‘Mary Stuart’ at Chicago Shakespeare: Contest of queens for England’s throne is regal theater

“Mary Stuart” by Friedrich Schiller, translated by Peter Oswald, at Chicago Shakespeare Theater thru April 15. ★★★★★

By Lawrence B. Johnson

Everything about Friedrich Schiller’s battle-of-the-queens historical drama “Mary Stuart,” in its current staging at Chicago Shakespeare, proclaims compleat theater.

From Peter Oswald’s adroit translation of this German-language verse play to Jenn Thompson’s fluent direction and the masterful, knowing work of a large cast, CST’s “Mary Stuart” is a many-splendored triumph.

And no less credit is due, up front, to Andromache Chalfant’s imposing and adaptable sets as well as Linda Cho’s expressive period costumes and the lighting co-designed by Greg Hofmann and Philip Rosenberg. This show legitimately invokes Wagner’s term Gesamtkunstwerk – a fully integrated work of art.

And no less credit is due, up front, to Andromache Chalfant’s imposing and adaptable sets as well as Linda Cho’s expressive period costumes and the lighting co-designed by Greg Hofmann and Philip Rosenberg. This show legitimately invokes Wagner’s term Gesamtkunstwerk – a fully integrated work of art.

Written in 1800, Schiller’s play dramatizes, with effective license, the long-running contention between England’s Queen Elizabeth I and her cousin Mary, the deposed Queen of Scotland, for the right to the throne of England.

It is a one-sided battle: For many years, Mary Stuart has been imprisoned by Elizabeth while the English Queen agonizes over what to do about this pretender, a Catholic who represents a genuine threat to both the throne and the future of the Church of England. Elizabeth’s counsellors are divided on the question of whether Mary should simply be dispatched to the headsman or kept alive.

Though all the power rests with Elizabeth, in Schiller’s drama the Queen’s political savvy is matched by Mary’s righteous willfulness. Until near the end, the two women never even see each other, but carry on their bizarre struggle through intermediaries, amid intrigue and debate. The stand-off ends only when Elizabeth issues an ambiguous order for Mary’s death, and Mary’s supporters turn to desperate measures.

Though all the power rests with Elizabeth, in Schiller’s drama the Queen’s political savvy is matched by Mary’s righteous willfulness. Until near the end, the two women never even see each other, but carry on their bizarre struggle through intermediaries, amid intrigue and debate. The stand-off ends only when Elizabeth issues an ambiguous order for Mary’s death, and Mary’s supporters turn to desperate measures.

Chicago Shakespeare boasts a blazing pair of opponents in K.K. Moggie’s proud, headstrong, seductively beautiful Mary – an ungirdled force of nature — and Kellie Overbey’s somewhat older, wry and circumspect Elizabeth, who is at once a monarch unsure about her best course of action and a woman annoyed by the celebrated charms of her adversary. (The historical Elizabeth was nine years older than Mary, and that discrepancy in age is invoked perfectly here.)

While Moggie’s estranged Mary rants against her circumstances and the slights of her oppressors, vowing that she will prevail in what is rightfully hers, the crown of England, the woman who wears that crown sorts through the urgent remedies pressed by her courtiers – with the odd aside to rebuff yet another envoy from the court of France seeking to bind the two counties through marriage.

What both voices share, in their disparate temperaments, is clear, expressive language, a virtue that resonates across this cast. These are disciplined, probing actors who show their respect for and comprehension of the words they’re speaking. Oswald’s translation, though modernized, unfolds in richly layered English with a distinctive pulse that drives the text forward.

What both voices share, in their disparate temperaments, is clear, expressive language, a virtue that resonates across this cast. These are disciplined, probing actors who show their respect for and comprehension of the words they’re speaking. Oswald’s translation, though modernized, unfolds in richly layered English with a distinctive pulse that drives the text forward.

When the rival queens finally meet, it is just outside Mary’s prison walls where she, unaware of the setup, savors an unexpected hour of liberty, frolicking in a shallow pool and laughing with her old nurse (the heatedly eloquent Barbara Robertson). This will be Mary’s chance to show Elizabeth some conciliation, some deference, and perhaps even gain her freedom.

Not likely. In Mary’s almost immediate, explosive burst of indignation – and Moggie is fierce – one could only think of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, that imperious general who goes before the people to seek their endorsement, hat uneasily in hand. Like Schiller’s contemptuous queen, he quickly turns his scorn upon them. Where Coriolanus might kick dirt on the plebs who would approve him, Mary splashes water on the woman empowered to decide her fate.

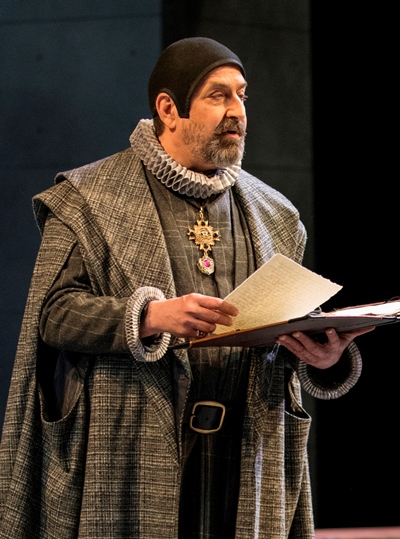

Vivid characters populate CST’s stage. Just as Mary in her isolation enjoys the passionate moral support of Robertson’s nurse, Elizabeth is surrounded by courtiers of engaging depth and individuality. As Lord Burleigh, the Queen’s treasurer and ardent voice against Mary, David Studwell embodies firm resistance to both “the Stuart” and resurgent Catholicism.

Vivid characters populate CST’s stage. Just as Mary in her isolation enjoys the passionate moral support of Robertson’s nurse, Elizabeth is surrounded by courtiers of engaging depth and individuality. As Lord Burleigh, the Queen’s treasurer and ardent voice against Mary, David Studwell embodies firm resistance to both “the Stuart” and resurgent Catholicism.

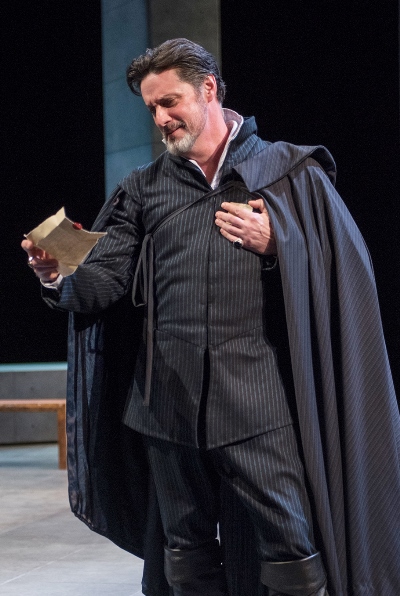

Tim Decker brings a brazen confidence to Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth’s longtime favorite – and lover. Among the play’s more remarkable patches is Leicester’s unabashed lie when he’s confronted by transparent evidence of his collusion with Mary. He would be right at home in modern politics. Decker fashions Leicester’s bald-faced spin with hilarious cheek.

In an affectingly understated performance, Robert Jason Jackson blends earnest mind and weary body in old George Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsberry, adviser to Elizabeth but also compassionate advocate for Mary. Kevin Gudahl is a picture of moral rectitude as the knight in charge of Mary’s imprisonment, just as Andrew Chown captures all the impetuosity of the smitten young Mortimer, a converted Catholic who risks – and loses – everything in a mad scheme to free the comely Queen of Scots.

Chicago Shakespeare’s “Mary Stuart” – ambitious, concentrated, handsome and smart – is the sort of grand production that defines the company. It is a theatrical masterpiece not to be missed.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com

Tags: Andrew Chown, Andromache Chalfant, Barbara Robertson, Chicago Shakespeare Theater, David Studwell, Friedrich Schiller, Greg Hofmann, Jenn Thompson, K.K. Moggie, Kellie Overbey, Kevin Gudahl, Linda Cho, Mary Stuart, Peter Oswald, Philip Rosenberg, Robert Jason Jackson, Tim Decker

1 Pingbacks »