Van Zweden, CSO plumb Shostakovich Seventh to kick off festival on theme of ‘Truth to Power’

Feature review: Music of Prokofiev and Britten also on docket for 18-day exploration of works created during World War II, through June 8.

Feature review: Music of Prokofiev and Britten also on docket for 18-day exploration of works created during World War II, through June 8.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

With a ringing affirmation of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, conductor Jaap van Zweden and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra have plunged into a multifaceted festival celebrating three great 20th-century composers whose music sprang from personal and political tumult.

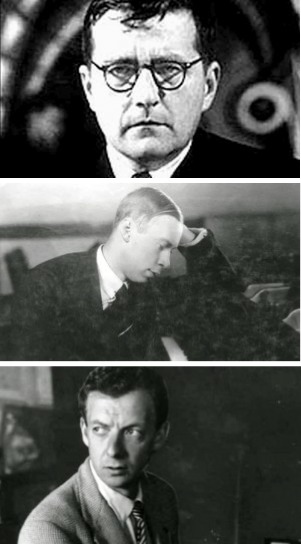

In all, the festival, dubbed “Truth to Power” and devoted to music of Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev and Benjamin Britten, features 14 performances of seven different concert programs across 18 days, with another 11 lectures and presentations designed to provide cultural perspective on the Cold War, the film score activity that characterized all three, and the effects of war and political oppression on poets in both England and the Soviet Union.

In the days leading up to the festival, van Zweden spoke by telephone about the works he had selected, including the Shostakovich Seventh Symphony, which he felt was “strongly influenced by the chaos and destruction of World War II. It is a huge scream again fascism – though not so literal as the Eighth Symphony, where you hear the bombs falling.”

If the sweeping, 80-minute Seventh Symphony doesn’t evoke bombs, it surely summons the fearsome specter of Hitler’s invading army. Written as the German siege cannons were pummeling Leningrad, where Shostakovich did double service as composer and member of the fire brigade, the Seventh’s narrative arc extends from a time of peace in the motherland to the inexorable march of German boots through soul-searching and hope to the final imagined triumph of a population half-starved, tattered and delirious.

Van Zweden made a powerful case Friday night for a work that from the start has perplexed and put off many Western listener. Bartok in his Concerto for Orchestra famously parodied the prodigiously repeated march tune that forms the core of the Seventh’s vast opening movement. But in van Zweden’s hands, the experience was not one of mere repetition but rather of rising terror. By skillful degrees, Van Zweden built up the aural image of a force almost beyond resistance. And the CSO — its bolstered forces now including nine French horns and half dozen each of trumpets and trombones — drove it home with no less precision than clamor.

Yet the heart of the Seventh Symphony lies in its epic third movement, a sprawling canvas upon which Shostakovich depicted the suffering and the quiet resolve he must have witnessed all around him. It is music of sublime lyricism, reflective and painful, profoundly humane. Here was the Chicago Symphony at its virtuosic and elegant best, under the guidance of a conductor who manifestly had this music no less in his heart than in this head. The effect on the audience was plain enough, in a ripping ovation that belied the emotional drain of an intense hour and 20 minutes.

The Seventh is one of three Shostakovich symphonies that van Zweden will present with the CSO during the festival, which extends to June 8. Like Shostakovich, Britten and Prokofiev were active during the World War II years and its aftermath and were subjected to various social and political pressures even as they continued to create.

“Shostakovich, Britten and Prokofiev are connected by the trials they endured, and in their darkest moments they all produced the most amazing music,” van Zweden said. Beyond the stresses of the war itself, van Zweden noted various “difficulties in their personal lives – Prokofiev with homesickness, Britten in his struggles with being gay, Shostakovich always being pushed down by the Soviet regime.

“The stifling of all three of the composers is there, obviously,” he said. “Yet still, what came out musically is just amazing. I sometimes have the feeling that by writing this music it heals them. I can visually almost feel it when I look at such beautiful ideas on the paper. It is healing without medicine, through expression, to put your talent on the paper like this. A catharsis.”

Van Zweden’s assemblage of programs includes major works such as Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concerto with solo cello, often called the Sinfonia Concertante, that Mstislav Rostropovich — a friend to all three composers — championed. Alisa Weilerstein will play it May 29-30. Van Zweden described it as an “uncharacteristically dark piece, but also a masterwork, filled with beautiful melodies and splendid skill. Although the orchestra is huge, it is transparent. The cello is always heard and the colors are unbelievably rich.”

Among Britten’s works, Van Zweden singled out the Sinfonia da Requiem, planned for May 31-June 1. “It’s Britten’s most important symphonic work,” he said. “It moves me as a very personal statement by a composer deeply opposed to war.”

To round out the festival June 5-8, van Zweden chose Shostakovich’s popular Fifth Symphony over the Fourth — which was half completed, with Stalin’s reign of terror underway, when the composer was officially denounced for writing “muddle instead of music” and had good reason to fear for his life. On May 31 and June 1, van Zweden will introduce the little known and rarely performed “Five Fragments,” which were written while Shostakovich was planning the Fourth, and are reflective of his compositional language and tone in those years. Stalin’s Great Purge lasted from 1934-1940.

The Fifth was first performed in 1937, at the height of the terror, when during the course of a single year half a million people were shot and seven million sent to slave labor in the Gulag — poets, artists and leaders of the Russian intelligentsia notable among them. Compared to the Fourth, the Fifth Symphony displays a significantly simpler and more tuneful style, heroically, even if darkly, triumphant. It was not only instantly popular but also won Shostakovich temporary redemption with the regime. In part for that reason, Cold War music historians and performers have long debated the work, some arguing that Shostakovich had crumbled under the yoke to write falsely patriotic and joyful music, others insisting that it spoke with the height of irony, its parodoxes intended as secret code.

The Fifth was first performed in 1937, at the height of the terror, when during the course of a single year half a million people were shot and seven million sent to slave labor in the Gulag — poets, artists and leaders of the Russian intelligentsia notable among them. Compared to the Fourth, the Fifth Symphony displays a significantly simpler and more tuneful style, heroically, even if darkly, triumphant. It was not only instantly popular but also won Shostakovich temporary redemption with the regime. In part for that reason, Cold War music historians and performers have long debated the work, some arguing that Shostakovich had crumbled under the yoke to write falsely patriotic and joyful music, others insisting that it spoke with the height of irony, its parodoxes intended as secret code.

With the relaxing of the Iron Curtain, and the availability of more historical material, Shostakovich’s behavior has come to be viewed more widely by scholars as consistent with the strategic retreats and stylistic parries of his surviving cultural class. For his part, van Zweden said he hears distinct irony in the music of the Fifth itself: “The thing about the finale is that it seems like victory, but I think it is actually the opposite. I think he is actually screaming there.”

Van Zweden also chose the exuberant and mordantly witty Ninth — which was largely written after May 1945, the war’s end — over the far from optimistic Eighth, from 1943, with the war still raging. The wild and complex Eighth was initially supported by the regime and later banned from 1948-56. Van Zweden said he wanted to program the Eighth for this festival, but the work was already inked in for next season, with Semyon Bychkov conducting.

With a view to putting together a balanced festival program, Van Zweden said he did not want only dark works in any case: “The Ninth Symphony is also ironic, although in a completely different way. The government was expecting him to write his Ninth like Beethoven’s Ninth, a devastating Ninth, yet he came up with something that seems very happy in the context of his composing style. It is very light, as if he were saying, ‘Don’t expect me to think that just because this is my Ninth, it is my last.’ ”

Related Link:

- Progamming, dates and times for the “Truth to Power” festival: Details at CSO.org

Tags: Alisa Weilerstein, Benjamin Britten, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Dmitri Shostakovich, Jaap van Zweden, Sergei Prokofiev

No Comment »

2 Pingbacks »

[…] [Editor’s note: Van Zweden had a leading role in the Chicago Symphony’s 2014 festival “Truth to Power.&#…] […]