Young maestro walks into house Reiner built, confronts CSO and a daunting Strauss legacy

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada; Baiba Skride, violin. At Orchestra Hall thru Oct. 30.

By Nancy Malitz

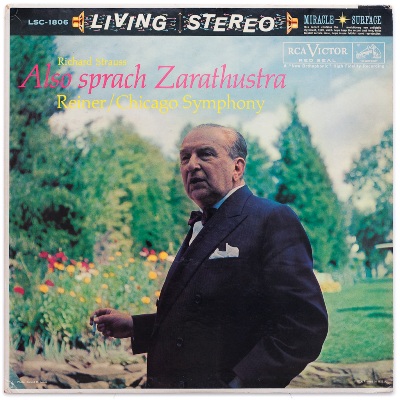

Among the works embedded in the living DNA of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is surely Richard Strauss’ “Also sprach Zarathustra,” recorded in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall at the dawn of the stereo era, in 1954, led by the great Hungarian conductor Fritz Reiner at the height of his powers, music director of the CSO and also Strauss’ dear friend.

Although the musicians in Reiner’s band are mostly a memory now, the 1958 RCA Living Stereo recording of that event is – I’m as sure as I can be – intensely alive still in the heart of every Chicago Symphony musician and classical record enthusiast. If you have only a dozen recordings in your collection, this is going to be one of them. (In the similarly coveted CD reissue, “Zarathustra” is paired with Strauss’ “Ein Heldenleben.”)

Although the musicians in Reiner’s band are mostly a memory now, the 1958 RCA Living Stereo recording of that event is – I’m as sure as I can be – intensely alive still in the heart of every Chicago Symphony musician and classical record enthusiast. If you have only a dozen recordings in your collection, this is going to be one of them. (In the similarly coveted CD reissue, “Zarathustra” is paired with Strauss’ “Ein Heldenleben.”)

Featuring a nattily attired Reiner photographed in a three-quarter profile, sporting a bow-tie and breast-pocket kerchief, a cigarette dangling stylishly between his fat thumb and fore-fingers, a garden of glorious green and colorful flowers behind, this CSO “Zarathustra” captures not only the sonic equivalent of the thrill of sunrise, but the ascendancy of the Chicago Symphony and America itself in a rapidly evolving postwar culture. Far from delivering only bone-rattling sensations, the mid-20th-century recording is an exquisitely beautiful musical journey, a cultural touchstone.

And so it must be with a certain prideful reluctance that the musicians of the Chicago Symphony face each new generation of conductors eager to take their own shot with the CSO at this work central to the canon. I caught up with the second night in a three-concert run featuring the debut of 38-year-old Colombian conductor Andrés Orozco-Estrada, who did not score a clear success with “Zarathustra.”

Strauss’ musical transmogrification of Nietzsche’s epic prose-poem was the anchoring work on the concert’s second half, preceded by Ives’ six-minute mystery, “The Unanswered Question,” which comes and goes in a whisper. Orozco-Estrada paired them so that the Ives flowed directly into the Strauss, as if “Zarathustra” might in fact be some kind of an answer to the existential ripple in eternity that is suggested by Ives’ music.

My reaction was that using three trumpets in remote acoustical hideaways for the Ives was a nifty idea. Give Orozco-Estrada credit for that. His other idea – to flow Ives and Strauss together – might win him an A for clever thinking in a graduate essay, and it’s indeed fun to think of rolling the argument around in a late night conversation. But the effect in concert was to rob the Strauss of its own miraculous impact – that sense of something emerging from absolutely nothing in those first few seconds. Instead, we got “Previously, on ’24.'”

My reaction was that using three trumpets in remote acoustical hideaways for the Ives was a nifty idea. Give Orozco-Estrada credit for that. His other idea – to flow Ives and Strauss together – might win him an A for clever thinking in a graduate essay, and it’s indeed fun to think of rolling the argument around in a late night conversation. But the effect in concert was to rob the Strauss of its own miraculous impact – that sense of something emerging from absolutely nothing in those first few seconds. Instead, we got “Previously, on ’24.'”

Highly energetic on the podium, Orozco-Estrada put a lot of bounce and body language into every single beat. Each orchestra is different, but the result in the case of Chicago Symphony musicians was not so much to pump up the energy as to diminish the expressive range. There was simply too much beat-heavy, over-the-top loudness and not enough of a complex picture incorporating linear direction and dramatic detail. Perhaps Orozco-Estrada sensed something lacking, too, and tried to compensate by revving things up even more. But the interaction seemed awkward, as with acquaintances not yet friends.

Kodály’s “Dances of Galánta,” with which the concert began, was the most successful effort of the evening. In fact, it was a fairly auspicious beginning for the conductor, characterized by a certain urbane elegance. But then came another debut, that of 35-year-old Latvian violinist Baiba Skride, in the Sibelius Violin Concerto, an interaction that also seemed awkward and perplexing.

Kodály’s “Dances of Galánta,” with which the concert began, was the most successful effort of the evening. In fact, it was a fairly auspicious beginning for the conductor, characterized by a certain urbane elegance. But then came another debut, that of 35-year-old Latvian violinist Baiba Skride, in the Sibelius Violin Concerto, an interaction that also seemed awkward and perplexing.

I heard this same violinist perform the equally demanding Bartok Second Violin Concerto last February with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Christoph Eschenbach, and it was a resounding success. Skride has plenty of muscle, but she is also given to daring attempts at dramatic inflection via silky, gossamer – even icy – effects at the extreme soft end of the palette, and these passages did not come off successfully in the Sibelius I heard in Chicago.

A matter of balance, perhaps. She was best in the dark, throaty Adagio. But the big and fast stuff didn’t really seem to work consistently for her, either, and the orchestra was at times overpowering. One could chalk this night up to a mismatch of temperaments all around, but that’s probably too easy. More likely, we were witnessing the necessary tempering that hard experience brings to all performers.

Related Links:

- Chicago Symphony concert calendar: Visit CSO.org

- Highlights of the CSO’s 2016-17 season: Check out this overview

Tags: Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Baiba Skride, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Fritz Reiner