Famous trouser roles folded away, opera star von Stade channels a queen of Egypt (Texas)

Interview: Still learning new roles in semi-retirement, mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade analyzes the steel-under-silk persona of Myrtle Bledsoe in “A Coffin in Egypt,” now playing at Chicago Opera Theater through May 3.

By Nancy Malitz

Frederica von Stade broke through to opera fame for her boisterous interpretations of the “trouser” roles that showcase young mezzo-sopranos. With her slim physique and impish wit, the beloved American-born opera singer had no trouble impersonating the adolescent pageboy Cherubino, one of Mozart’s most charming characters, an adoring servant with sex on the brain who amuses his Countess — and enrages the Count — in “The Marriage of Figaro.”

Von Stade’s Cherubino was a signature role that made her famous in the early 1970s. And although she hasn’t done the role in decades, the interpretation is so spot-on that it’s eternal in the viral video realm.Eventually, von Stade would tear up new turf in other genres, and she’s still doing that in semi-retirement. She turns 70 on June 1.

Her latest specialty is the willful woman of a certain age whose imperfect life is prime for the telling. Feisty divas, mothers, dowagers and grande dames have proved irresistible to von Stade when she is petitioned by loyal composers and their collaborators to enact them.

“I am at the stage where I say that if they think I can do the role, then I think I can do the role, and what have I got to lose?” von Stade said of this new chapter. So it’s out with the light-hearted Mozart and Rossini comedies, and in with some vintage women who have axes to grind.

“I am at the stage where I say that if they think I can do the role, then I think I can do the role, and what have I got to lose?” von Stade said of this new chapter. So it’s out with the light-hearted Mozart and Rossini comedies, and in with some vintage women who have axes to grind.

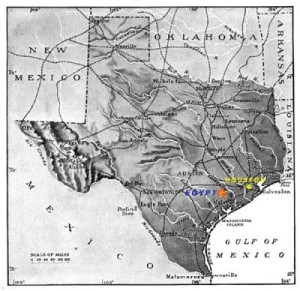

At Chicago Opera Theater von Stade is revisiting the 2014 role she created in “A Coffin in Egypt,” which she did first in Houston, then Philadelphia and Los Angeles — the project of composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettist-director Leonard Foglia, based on an original play by Horton Foote. It’s essentially a monodrama for her with a quartet of supporting singers, a few spoken roles and a small chamber orchestra. Von Stade carries the dramatic load as Myrtle Bledsoe, the fiercely complicated 90-year-old widow of a philandering rancher baron from Egypt, Tex.

Her husband’s outrages were many and Myrtle’s memories are vivid, if faltering, of her long life of stultifying entrapment, marked some pretty exotic and far-flung countermeasures — for a woman in her day, anyway. She actually took her kids and fled to Europe, where she stayed for seven years before returning to her Egypt domicile.

Myrtle shares something of the toughness of spirit that marks Stephen Sondheim’s fictional Carlotta in “Follies”: “Good times and bum times, I’ve seen ‘em all/And, my dear, I’m still here.” But Myrtle is of an earlier generation. Women didn’t leave marriages then. And Myrtle is modeled after a legend who actually lived.

Myrtle shares something of the toughness of spirit that marks Stephen Sondheim’s fictional Carlotta in “Follies”: “Good times and bum times, I’ve seen ‘em all/And, my dear, I’m still here.” But Myrtle is of an earlier generation. Women didn’t leave marriages then. And Myrtle is modeled after a legend who actually lived.

“That’s what been so much fun to do this, because my character was a real woman,” said von Stade as she relaxed in her Chicago flat shortly before the Chicago Opera Theater opening. “She was actually called ‘the Queen of Egypt.’ I went to Egypt, Texas, to learn about her – and it is just a crossroad. Most of these little Texas towns, you come into them and they are very derelict, just cheap motels and trucks until you get to the center square, where there’s usually a courthouse surrounded by little shops, and then it becomes very quaint. The country around is vast and beautiful, however. You’re driving and, all of a sudden, Houston just stops and there are open fields in all directions.”

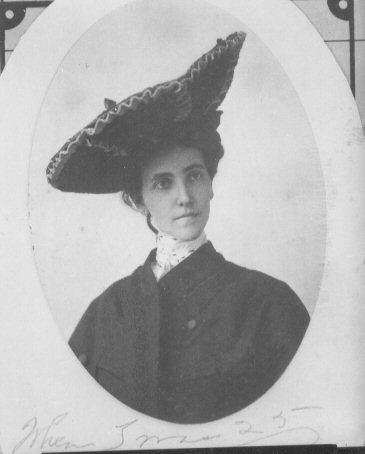

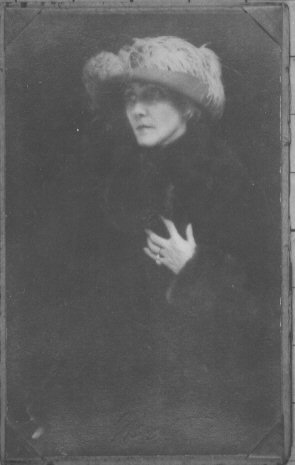

“A Coffin in Egypt” is an imagined portrait drawn from the life of Clarissa Beard Northington, the wife of a wealthy Wharton County farmer and horse breeder who was the son of one of Texas’ oldest families. The people of Wharton County inspired many plays by Horton Foote, who died in 2009 and is often referred to in theater circles as “the American Chekhov.” Foote is perhaps most widely known for the films “A Trip to Bountiful” and “Tender Mercies,” and for his cinematic adaptation of “To Kill A Mockingbird.”

“A Coffin in Egypt” is an imagined portrait drawn from the life of Clarissa Beard Northington, the wife of a wealthy Wharton County farmer and horse breeder who was the son of one of Texas’ oldest families. The people of Wharton County inspired many plays by Horton Foote, who died in 2009 and is often referred to in theater circles as “the American Chekhov.” Foote is perhaps most widely known for the films “A Trip to Bountiful” and “Tender Mercies,” and for his cinematic adaptation of “To Kill A Mockingbird.”

“What Horton Foote has done with ‘A Coffin in Egypt’ is very truthful, according to people that actually knew the character I’m creating,” von Stade said. “After reading the stage play, I wondered why it wasn’t being performed, and I learned it was in his wishes that it not be done until he was gone, because it tells the truth about a lot of people.” (The show’s low profile did include a brief run in 1998, during a New York summer in Sag Harbor, starring Glynis Johns.)

“But it’s not an unkind truth, the way he writes it,” von Stade said. “It’s like a gentle flow, very descriptive, with a deep sense of appreciation of who these people are in telling the truth about them. When I was there, I met one lady who said her grandmother went with Clarissa on part of the trip when at one point she left with her kids to Europe because her husband was so mean. And when we took the show there, concert style, to this teeny old movie theater in (nearby) Wharton that seats about 200 people, at the end of it a gentleman stood up and said that after seeing this and hearing this he wished he had known his aunt better.

“I also met a rancher, kind of my age, maybe a little younger, who said, ‘You know, I could kick myself, because I was just so wanting to get over to her house to interview her and put a lot of pictures together, so that who she was wouldn’t get lost, but I didn’t get to it. I got too busy.’ Of course we’re talking about a rancher who had thousands of acres to take care of.”

“I also met a rancher, kind of my age, maybe a little younger, who said, ‘You know, I could kick myself, because I was just so wanting to get over to her house to interview her and put a lot of pictures together, so that who she was wouldn’t get lost, but I didn’t get to it. I got too busy.’ Of course we’re talking about a rancher who had thousands of acres to take care of.”

Von Stade came to understand Foote’s hesitation about telling Myrtle’s story, which involves murder, child abuse, interracial scandal and even resentment from her daughters, who blamed her for their father’s straying. “There was very little that a woman of that time could do in her situation, especially if she had children,” von Stade said. “She had to go back. I’m sure that’s why she didn’t stay in Europe, for the sake of the children, their future and their reputations.”

Back in Egypt, Clarissa remained married, wrote and published poetry, painted watercolors of the flowers in her landscape and entertained artists who visited from around the world. She died in 1979, one month shy of 100 years old. But von Stade said it’s clear there is a mutual anger between the generations and hostility still.

“At one point I asked about contacting my character’s granddaughter, who is alive in her 90s, just to say what a privilege it has been to get to know her family through all this. And we got a message back that said, ‘If I saw Horton Foote, I’d blow his brains out!‘”

Next season, von Stade will create yet another new female powerhouse. She’s booked for the world premiere of “Great Scott” with the Dallas Opera, as “Winnie” Flato, the founder and chief benefactor of a struggling opera company. (Think Bernadette Peters in “Mozart in the Jungle.”) As Winnie’s company sails toward opening night of a long-lost opera discovered by the international opera star who will perform it, her husband’s national football franchise streams toward its first-ever national championship on the same night. It’s the project of composer Jake Heggie and playwright Terrence McNally. “Great Scott” also will spotlight mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato as the international singer who is championing the forgotten lyric gem, thus pairing two all-time fan favorites from successive generations.