Pianist Kirill Gerstein lavishes virtuosity and wit on a glittering Prokofiev concerto with the CSO

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Semyon Bychkov; Kirill Gerstein, piano. At Orchestra Hall through Oct. 26.

Review: Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Semyon Bychkov; Kirill Gerstein, piano. At Orchestra Hall through Oct. 26.

By Lawrence B. Johnson

This weekend’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra program is a curiously mixed affair. At intermission, I was exhilarated at having witnessed Kirill Gerstein’s virtuosic and sly performance of Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2. On the other hand, by the time conductor Semyon Bychkov had made it to the end of a solidly fashioned performance of William Walton’s sturdily made Symphony No. 1, I was wondering why, some 80 years along, are American orchestras still dusting this off?

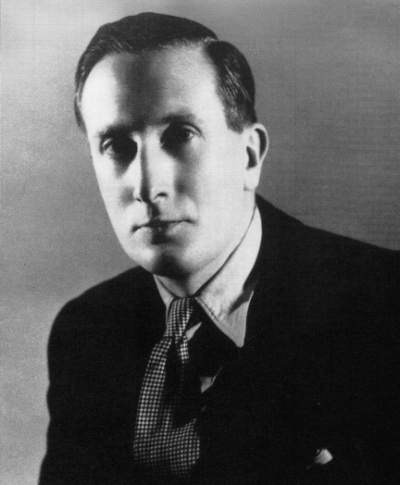

Gerstein, 34, a Russian-born American and winner of the 2010 Gilmore Artist Award, flashed his technical wizardry in a display that reminded one of what a demonic pianist the composer must have been.

Gerstein, 34, a Russian-born American and winner of the 2010 Gilmore Artist Award, flashed his technical wizardry in a display that reminded one of what a demonic pianist the composer must have been.

The original version of this knuckle-breaking work, written about the time of Stravinsky’s “Le sacre du printemps” when Prokofiev was in his early twenties, was lost when he left Russia for a visit to the U.S. in 1918. With the Third Piano Concerto already behind him – Prokofiev played its world premiere with the CSO under Frederick Stock in 1921 — he proceeded to reconstruct the four-movement Second from memory.

Not surprisingly, what resulted melds the unabashed bravura of the younger composer with the stylistic elegance, and indeed rhetorical touches, of the Third Concerto.

From the outset, Prokofiev’s Second Concerto bespeaks a pianist-composer bent on reshaping the concerto form to his purpose. The classical dialogue between keyboard and orchestra goes out the window almost immediately, as the pianist launches into a prodigious solo too long even to be characterized as a soliloquy. Something closer to an improvised rhapsody, perhaps.

As Gerstein, in the guise of Prokofiev, rippled through the glittering twists and ruminative excursions of this unfolding episode, one had a sense of a virtuoso unbound. Playing with off-hand brilliance and innate drollery, Gerstein seemed the consummate musician, lost to the world.

As Gerstein, in the guise of Prokofiev, rippled through the glittering twists and ruminative excursions of this unfolding episode, one had a sense of a virtuoso unbound. Playing with off-hand brilliance and innate drollery, Gerstein seemed the consummate musician, lost to the world.

The concerto’s three remaining movements cast pianist and orchestra in a more conventional relationship, though Prokofiev’s writing for both bears his own quirky stamp – the pianistic wit, the incisive incursions of woodwinds, the silken string sound that bundles all the other voices together. In the finale, Gerstein unleashed a sparkling torrent of sound deftly accented at every turn by Bychkov and an orchestral ensemble alert not just to timing but also to expressive point.

How paradoxical that Prokofiev’s piquant music was produced a full decade – two, actually – before Walton’s restrained and circumspectly correct First Symphony. It bears noting that the Chicago Symphony had last performed the work 35 years ago, under the baton of Charles Mackerras. Nor is Bychkov the only living conductor who revisits the First Symphony. It’s an attractive work, skillfully crafted from inviting thematic ideas.

How paradoxical that Prokofiev’s piquant music was produced a full decade – two, actually – before Walton’s restrained and circumspectly correct First Symphony. It bears noting that the Chicago Symphony had last performed the work 35 years ago, under the baton of Charles Mackerras. Nor is Bychkov the only living conductor who revisits the First Symphony. It’s an attractive work, skillfully crafted from inviting thematic ideas.

But it also strikes me as a work of, and limited by, its time. The First Symphony has been likened to the music of Sibelius: Some rhythmic and structural similarities are notable and creditably subsumed within Walton’s own language. What is not there is Sibelius’ keen sense of tension. And the work’s last flourish, a series of egregiously spaced exclamation marks, seem rather like a send-up of the Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony.

The really telling comparison is with Shostakovich, whose similarly grand symphonies sustain their place in the repertoire, arguably because they still speak to us through their modernist commingling of tumult and pathos. The Walton First Symphony is too comfortable, like an overstuffed armchair. At its most fraught, it brings to mind the composer’s vivid cinematic scores for Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare films. But the symphony never quite evokes its own internal drama.

The really telling comparison is with Shostakovich, whose similarly grand symphonies sustain their place in the repertoire, arguably because they still speak to us through their modernist commingling of tumult and pathos. The Walton First Symphony is too comfortable, like an overstuffed armchair. At its most fraught, it brings to mind the composer’s vivid cinematic scores for Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare films. But the symphony never quite evokes its own internal drama.

Still, credit Bychkov with a sympathetic, indulgent account and the CSO with a worthily opulent performance. In the programing cycle, the Walton First should next show up around 2048. And not before.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at CSO.org

- Prokofiev as Russian revolutionary: Read the essay here

- A William Walton profile: Read it here

Tags: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Kirill Gerstein, Semyon Bychkov, Sergei Prokofiev, William Walton