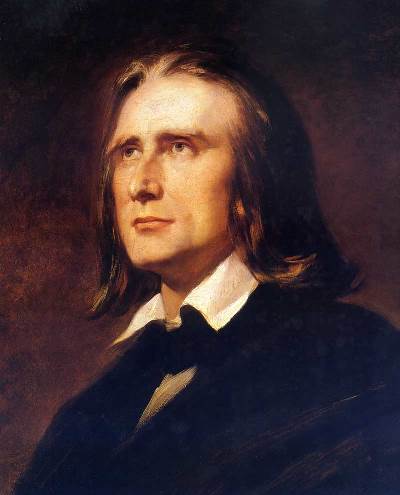

Pianist Emanuel Ax offers mosaics of Mozart and Beethoven, contrasts of Liszt and Bach

Review: Emanuel Ax, piano recital at Orchestra Hall on April 8.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Bookends of sorts embraced pianist Emanuel Ax’s imposing and indeed exhilarating recital April 8 at Orchestra Hall. That frame was made of Mozart and Beethoven, and its intriguing historical decoration consisted in how those composers shaped (or reshaped) two piano sonatas.

Mozart’s Sonata in F is attached to not one but two numbers in the Koechel catalog of his complete works. It is both K. 533 and K. 494, the latter referring to the splendid independent Rondo that Mozart repurposed as the third and final movement of the Sonata K. 533. Thus pieced together, it’s quite a formidable and magnificent piece, to which Ax brought equal parts of grace and clarity.

In the best classical Greek sense, Ax imbued the F major Sonata’s opening movement with a statuesque character of elegant proportion, line and expressive directness. This was crystalline playing, at once incisive and warm. The ensuing Andante is among Mozart’s most probing essays, deeply introspective and, in purely musical terms, fraught with bold harmonic explorations. All this Ax brought off with the essential further ingredient of an effortlessly singing line.

In the best classical Greek sense, Ax imbued the F major Sonata’s opening movement with a statuesque character of elegant proportion, line and expressive directness. This was crystalline playing, at once incisive and warm. The ensuing Andante is among Mozart’s most probing essays, deeply introspective and, in purely musical terms, fraught with bold harmonic explorations. All this Ax brought off with the essential further ingredient of an effortlessly singing line.

The final Rondo, which Mozart had composed for an exceptionally gifted student (the daughter of a benefactor), is one of those miracles of invention that, in hands such as Ax’s, never seem to lose their aura of spontaneity. It was a thoroughgoing delight, a wellspring of vivacity and witty surprise.

The Beethoven bookend, the sublime Sonata in C, Op. 53 (“Waldstein”) bespoke a historically opposite circumstance. Originally, Beethoven’s enduringly popular Andante favori in F was the middle movement of the “Waldstein,” until the composer (grudgingly) accepted the counsel of friends that the grandly wrought variations made the sonata too long. Beethoven replaced the Andante with a much shorter, ruminative, almost transitional middle movement – an effect he would return to with the slow movement of the Fourth Piano Concerto.

Ax prefaced the “Waldstein” with a sparkling turn through the movement eventually retitled Andante favori. His performance of the Sonata itself was a model of strength wedded to elegance, the opening movement closely focused and potent, the airborne finale a marvel of agility and technical finesse.

Between the historical charms of Mozart and Beethoven, Ax ventured into the full-blown Romanticism of Liszt and back to the contrapuntal wizardly of Bach. The first took the form of “Three Sonnets of Petrarch,” Liszt’s evocative and virtuosic distillations for piano of verses by the Italian Renaissance poet. Ax summoned an aura of expressive precision that verged on verbal, and in that churn of sound achieved emotional summits that reached their highest peak in the amorous despair of the second poem, “I find no peace, and know not how to make war.”

Between the historical charms of Mozart and Beethoven, Ax ventured into the full-blown Romanticism of Liszt and back to the contrapuntal wizardly of Bach. The first took the form of “Three Sonnets of Petrarch,” Liszt’s evocative and virtuosic distillations for piano of verses by the Italian Renaissance poet. Ax summoned an aura of expressive precision that verged on verbal, and in that churn of sound achieved emotional summits that reached their highest peak in the amorous despair of the second poem, “I find no peace, and know not how to make war.”

From worlds away came Bach’s Partita No. 5 in G, a suite of six dances introduced by a scintillating Praeambulum. If the technical mastery demanded by Liszt was overt to the point of overwhelming, the demands made by Bach’s keyboard music were electrifying in their brilliant delicacy. Ax gave stately aspect to the moderate Allemande, turned inward with the deliberate Sarabande and brought articulated power to the closing Gigue’s grand fugue. But in the effervescence of the speeding, highly ornamented Courante, I could feel the smile on my own face.

To all this, the perdurable pianist, who turns 69 in June, added two encores: a lyrical account of Chopin’s Nocturne in F-sharp, Op. 15, No. 2, and – with a deferential shrug when his listeners insisted – a fine-spun reading of Liszt’s “Valse oubliée,” No. 1.

Tags: Emanuel Ax