; the young art buff cites his own instance, the time he got stopped for carrying an armload of books. Although so frightened he thought he would wet himself, he managed to convince the cop by pointing out that if he were to carry stolen goods in broad daylight, it wouldn’t be a tome on Michelangelo.

A black barber remembers the time, after the Michael Brown shooting, when two journalism students from Northwestern, a white girl and a black girl, came into his shop on a feature-writing expedition exuding sympathy for his lifetime of oppression. He didn’t know what they were talking about and made it clear that they didn’t, either. He’d built a very nice business for himself, and he didn’t need any liberal saviors to come rescue him.

Then there’s the thirtysomething white guy who has clawed out a good life on his own, including a college education, after escaping from an Appalachian boyhood of poverty and a drunken, abusive father. One day, he’d risen up and beaten his father with a chair, walked out of the house and never looked back. He owns several houses around St. Louis and rents to black people. They pay on time because they know they’d better. When he comes round, he comes packin’. He has no problem with black folks unless they bother him, unless they turn out to be That Word. Then he’d just as leave line ‘em up and shoot ‘em, all of ‘em.

Then there’s the thirtysomething white guy who has clawed out a good life on his own, including a college education, after escaping from an Appalachian boyhood of poverty and a drunken, abusive father. One day, he’d risen up and beaten his father with a chair, walked out of the house and never looked back. He owns several houses around St. Louis and rents to black people. They pay on time because they know they’d better. When he comes round, he comes packin’. He has no problem with black folks unless they bother him, unless they turn out to be That Word. Then he’d just as leave line ‘em up and shoot ‘em, all of ‘em.

That Word, that horrible word: No African-American will tolerate being called that name by a white person, observes one of Orlandersmith’s black characters, and yet blacks often apply it to each other in careless mutual degradation.

A white woman fondly remembers the now-retired black English teacher coming into her store. They knew each other by name. They would chat, the small talk of casual friends. The black teacher remembers those pleasantries, as well. And how after sundown, black folks had best be back in their own neighborhoods and off the streets – inside their homes, actually.

“Until the Flood,” directed by Neel Keller, is a photo gallery, snapshots from the streets and front porches and barbershops of Ferguson, Mo. No judgments are made; the images – the voices, the perspectives –are what they are. I loved the street-wise kid, exuberant in the fleeting immortality of youth, so full of himself, full of life. He knew Michael Brown, but just to say hey.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com