Diverse styles on display in MusicNOW series reflect rich, complex cultural stew of Chicago

Composer-violinist Curtis Stewart and Chicago Symphony resident composer Jessie Montgomery chat about their new works for MusicNOW at Orchestra Hall. (Todd Rosenberg photos)

Commentary: The bargain concerts curated by Chicago Symphony resident composer Jessie Montgomery are topped off by free pizza.

By Nancy Malitz

At yet another of its fascinating new-music concerts this season, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s MusicNOW event on March 3 ‒ conceived by the orchestra’s composer-in-residence Jessie Montgomery ‒ put me in mind, improbably enough, of Mozart.

From early youth, Mozart’s music overflowed with the influences of all he experienced in his travels through the cosmopolitan centers of Paris, Rome, Venice, Mannheim, London, and Vienna. If descended from the silver-plated melting pots of Old World empires, American classical music today is a unique cultural stew of its own, richly influenced by ethnic mixes of New York City’s Lower East Side, where Montgomery grew up, and of similar neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles, San Francisco, Dallas and Detroit.

Chicago is, absolutely, such an invigorating place to be. Emerging artists of all kinds are influenced not only by what they discover in the city’s museums, theaters, concert halls and jazz clubs, but also by the sights and sounds in gathering spots of the Central Loop and ethnic neighborhoods. Given the music anchoring street corners and weekend fairs, the contemporary smorgasbord of food, the aggressive architectural stew of buildings around us, and the parades of all nationalities in the summer streets, the Windy City’s array of international influences is comparable to that of a monarchy’s cosmopolitan reach in Mozart’s day.

Conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya led selected Chicago Symphony musicians and guest artists in six new works, including two world premieres, at Orchestra Hall.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s MusicNOW concert at Orchestra Hall on March 3, curated by Montgomery, included a world premiere of her own Concerto Grosso with solo violin, and part of a new violin concerto by Curtis Stewart called “Resonance,” still in the midst of creation. Lidiya Yankovskaya conducted. The event warmed up with an older piece by Cuban-American composer Tania León, “Arenas d’un Tiempo” (The Sands of a Time), from 1992.

León’s title summed up the nature of the weekend matinee for me. Rich in music inspired by memory and generations passing, the concert was attended by a large number of local composers, many young ‒ certainly not only those who label their music as “classical.”

Indeed, Montgomery’s MusicNOW programs attract listeners of all ages, judging from the occasional six- or seven-year olds in the great swath of twenty-somethings I saw on the main floor. And why not? The four-concert season package, at $90, is comparable to four movie tickets at the AMC. And unlike cinema food prices, the concert’s after-party pizza in the rotunda is free.

The four-time nominated Grammy composer Curtis Stewart had an upbringing not unlike Montgomery’s. Both are artists influenced by parents who were at the cutting edge in their own musical and theatrical fields, and both are responsive to the international ethnic stew of their upbringing.

Montgomery was born to jazz saxophonist Ed Montgomery and Broadway actress Robbie McCauley, who was also a playwright. Stewart, who is a professor at Juilliard and artistic director of the American Composers Orchestra, was born to a Greek-American mother (Elektra Kurtis-Stewart) who was a composer-violinist, and a jazz tuba player (Bob Stewart) who toured and recorded with Charles Mingus, Muhal Richard Abrams and Dizzy Gillespie.

It is not at all unusual for American classical music today to stem from roots like these, although it still causes the occasional contemporary kerfuffle about just what the definition of “classical music” really should be. That’s a lively conversation that is, and should be, ongoing.

The MusicNOW concert opened with the short piece “Arenas d’un Tiempo” (The Sands of a Time), the subtly shifting memory play composed in 1992 by the legendary Cuban-American Tania León. It was by far the oldest work on the program.

Now 80, the remarkable León never misses a chance to pay homage to her father by relating the advice he gave her as a young adult, when she came home to Cuba for a visit from her new home in New York City. Already an emerging composer then, Tania played one of her pieces for her dad, who responded that it sounded nice, but that he couldn’t hear “her” in her music. It’s one of those fundamental life lessons ‒ balm to the soul for any creative youth needing a nudge to express his or her unique self. The message also set the tone for the MusiNOW event, which seemed foremost about paying homage to the nurturers who set us free.

Of the two world premieres, Montgomery’s is a genial two-movement Concerto Grosso that featured the visiting violinist-composer Stewart as soloist. Stewart, like Montgomery, is both a classically trained composer with impressive bona fides and an ace violinist, intensely communicative, with a gift for making things up on the fly in the spontaneous tradition of jazz. Montgomery’s concerto seemed for him almost custom-made, in that it contains written-out solo passages but also offers the option for the violinist to indulge his own flourishes instead. It was the kind of generous-spirited performance that made one want to hang around a bit, to let the soloist go at it again in its entirety, perhaps taking a different tack in the next round just for the fun of becoming more deeply acquainted.

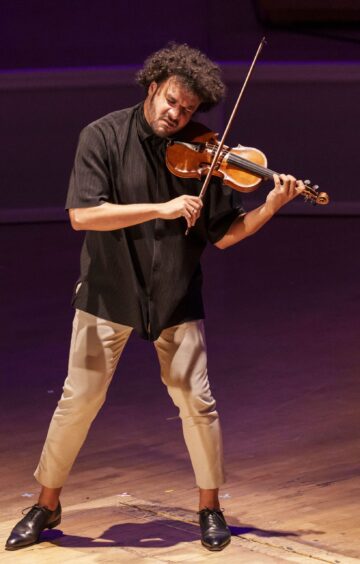

Stewart, on violin in his own concerto “Resonance,” led by Lidiya Yankovskaya with CSO and guest musicians.

The other world premiere, “Resonance,” was by Stewart himself, the first movement of a yet-unfinished three-movement violin concerto. It’s the early result of a MusicNOW commission that Stewart says he envisions as a way of paying homage to his own cultural inspirations.

Specifically mentioned are the 20th-century Hungarian avant-gardist György Ligeti, whose eerie sound world is perhaps best known to mass audiences for its impact in Stanley Kubrick’s film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Stewart’s piece gives a shout-out as well to the flamboyantly virtuosic violin techniques of Wieniawski and the sound worlds of Shostakovich, contemporary jazz and minimalist grooves.

Most evident in my first listening was the impression that Stewart’s “Resonance” is a thing still very much in the midst of creation, with delicate, ghostly effects and sudden fits of turbulence that hint at what may be in store from movements yet to come. In fact, its treatment seemed of a piece with two other works by Stewart on the concert, both emerging after the death of his mother ‒ “Embrace” and “of Love.” All three pieces are steeped in wonder and sadness, with sometimes jagged, raw, tumultuous intrusions of the sort one associates with Shostakovich.

Stewart performed ‘”Embrace” with, from left, violinist Yuan-Qing Yu, violist Danny Lai, bass Robert Kassinger and cellist Chris Wild. The homage to Stewart’s mother used her recorded voice.

CSO performers at these concerts were a typical mix of CSO stalwarts persistently interested in music’s cutting edge ‒ among them percussionist Cynthia Yeh, violinists Yuan-Qing Yu and Nancy Park, violist Danny Lai, and bass Robert Kassinger ‒ along with a few Chicago-based free-lancers known for their kindred passions. These notable locals include clarinetist Susan Warner, pianist Daniel Schlosberg, harpist Janna Young, cellist Chris Wild and the continually impressive Russian-American conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya, 37, who received early career assistance from the Solti Foundation.

Guest conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya frequently explores new works with the CSO musicians at MusicNOW.

Yankovskaya is just right for this MusicNOW assignment, having conducted more than 40 world premieres already, several in her time as music director of Chicago Opera Theater. No surprise that her career is off and running, with upcoming debuts at European opera houses and half a dozen American orchestras.

Much of the success in new music concerts depends on getting the mix right. The inclusion of another composer who straddles these jazz and classical worlds, Tyshawn Sorey, was a shrewd move by Montgomery. Sorey’s 2018 “For Fred Lerdahl” is a shout-out to the respected Columbia University composer-teacher who implored Sorey to honor the reality that his tendency toward improvisation was fundamental in his DNA.

Given the nostalgic interplay of past and present in this concert, the performance of Stewart’s world premiere concerto “Resonance,” though incomplete, seemed to work, somehow, in its way. What we were given showed Stewart to be musing at the fiddle in a brooding, raw, often introspective and intimate vein. The work holds great promise, and I was glad to hear it. Even so, one hopes that complete performances of fulfilled MusicNOW commissions remain the rule at Chicago Symphony events of this caliber.